We’re halfway through Unit 42’s LabyREnth Capture the Flag (CTF) competition, and things are getting interesting. Malware reverse engineers and threat experts across the world are testing their technical skills in binaries, threat intelligence, programming, and more. Armor has been acquired, tears have been shed, cows have been spotted... Plus, puppies!

Have you escaped the LabyREnth yet?

We know many of you are still in the LabyREnth building security skills and solving challenges. Because we don’t want to leave you trapped in the maze, the LabyREnth creators put together a video and several writeups with some of their best tips, tricks, and clues for solving their security challenges. Check them out below.

All monetary prizes have been claimed, but you can still win electronics and challenge coins, so we encourage you to keep going. As always, good luck escaping the LabyREnth!

Documents 1 Challenge Hints

By: Jeff White

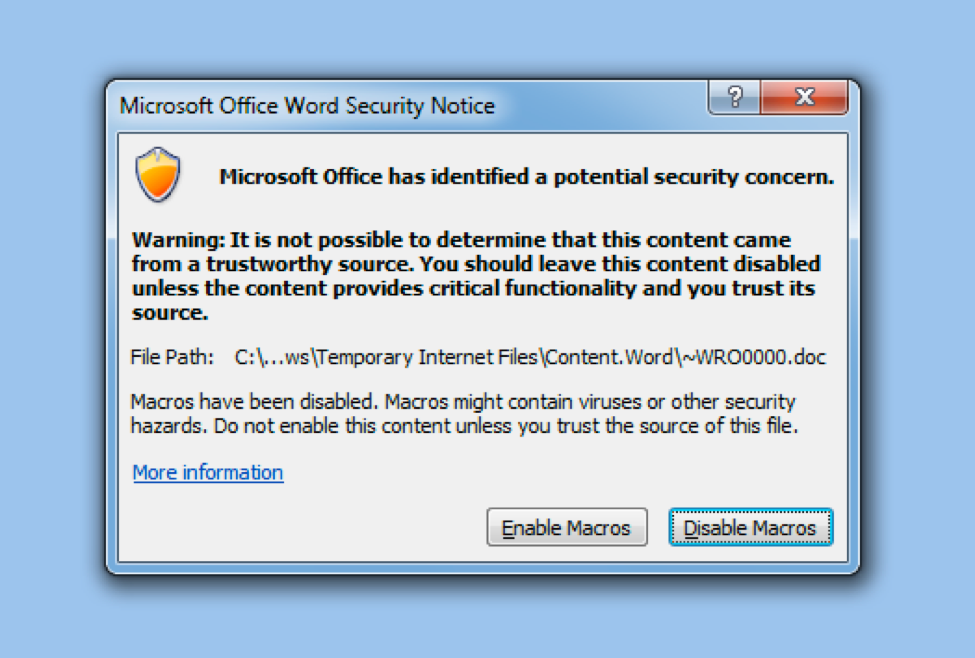

For this challenge, we’re given an RTF file called “find_bbz_challenge_file.rtf” and upon opening it we’re immediately greeted with a prompt to Enable Macros.

Running it we see a message to double click an object with the Firefox icon to “Find BBZ”.

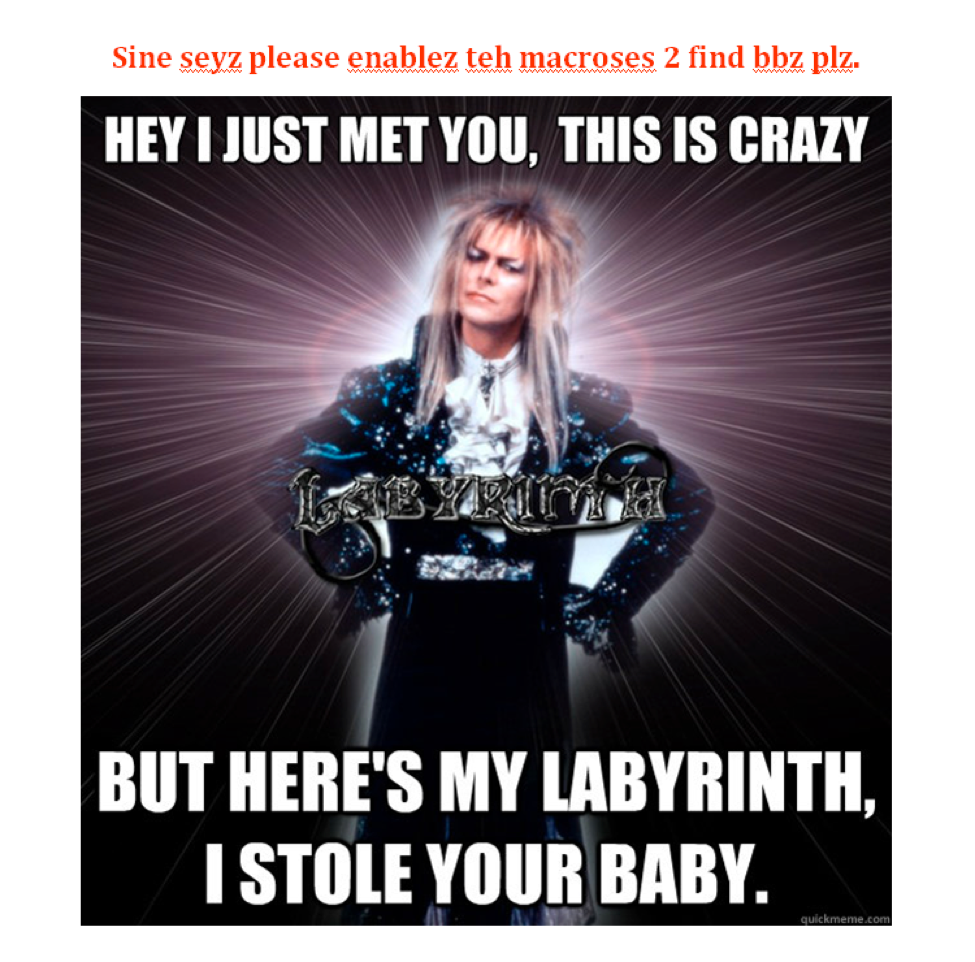

Finally, double clicking this Firefox icon takes us to an image of David Bowie in a new document that is opened.

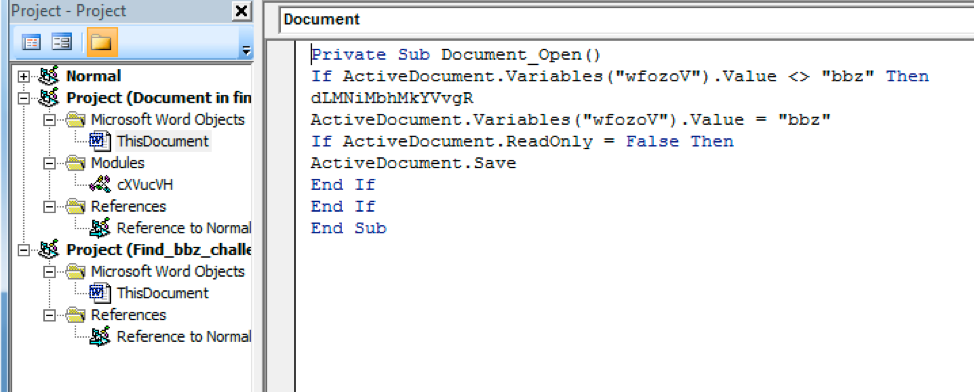

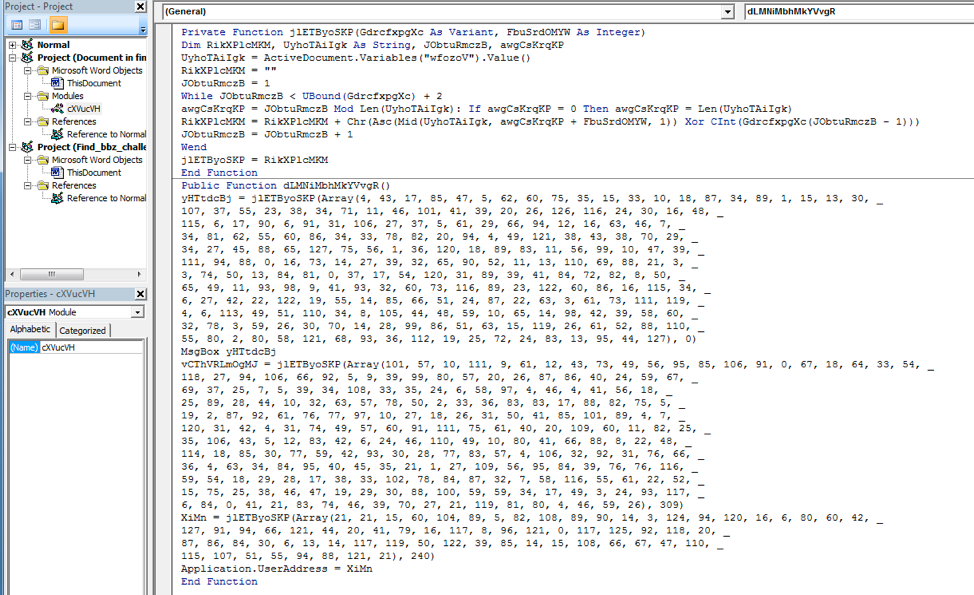

The first thing I like to do when analyzing Word documents like this is to dig into the Macro source and try to understand what’s happening under the hood. I’ll focus on the “Document_Open()” function and follow the logic and debug the code.

Opening up the Visual Basic Editor we see the function under “ThisDocument” and it immediately does a check for the value of variable “wfozoV”; if it does not equal “bbz” then it launches a function “dLMNiMbhMkYVvgR”.

Looking at this function shows some variables being set to the returned result of a call to “jlETByoSKP” with an array of integers and another integer.

This second function appears to be a decoding routine and has familiar operations such as XOR and MOD.

Also of note is the MsgBox function right below the first variable that gets set. Typically, in CTF’s, a MsgBox is used to display the key or other pertinent messages so this is a good place to pause the debugger and see what’s happening.

In the Locals window, you can see the decoded message. Given this, you should be able to decode the rest of the messages and take down the first level Documents challenge!

Binaries 1 Challenge Hints

By: Tyler Halfpop

We are given the following 3 files for this challenge. Two of the files come up as data using the file command and look like they might be compressed or encrypted in a hex editor. One of the files is a PE executable. This is where you might want to start your analysis.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

MyFirstMalware.exe: PE32 executable (console) Intel 80386, for MS Windows config.jpg: data notdroids.jpg: data 7875563cd66e948ff2356ebf9b5e33dbd579ccffafbea82b40cb14ae5f772252 MyFirstMalware.exe 5921f38aa15eaeb3188438ebf85d3cb29e4b9a74b21fa9dadc110dfdf8a410da config.jpg fcb8ce15333bf305b9025edfcfe6b5864ddc941b03d68fb4c54ca722b9f44d12 notdroids.jpg |

If you check the strings for MyFirstMalware.exe you will find the correct location to place the other two files in your virtual machine.

|

1 2 |

C:\notdroids.jpg C:\config.jpg |

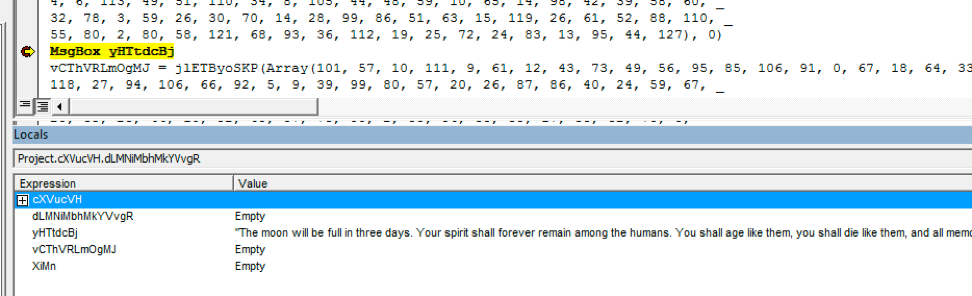

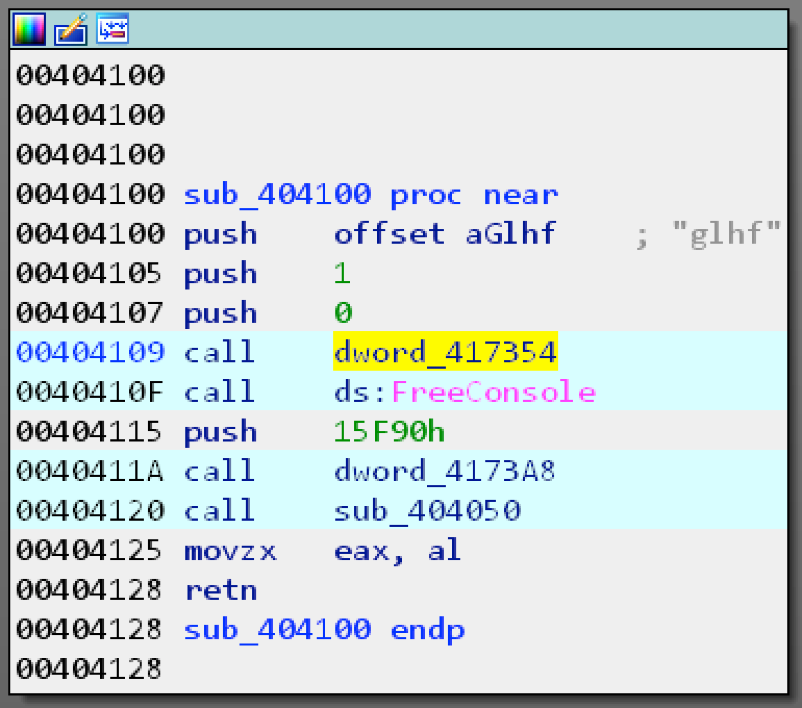

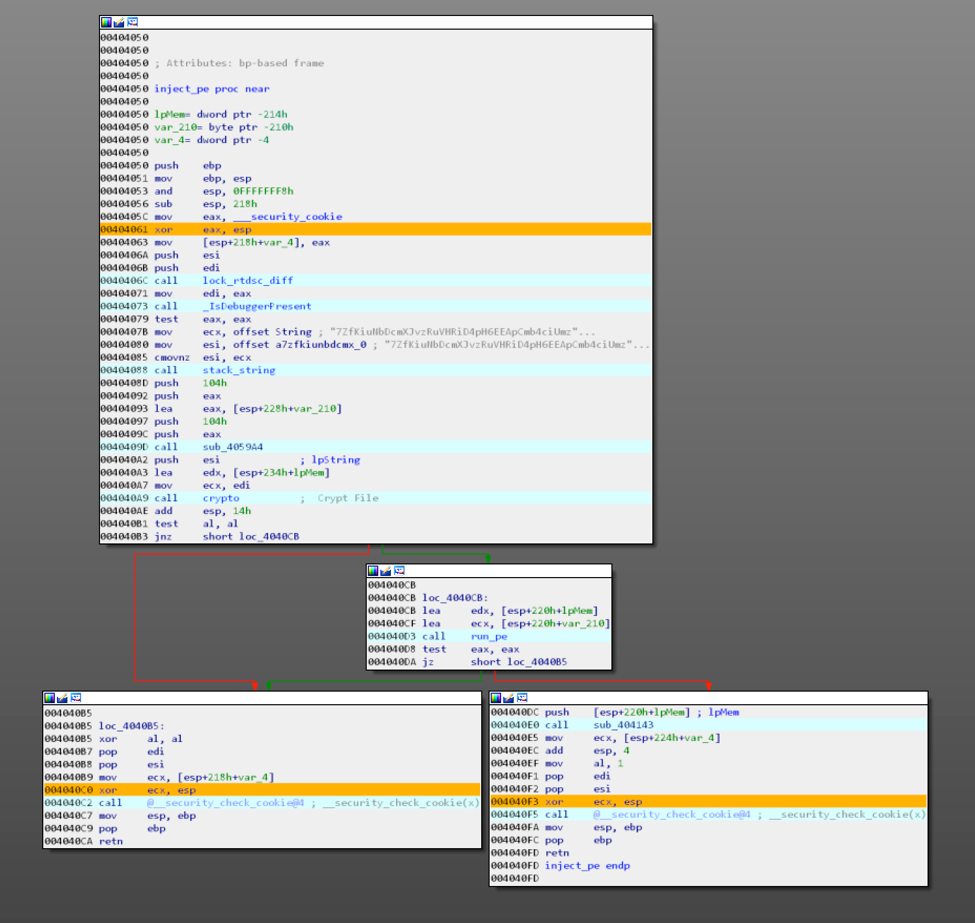

If you open MyFirstMalware.exe in a disassembler like IDA and find the main method pictured below you can see that a few of the calls are dynamically resolved.

Figure 1 main method

The simplest method to determine what these calls are is to use a debugger and step through the program to see what is being called. Most of the APIs in this challenge are resolved dynamically like this. This is a common technique that malware authors use to try to make their code more difficult to analyze.

You will need to do something about the sleep call or you will be waiting for a long time. The simplest method is just to change the parameter pushed to sleep to 1 and then nop out (0x90) the remaining bytes.

Figure 2 Renamed functions and patched sleep call

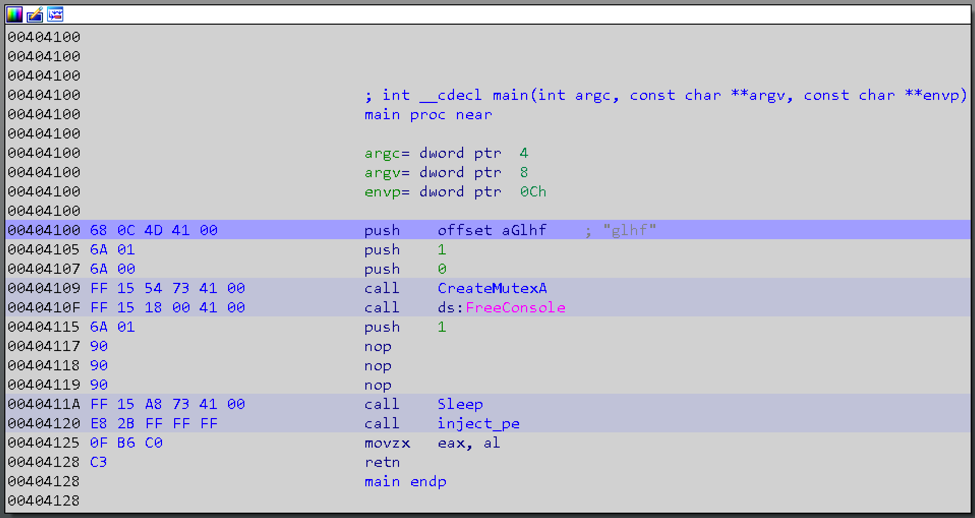

Next you will encounter a few anti-analysis techniques that will set variables used for the file decryption. You need to pass the checks correctly in order to get the correct file to decrypt and the correct password. After the checks a string is built with the name of an executable, followed by a function that handles the file decryption.

Figure 2 Disassembly Anti-Checks and Main Flow

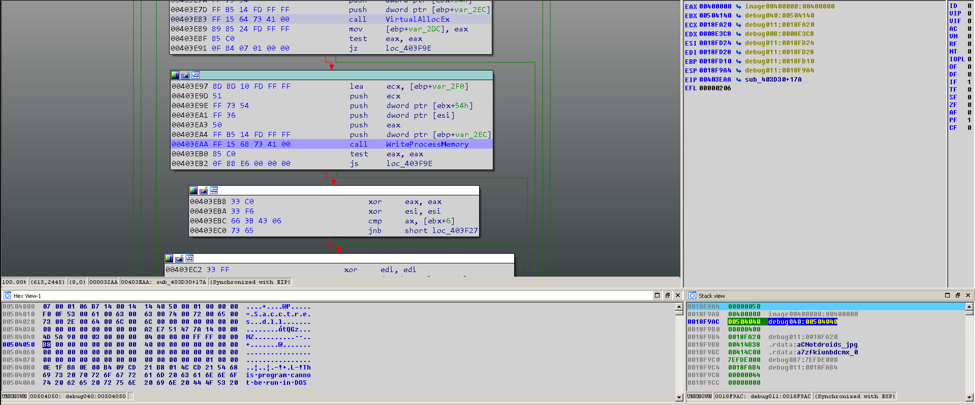

After you are able to pass the checks correctly and decrypt the correct file it is injected into another process. You will need to dump this executable in order to analyze it. Set a breakpoint on WriteProcessMemory when you find it and then dump the memory pointed to by the third argument on the stack.

Figure 3 WriteProcessMemory breakpoint showing MZ header

You can then start analyzing the dumped binary, which employs similar tricks. You should be able to apply the same strategies used on the first binary to find the key.

Threat 2 Challenge Hints

By: Jeff White

If you played the CTF last year you’ll immediately be familiar with this challenge. We’re given a folder of 50+ malicious files and are tasked with creating a YARA rule to find a common, specific, function across the set. This is a common practice when analyzing threats and it allows you to find related samples which can then expand your overall knowledge of a given family.

The directions.txt file that comes with the samples gives us more insight into what’s required. Specifically, our rule will need to match the following syntax and will need to include 308 wildcard’s for a total of 298 byte matching hex-rule.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

rule yara_challenge { strings: $yara_challenge = { de ad b? ef ?? ??} condition: all of them } |

Typically, what I do in these scenarios is start with the smallest file possible as it must contain the function we’re interested in and will have less noise, then I’ll choose a larger file that will have more noise but should make finding similarities easier. For this example, I’ll use the below samples if you want to follow along.

Small (94KB) - 7f63e65ab460ff8ad607ede5bedb9573263015ba81824c3896f5416969353dba

Large (394KB) - c99b32b4bd6744311cdb357c8fa2210de6b79873f104a8f6268c2e60c606d330

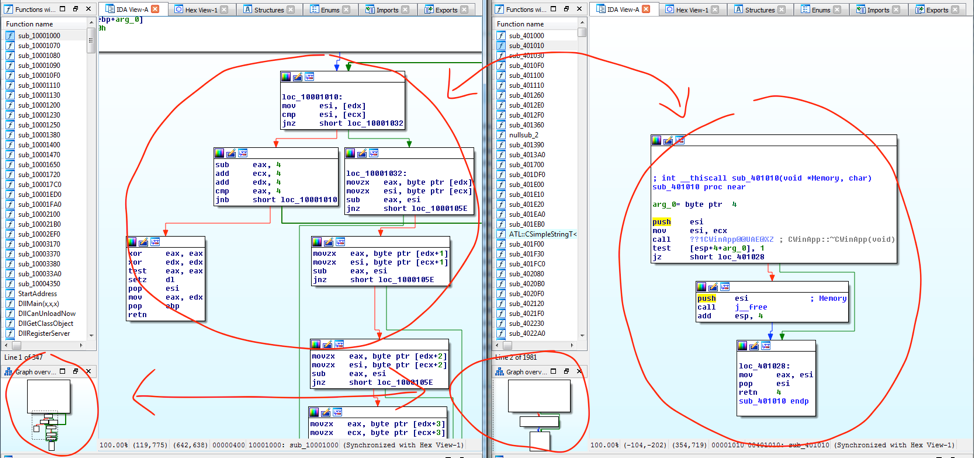

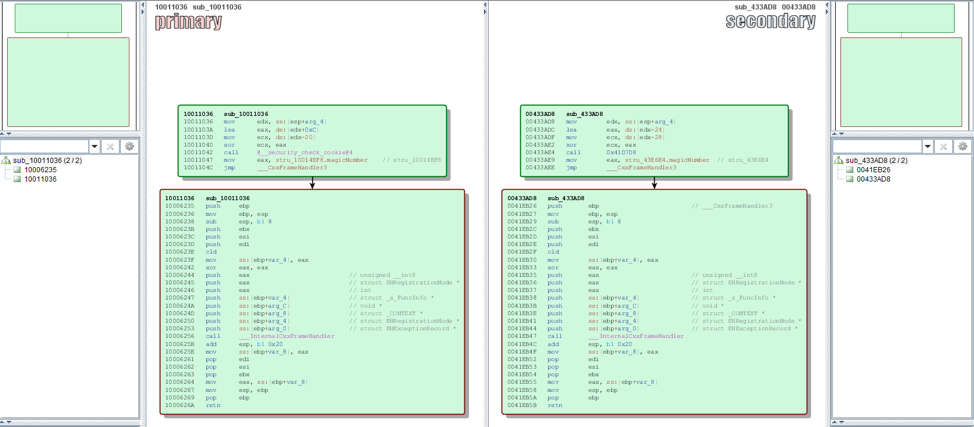

There are a few methods to approach this problem and the most basic is a simple visual comparison inside a disassembler like IDA. You can compare the basic blocks and graph overview one-by-one to see if anything visually matches.

Based on the image above, you can see neither of these functions match. At this point you can go down the list until something stands out but this can be extremely time consuming and prone to simple mistakes.

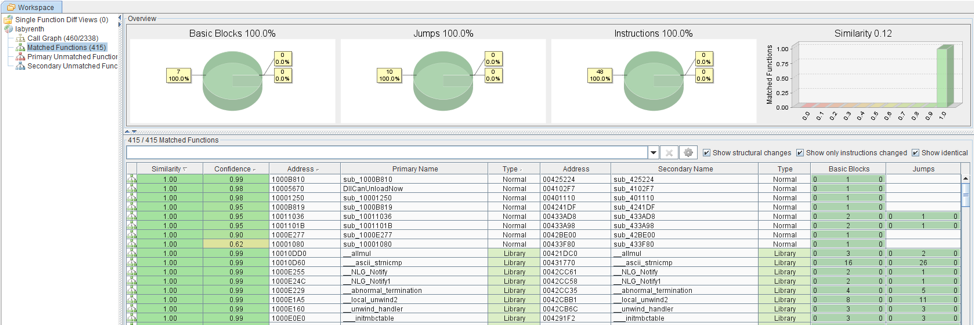

Another method for comparison is to use a tool like BinDiff and take advantage of its built-in “Similarity” scoring system to see if any basic blocks match.

You can sort the results by Similarity and Confidence to focus in on blocks that appear to be shared between samples. This helps reduce the noise reduce the overall amount of time required.

If you open one of the high Similarity/Confidence blocks up, you’ll see a visual comparison similar to what we saw in IDA.

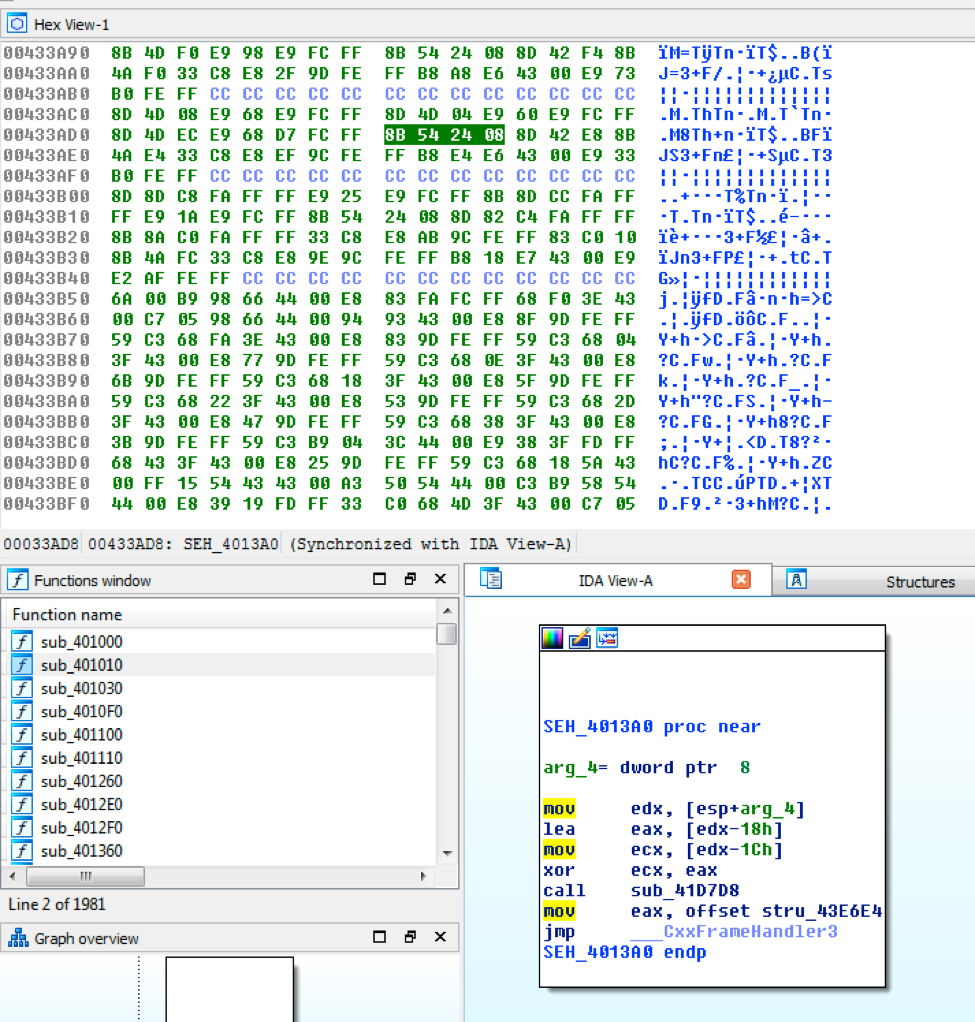

In the above image, you can see two functions that are an exact match. If this was the correct size and what we’re after, we can grab the underlying hex bytes which make up the instructions and values. Looking at the hex in IDA we can build a rule based on this data.

Where the MOV instruction is highlighted as “8B 54 24 08”. Our resulting YARA rule, for this one instruction, would then look like the below.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

rule yara_challenge { strings: $yara_challenge = { 8B 54 24 08 } condition: all of them } |

Rinse and repeat for the entire function until you have the rule. Keep in mind that the function size is 298 bytes so it’s fairly large.

The wildcards come into play when you consider things like offsets or values used by the instructions. In our above example, “MOV EDX, [esp+arg_4]” exists in one sample but what if in another sample it’s arg_B? In that case, the instruction could be the same but we need to account for this delta with a wildcard in YARA so that it still matches between the two.

Below is the same rule but with a wildcard that specifies ANY value here, assuming the rest match, will result in a match.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

rule yara_challenge { strings: $yara_challenge = { 8B 54 24 0? } condition: all of them } |

With 308 wildcards, you can bet the function you’re looking for is going to have a lot of different values!

Mobile 3 Challenge Hints

By: Tyler Halfpop

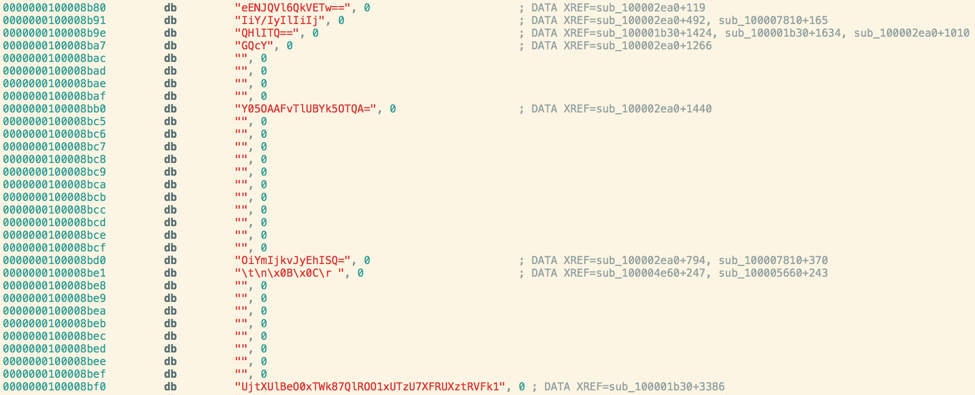

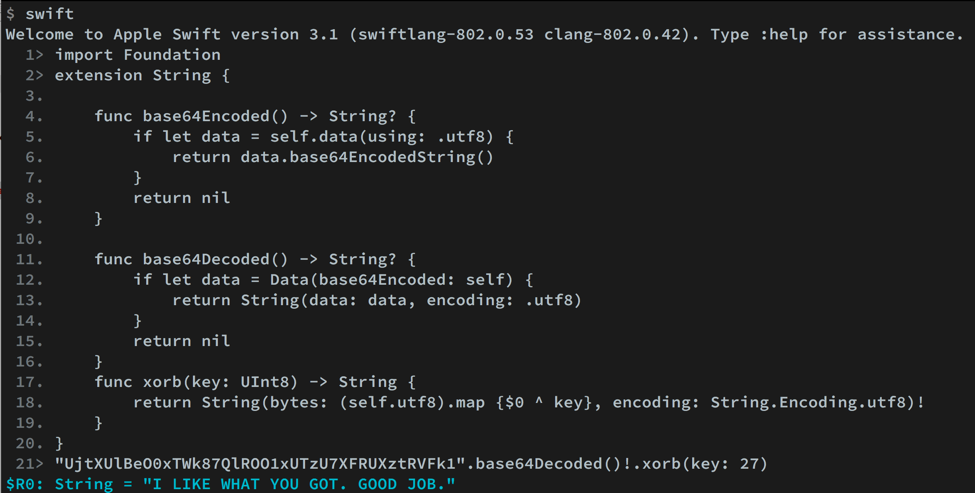

This challenge is an iOS app that was written in Swift. If you look at the strings you might notice that there are what looks like some base64 encoded strings.

The strings are base64 encoded and xor encoded with different keys. We can use the Swift interpreter and these functions below to decode the strings. After we decode the strings we can see what looks like a device name, some GPS coordinates, a device type, a decimal, a good job message, and a failure message. You need to make sure you have the correct values for the environment checks in order to decrypt the key properly.

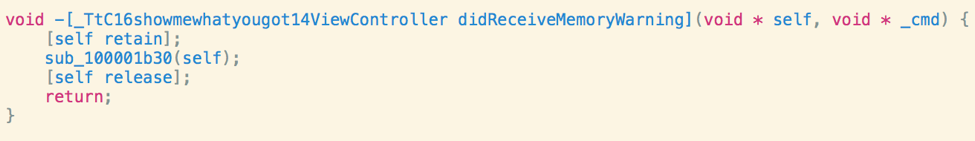

If we look at the cross references for the example decoded good job message displayed above. We can see that the function that references the string is called from a memory warning. We can also see some functions related to AES encryption and crc32 algorithm.

Programming 3 Challenge Hints

By: Richard Wartell

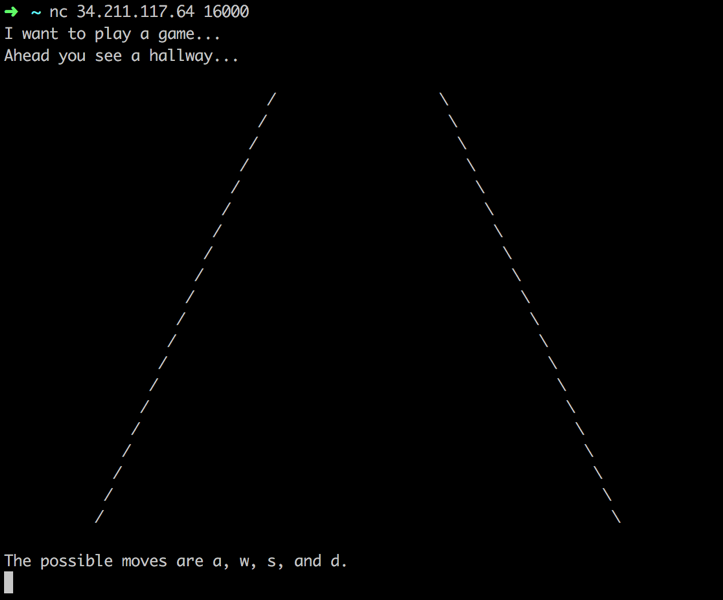

For the third challenge of the programming track, we’re given an IP address and port, as well as a hint that states: “The transition from first person to third person is real hard, especially when the game's a cheater...”. This hint refers to the first challenge from the programming track, which is a third person maze. This challenge is a first person maze in ascii art that you must solve in order to progress. When we connect to the challenge we see this:

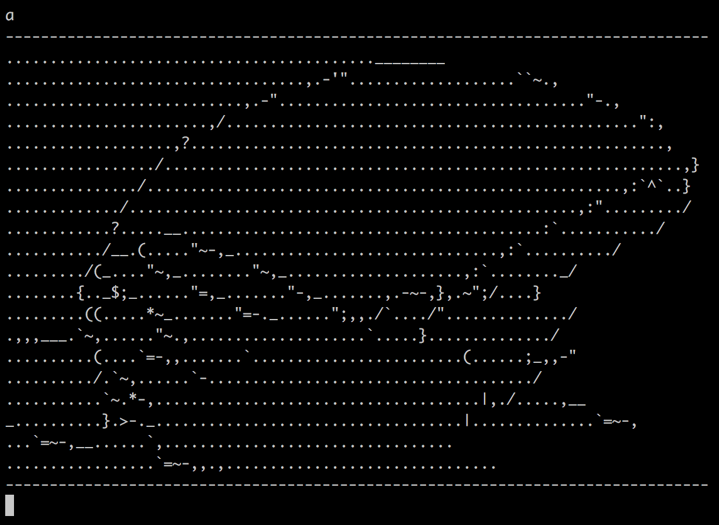

The challenge appears to take 4 possible moves: w for move forward, a for turn left, d for turn right, and s for move backwards. Now if we start moving through the maze a little bit, we start to realize that this game cheats. After walking for a while, we keep running into a wall.

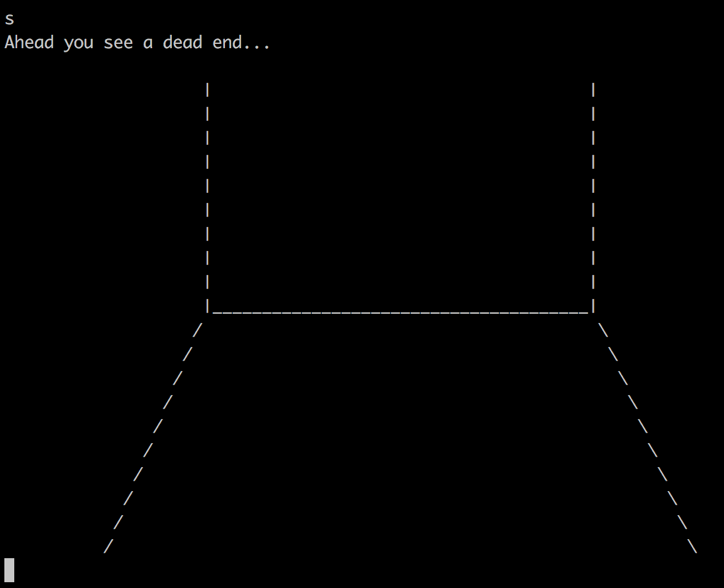

Disconnecting from the challenge and reconnecting allows us to start over, however this keeps happening. After walking for a while, we keep ending up at a dead end like the one below, as if the challenge is creating new walls as you play.

The challenge here is to figure out how the game cheats, as it must be predictable in order to be solvable, and then get to the end of the maze where the key awaits.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42