Executive Summary

Seasoned attackers will tell you that persistence is an important part of any successful hacking campaign. Persistence allows attackers to maintain continuous control of their captured servers. Whether they are hijacking resources, exfiltrating data or using their target machines as proxies, attackers always face the risk of having their treasured vulnerabilities patched and sealed, eliminating their way in. The shift from traditional computing to technologies like containers and serverless has made persistence harder to obtain, thanks to the transient nature and strong isolation mechanisms of these technologies.

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from these attacks by Prisma Cloud, which successfully detects and mitigates vulnerabilities as well as using Prisma Cloud Compute’s extensive audits and runtime defense features to catch adversaries attempting to obtain persistence on their machines.

Containers and Serverless Limit Attackers

Mitigating vulnerabilities is often the main focus of container and serverless security audits. Security auditors scan for all known vulnerabilities in running containers and in images to prevent any flaw that malicious actors could exploit. Yet even the most careful and pedantic security review cannot detect zero-day vulnerabilities that some sophisticated adversaries might be lucky to own.

For that reason, successful security models include multiple layers of defense. Attackers who manage to gain an initial foothold are hindered by runtime protections, limited privileges and confined access to resources such as computing, memory and networking. What is the adversary able to achieve upon successfully exploiting a vulnerability? In what ways could attackers exfiltrate data or impact services?

This is where containerized environments and serverless have an inherent benefit over traditional computing. Containers are limited in their function and privilege by design. They are temporary and disposable, and their resources can be easily controlled. Serverless functions are even further limited in their scope. They are only executed on call and are often designed with limited privileges and access to resources.

Persistence, a Challenge

Certainly, attackers may have a hard time leveraging breached containers or serverless functions to their use. But obtaining persistence over these instances may prove to be an even larger challenge.

Let us briefly discuss the idea of persistence. Through successful exploitation, attackers may gain temporary access to a target machine and use it for their benefit. They could run cryptominers or extract data. But soon enough, the vulnerability that let them in may be patched. In order to retain control of the machine – and their payload – attackers must find a way to base their presence in that machine. Persistence can be achieved through simple, passive methods, such as editing configurations, or by more active methods such as installing or modifying binaries and libraries. The attackers may have their code run on the machine periodically, at every boot or on their demand, thus providing them access to the machine even if their initial entry method is mitigated. This piece of code or configuration that lets the attackers back in is called a backdoor, and they may control it through their own machine or through a command and control (C2) server connected to a horde of infected machines.

Now let’s take a look at containers. As a rule of thumb, containers are meant to be short-lived. Many containers have a lifespan from a few hours to a couple of days. Even in the rare cases where containers are being used for indefinite periods, such as to replace permanent virtual machines (VMs), they are disposed of and relaunched every time there is an update or change to the container image. Container orchestrators such as Kubernetes rely on that concept to the core, spinning up containers automatically on a large scale.

Container Persistence

With containers being ephemeral, the traditional methods that attackers use to obtain persistence are only partially effective. Methods such as installing cron jobs, modifying binaries or making other changes to files would only last until the container is shut down.

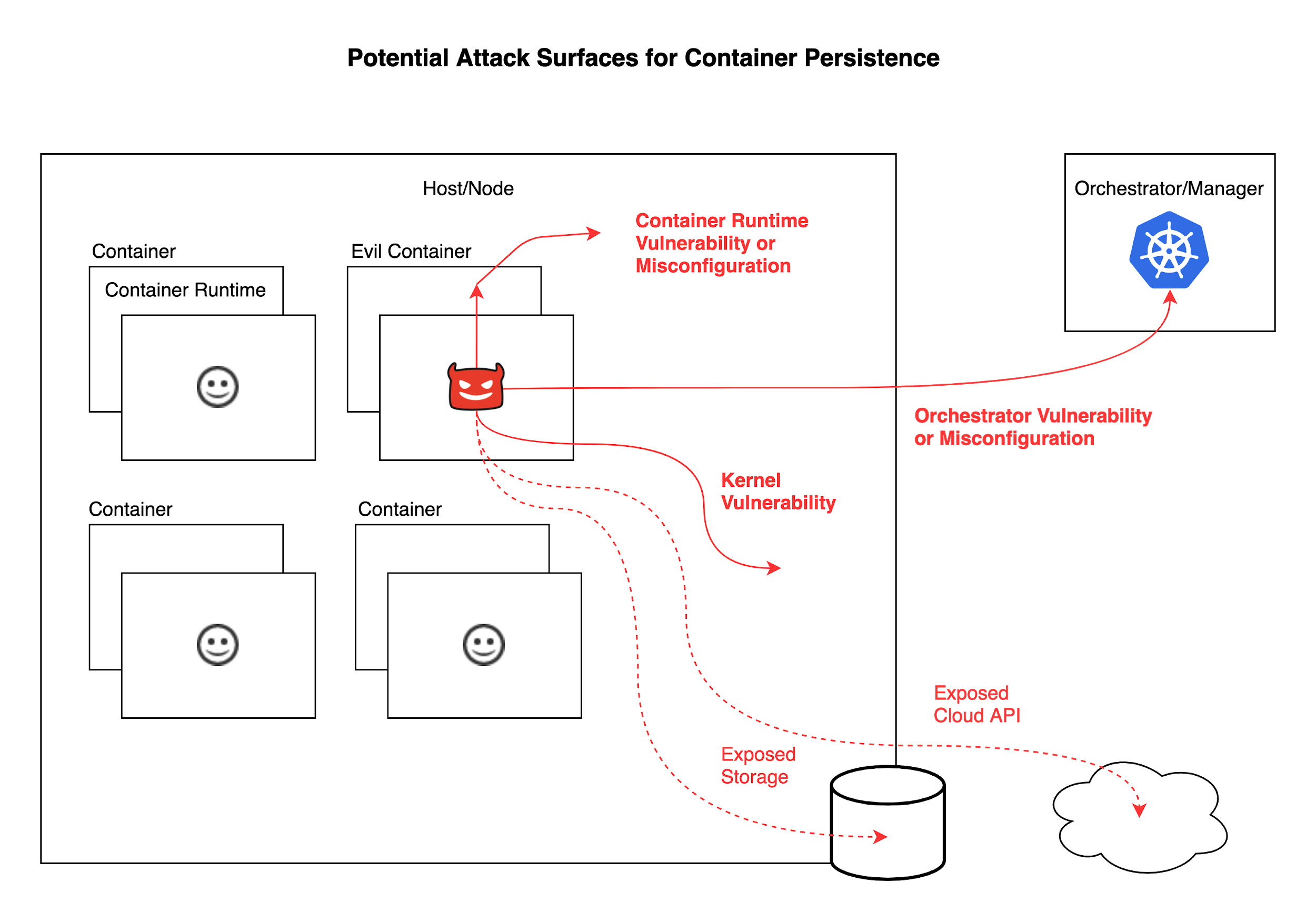

Creative attackers might try to find non-standard ways to persist in containers by exploiting the architecture specific applications are built in. For example, if the container does anything like run code from persistent storage (such as volumes or bind mounts) or a database, the attacker can hook on that functionality and install their backdoor in these external devices. Misconfigurations such as excessive container capabilities, or exposed credentials and API keys are also likely to be exploited by the attackers in search of persistence.

Nevertheless, how can attackers obtain persistence in standard containers when security is configured by the book? To escape the boundaries of the container environment, they must exploit vulnerabilities in its heart. That is, they must exploit either the operating system (OS) kernel, the container runtime or the orchestrator.

It is possible that established and well-funded attackers will have a zero-day vulnerability that can help them accomplish this. But it is not always needed. If their target runs outdated software, they could be successful with known past vulnerabilities that allow escaping a container. There are numerous publicly known vulnerabilities in the Linux kernel and kernel modules that allow attackers to execute code in the kernel scope, or otherwise escape a container’s limitations.

Vulnerabilities in the container implementation, such as in Docker or runC, could also let the attacker escape and obtain persistence on the container host. One famous example from recent times is CVE-2019-5736, which would allow attackers to escape a container when the exec command is run. Other vulnerabilities discovered in the past would allow full escape with zero user interaction once an attacker landed in a container. One example is the recently disclosed Windows container escape.

Serverless Persistence

Despite their similarities to containers, serverless functions expose fewer attack vectors through which they can be compromised. Serverless functions run in a controlled environment, provided by the serverless platform. The scope of each function is limited to parsing its input and completing its action. Everything else from networking to storage is handled by the cloud provider. In order to attack a serverless function when lacking any misconfigurations to exploit or a vulnerability in the cloud provider itself, an attacker must find either a flaw in the function code or a vulnerability in any package used by that code.

For example, a function running a Python handler to parse YAML data would be vulnerable to flaws in its YAML parsing package and its dependencies. The attacker could invoke the function with data that triggers the exploit and gain control of that function’s execution environment.

The environment exposed to a successful attacker is rather limited. The actual privileges and restrictions the attacker would encounter depend both on the nature of the vulnerability and on the architecture of the serverless platform. But one thing that is universal for serverless functions is that their lifespan is short.

Serverless functions are expected to run for a few seconds, complete their objective and diminish, until a new instance starts up when called for again. Not only that, but the runtime environment in which the serverless functions run is also temporary. The Amazon Web Services (AWS) Lambda runtime, for instance, lasts approximately 15 minutes when left untriggered.

In a recent article on AWS Lambda persistence, Unit 42 researcher Yuval Avrahami demonstrated that an attacker could persist in the serverless environment between function invocations. An attacker could successfully control the handler results and leak the data from multiple executions.

In order to obtain real persistence, however, the attacker would have to prevent the AWS framework from taking down the instance being controlled. This can be achieved by continuously delivering requests to the function, a process sometimes referred to as keeping the function “warm.”

By invoking the function periodically in a pattern, the attacker would likely increase the chance of the compromised function being detected. Therefore, sophisticated attackers would have to come up with additional methods to obfuscate their intent. Even so, such a scenario is not far-fetched.

Conclusion

Both containers and serverless functions limit malicious actors from achieving persistence, each with its own constraints. Successful attackers would either have to settle for temporary execution, or find ways to break out of the container or function sandbox to get real persistence. While the same constraints can be applied to traditional VMs as well, it is likely that they are not designed to be ephemeral like containers or serverless functions.

From a defensive point of view, this makes both containers and serverless convenient for continuous security. Breached containers or functions can be easily detected and disposed of, while new patched code could rapidly be pushed to retain functionality.

Palo Alto Networks customers using Prisma Cloud can successfully detect and mitigate vulnerabilities and rely on Prisma Cloud Compute’s extensive audits and runtime defense features to catch adversaries attempting to obtain persistence on their machines.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42