In Part 5 of our IDAPython blog series, we used IDAPython to extract embedded executables from malicious samples. For this sixth installment, I’d like to discuss using IDA in a very automated way. Specifically, let's address how we’re going to load files into IDA without spawning a GUI, automatically run an IDAPython script, and extract the results. Using this technique, we’ll be able to process many samples very quickly without needing to manually open each file in a new instance of IDA and run the IDAPython script.

Many may be surprised to learn that IDA can be executed purely on the command-line without spawning a GUI. In order to do so, the user must run the IDA executable with the ‘-A’ switch. This particular switch will instruct IDA to run in autonomous mode, ensuring that no windows or dialog boxes are presented to the user.

The following command-line examples demonstrate this technique being used in both OSX and Microsoft Windows . In these examples, the ‘-c’ switch generates a new IDB file, even in the event one already exists. Additionally, the ‘-S’ switch specifies the IDAPython script that will be run upon execution. We’ll be using these switches later on in the post.

|

1 2 3 |

"/Applications/IDA Pro 6.9/idaq.app/Contents/MacOS/idaq" -c -A -S/tmp/script.py file.exe "C:\Program Files\IDA 6.9\idaq.exe" -c -A -SC:\script.py C:\file.exe |

The Scenario

For this example, I’m going to use the Cmstar malware family, previously discussed by Unit 42. For those unfamiliar with this malware family, it is a downloader that will transfer a file hosted at a specific URL over HTTP(S) and execute it on the victim’s system. The URL in question can be de-obfuscated using the following routine.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

def decode(data): out = "" c = 0 for d in data: out += chr(ord(d) - c - 10) c += 1 return out |

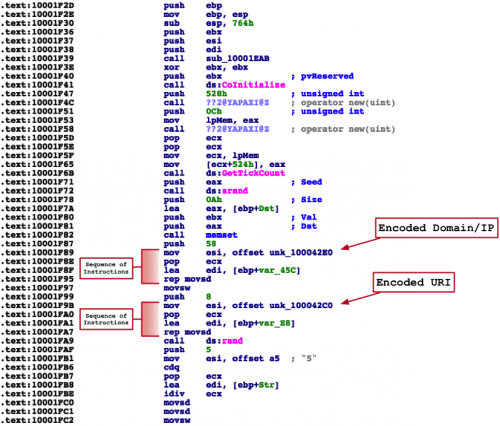

Knowing this, our next task is to identify where this data resides within a Cmstar sample. Correlating across a few samples, we conclude that two encrypted strings are being stored into a variable using calls to memcpy. One of the strings contains the domain or IP address that the malware will connect to, while the other contains the URI.

We also notice that the same sequence of instructions are executed when this memcpy instruction takes place:

mov esi, [offset]

pop ecx

lea edi, [variable]

rep movsd

Figure 1 Function containing encoded strings in Cmstar

Armed with this information, we can attempt to identify this sequence of instructions using IDAPython. To do so, we’ll iterate through every function IDA identifies, and proceed to ignore any functions marked as a jump function or belonging to a known library. The remaining functions will then be iterated through using a sliding window where we’ll inspect four instructions at a time, seeking the markers previously identified to determine if there are any matches:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 |

import idc, idautils for func in idautils.Functions(): flags = idc.GetFunctionFlags(func) # Ignore THUNK (jump function) or library functons if flags & FUNC_LIB or flags & FUNC_THUNK: continue dism_addr = list(idautils.FuncItems(func)) for c in range(len(dism_addr)): try: # Look at four instructions at a time v1 = dism_addr[c] v2 = dism_addr[c+1] v3 = dism_addr[c+2] v4 = dism_addr[c+3] # Look for known markers indicating we're seeing the encoded strings # being copied to a variable. if idc.GetMnem(v1) == 'mov' and idc.GetOpnd(v1, 0) == 'esi': if idc.GetMnem(v2) == 'pop' and idc.GetOpnd(v2, 0) == 'ecx': if idc.GetMnem(v3) == 'lea' and idc.GetOpnd(v3, 0) == 'edi': if idc.GetDisasm(v4) == 'rep movsd': print "[*] Found instruction starting at 0x{address:x}".format(address=v1) except IndexError: # Sliding window went past the end of the function None |

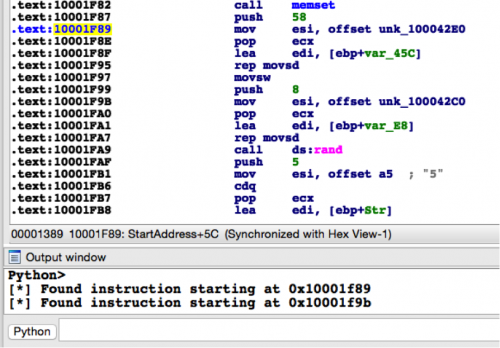

In the above example, I’m simply printing out a debug string if I find any matches. Running this code against the sample with an MD5 hash of 4BEFA0F5B3F981E498ACD676EB352D45 in IDA, we get the following output. As we can see below, we’ve successfully identified the addresses of both obfuscated strings.

Figure 2 Running script against Cmstar sample

At this point, we can take the offsets we’ve identified and extract the strings to which they point. These strings can then be decoded using the previously defined decode() function.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 |

addr = idc.GetOperandValue(v1, 1) data = "" while Byte(addr) != 0x0: data += chr(Byte(addr)) addr += 1 decoded = decode(data) addr = idc.GetOperandValue(v1, 1) |

Putting this all together, we come up with the following script:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 |

import idautils, idc, idaapi def decode(data): out = "" c = 0 for d in data: out += chr(ord(d) - c - 10) c += 1 return out # Wait for auto-analysis to finish before running script idaapi.autoWait() url = "" for func in idautils.Functions(): flags = idc.GetFunctionFlags(func) # Ignore THUNK (jump function) or library functons if flags & FUNC_LIB or flags & FUNC_THUNK: continue dism_addr = list(idautils.FuncItems(func)) for c in range(len(dism_addr)): try: # Look at four instructions at a time v1 = dism_addr[c] v2 = dism_addr[c+1] v3 = dism_addr[c+2] v4 = dism_addr[c+3] # Look for known markers indicating we're seeing the encoded strings # being copied to a variable. if idc.GetMnem(v1) == 'mov' and idc.GetOpnd(v1, 0) == 'esi': if idc.GetMnem(v2) == 'pop' and idc.GetOpnd(v2, 0) == 'ecx': if idc.GetMnem(v3) == 'lea' and idc.GetOpnd(v3, 0) == 'edi': if idc.GetDisasm(v4) == 'rep movsd': addr = idc.GetOperandValue(v1, 1) data = "" while Byte(addr) != 0x0: data += chr(Byte(addr)) addr += 1 decoded = decode(data) url += decoded except IndexError: # Sliding window went past the end of the function None current_file = idaapi.get_root_filename() f = open("/tmp/output.txt", 'ab') if url != "": f.write("[+] {0} : {1}\n".format(current_file, ''.join(url))) f.close() idc.Exit(0) |

At this stage, we can use the automation technique of running IDA in non-GUI mode and use the above script. This will allow us to run this script against a number of samples without the need for user interaction. We’ll run the script on our OSX machine as follows:

for x in ls; do /Applications/IDA\ Pro\ 6.9/idaq.app/Contents/MacOS/idaq -c -A -S/tmp/script.py $x; done

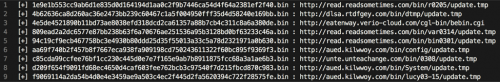

After a few minutes, we’re treated to the following within /tmp/output.txt, which is where we instructed our script to store results.

Figure 3 Output of /tmp/output.txt

Conclusion

By leveraging both the power of IDAPython, along with IDA’s command-line switches, we’ve successfully automated the extraction of the download location of a number of Cmstar samples. This technique can easily be applied to a larger number of samples, allowing us to execute IDAPython actions without needing to manually open each file in IDA. For those readers who were not aware of this IDA capability, I implore you to investigate it, as it can not only save you time, but also make things much easier when working with a large number of files.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42