Malware writers have always sought to develop feature-rich, easy to use tools that are also somewhat hard to detect via both host- and network-based detection systems. For many years, one of the go-to families of malware used by both less-skilled and advanced actors has been the Poison Ivy (aka PIVY) RAT. Poison Ivy has a convenient graphical user interface (GUI) for managing compromised hosts and provides easy access to a rich suite of post-compromise tools. It is no surprise it’s now being used against pro-democracy organizations and supporters in Hong Kong that have long been a target of advanced attack campaigns.

Despite its simplicity and prevalence, detection rates for both AV and IDS systems has always been surprisingly low for Poison Ivy. Possibly for these reasons, since the mid-2000s threat actors have frequently used Poison Ivy to establish beachheads within target organizations, although this occurs much less frequently today than in years past. Since the last public release of version 2.3.2 in 2008, new variants of the tool have been relatively rare, especially versions which modify the core communication protocols.

Unit 42 observed a new version of Poison Ivy which uses the popular search order hijacking, a/k/a “DLL Sideloading,” technique frequently seen in malware such as PlugX. The Poison Ivy builder has an output format option of either PE file or shellcode, and in this case the backdoor was built as shellcode and then obfuscated to help prevent detection. While analyzing the sample, we also observed a modified network communication protocol which will be discussed in this blog.

In March, Unit 42 observed this new Poison Ivy variant we’ve named SPIVY being deployed via weaponized documents leveraging CVE-2015-2545. All of the decoy document themes involved recent Hong Kong pro-democracy events. In all of the samples we’ve found to date the exploit drops a self-extracting RAR which contains three files:

- exe - a legitimate, signed executable which is used to side-load the malware DLL

- dll - the malware DLL loaded by RasTls.exe, which then loads the Poison Ivy shellcode file

- hlp - the encoded shellcode Poison Ivy backdoor.

Both identified C2 domains are third-levels off of leeh0m[.]org, which was created in late February 2016, less than a month before the attacks.

Figure 1. Malicious RARs and the three files within

In addition to the new variant we discovered, Japan’s Computer Emergency Response Team Coordination Center (JPCERTCC) published a blog last July on a different new variant. That variant is also side-loaded from a legitimate executable and stub DLL, but the shellcode isn’t encoded the same way as SPIVY. JPCERTCC didn’t comment on who was being targeted in their blog, but it is notable that two distinct Poison Ivy variants have recently appeared, several years after the tool largely fell out of common use by advanced actors.

SPIVY Analysis

We believe the samples dropped have a direct connection to older Poison Ivy RATs based off of the behaviors and code reuse present in the shellcode loaded by the samsung.hlp file within the RAR. Once decoded, the shellcode is launched by ssMUIDLL.dll.

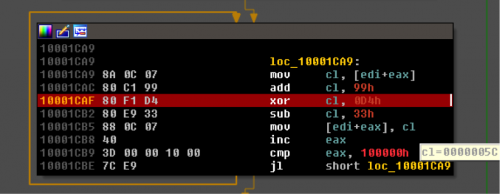

Figure 2. The encoded shellcode is decoded with a single byte addition of 0x99, XOR with 0xD4, then subtract 0x33.

The SPIVY RAT uses the same API call table generation historically used by Poison Ivy. Shown below is a comparison of a PIVY sample from 2008 and our newer SPIVY sample on the right. Both have the exact same API call table function.

Figure 3. PIVY sample from 2008 and SPIVY variant with the same API call table function.

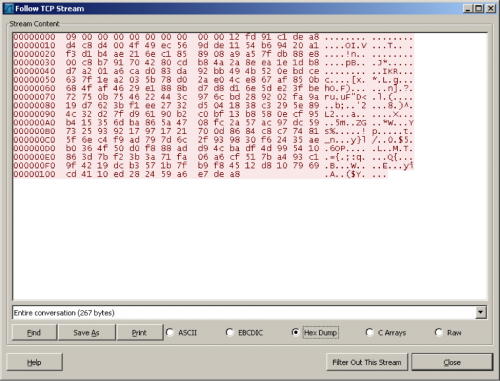

Unlike previous versions of Poison Ivy which utilize a fixed 256 byte challenge-response handshake, this new version generates a payload that has been prepended with anywhere from 1 to 16 bytes of pseudo-random data (plus control bytes), the 1st byte of which gives the length of the padding before the start of the 256 byte handshake. In the example below the first byte (0x09) tells the Poison Ivy controller to ignore the following 9 bytes (which were nulled out below for illustration purposes), plus one more byte which holds the first byte multiplied by 2 ( 0x09 X 2 = 0x12). Two control bytes, plus the 9 random, plus the 256 byte handshake gives us 267 total bytes. The Poison Ivy protocol has been very well documented in previous research by Conix Security and others, and in these samples the remainder of the protocol remains unchanged.

Figure 4. SPIVY’s new challenge-response.

We saw two Poison Ivy configurations with our samples, shown below.

SHA256: 9c6dc1c2ea5b2370b58b0ac11fde8287cd49aee3e089dbdf589cc8d51c1f7a9e

Password: bqesid#@

C2 domain: found.leeh0m[.]org

C2 port: 443

Mutex: 40EM76iR9

ID: 03-18

Group: 03-18

SHA256: 4d38d4ee5b625e09b61a253a52eb29fcf9c506ee9329b3a90a0b3911e59174f2

Password: bqesid#@

C2 domain: sent.leeh0m[.]org

C2 port: 443

Mutex: 40EM76iR9

ID: 03-07

Group: 03-07

Decoy Documents

Decoy documents are a common technique used by many actors to trick victims into believing they have opened legitimate files from spear phishing e-mails. The attacker sends a malicious file which infects the host with malware and then displays a clean document which contains content the victim is expecting to see.

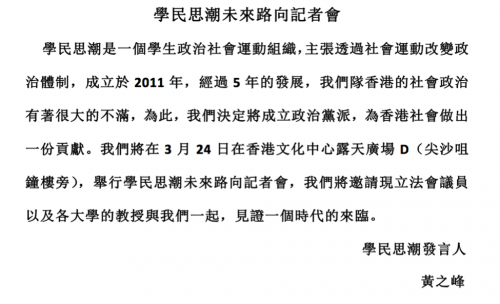

The decoy documents associated with SPIVY are notable because they reference very specific recent events and organizations not widely publicized or known outside of the Hong Kong region and the pro-democracy movement. In addition, all appear to be legitimate invitations to actual events in Hong Kong. One of the decoys purports to be from Joshua Wong, announcing a press conference about ending the Scholarism group to start a progressive democratic political party, Demosistō, in March 2016. Joshua Wong is a well known Hong Kong activist who was one of the founders of the group and is the current Secretary-General for the political party. Scholarism centered around concerns for the Hong Kong’s Department of Education adding a mandatory course for all secondary-school students for “moral and national education”. Scholarism was successful in stopping the course and its members desired to shift into a political party to effect further change.

Figure 5. Invitation to press conference about disbanding Scholarism and establishing a political party.

Another decoy concerns the Mong Kok riot that took place February 8, 2016, the first day of the Lunar New Year. It purports to be from the Justice & Peace Commission of the Hong Kong Catholic Diocese and calls for the government to establish an independent commission to investigate the cause of the riots and for parishes to establish booths throughout April staffed with church members advertising this. The riots were officially written off as being caused by a crackdown on unlicensed street vendors, but the decoy claims it’s instead a sign of continued civil unrest and dissatisfaction with the government in Hong Kong.

Figure 6. Decoy allegedly from the Justice & Peace Commission of the Hong Kong Catholic Diocese

The final decoy is an invitation to an April 4, 2016 wreath laying event held by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China. The event commemorated the 28th anniversary of the Tiananmen Square massacre and related events, information to which China heavily censors access for mainland Chinese citizens.

Figure 7. Decoy for an April 4, 2016 wreath laying event commemorating the Tiananmen Square massacre held by the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements of China.

Conclusion

The venerable Poison Ivy has been revamped and used to continue targeted attacks against pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong. It’s fairly common to see actors retool malware to make it harder to detect, though it was rarely seen before with Poison Ivy. The updated execution and communications mechanisms of SPIVY offer insight into the ever changing tools, techniques, and practices of targeted attackers. Unit 42 will continue to follow these attacks and any new Poison Ivy variants and provide updates as we uncover new information. It is clearly demonstrated by this recent campaign that an old dog can learn new tricks.

Pro-democratic activists in Hong Kong have increasingly been targeted by APT campaigns. Below are links to several related reports from different researchers. We don't necessarily link the activity in this blog to any of the specific campaigns cited in the links; instead, they are provided for situational awareness.

- October 2014 blog from Volexity titled "Democracy in Hong Kong Under Attack"

- June 2015 blog from Citizen Lab titled "Targeted Attacks against Tibetan and Hong Kong Groups Exploiting CVE-2014-4114"

- December 2015 blog from FireEye titled "China-based Cyber Threat Group Uses Dropbox for Malware Communications and Targets Hong Kong Media Outlets"

- April 2016 blog from Citizen Lab titled "Between Hong Kong and Burma: Tracking UP007 and SLServer Espionage Campaigns"

Palo Alto Networks customers can identify SPIVY command and control traffic using Threat Prevention signature ID and AutoFocus users can track this family using the SPIVY tag.

IOCs

Weaponized EPS Docs:

13bdc52c2066e4b02bae5cc42bc9ec7dfcc1f19fbf35007aea93e9d62e3e3fd0

4d38d4ee5b625e09b61a253a52eb29fcf9c506ee9329b3a90a0b3911e59174f2

9c6dc1c2ea5b2370b58b0ac11fde8287cd49aee3e089dbdf589cc8d51c1f7a9e

Loader Files

RasTls.exe - legitimate, signed binary that is used in the sideloading process

0191cb2a2624b532b2dffef6690824f7f32ea00730e5aef5d86c4bad6edf9ead

ssMUIDLL.dll - 7a424ad3f3106b87e8e82c7125834d7d8af8730a2a97485a639928f66d5f6bf4

Poison Ivy shellcode files

c707716afde80a41ce6eb7d6d93da2ea5ce00aa9e36944c20657d062330e13d8

0414bd2186d9748d129f66ff16e2c15df41bf173dc8e3c9cbd450571c99b3403

C2 Domains

sent.leeh0m[.]org

found.leeh0m[.]org

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42