As mentioned in our previous blog, we observed the Sofacy group using a new persistence mechanism that we call “Office Test” to load their Trojan each time the user opened Microsoft Office applications. Following the report, we received several questions regarding this persistence method, specifically how it works and which versions of Microsoft Office were affected. This blog will serve as a technical analysis of this persistence method that security professionals and network defenders can use for awareness, as we believe it is likely additional threat groups will begin using this technique.

We have added a malicious behavior tag named OfficeDllSideloading to AutoFocus for Palo Alto Networks customers to track the usage of this persistence method.

Office Test Backstory

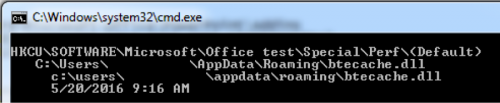

During our analysis of the delivery document used by the Sofacy group in recent targeted attacks, we saw the document create the following registry key:

HKEY_CURRENT_USER\Software\Microsoft\Office test\Special\Perf

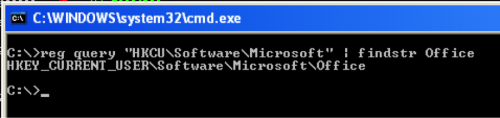

Based on our analysis, adding a path to a DLL to this registry key would load the DLL each time a Microsoft Office application was opened. We had not seen this registry key used for persistence before, so we looked into how this registry key results in the execution of a malicious payload. We checked a clean system with Microsoft Office installed, and confirmed that it did not have the key in the registry, as seen in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Windows Registry does not have the "Office Test" key by default with Microsoft Office Installation

We checked our WildFire data and found only a handful of samples using this registry key for persistence, all of which were used to load the Carberp variant of Sofacy. At the time, we thought the Sofacy group had discovered a new persistence technique, but to our surprise, Hexacorn had revealed this registry key in an April 2014 blog post. This suggests that the Sofacy group may not have discovered this persistence technique themselves, and as threat actors often do, absorbed an existing technique into their playbook.

DLL Loading Process

To determine how this registry key executed the malicious DLL, we analyzed activities that occur when the user opens the Microsoft Word application. We chose to analyze Word because we knew from our research on the Sofacy attacks that Word loaded the Trojan’s malicious DLL; however, other Microsoft Office applications were also discovered to be susceptible to this persistence method, which we will elaborate on in the next section.

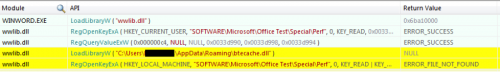

Figure 2 below shows the API function calls during the startup process that are related to the registry key. The API calls show Word (WINWORD.EXE) loading “wwlib.dll”, which is a legitimate library loaded by Word at runtime. The “wwlib.dll” library opens the registry key in question, queries its default value (NULL in Figure 2) and then loads the malicious DLL (“btecache.dll”) stored within this key using LoadLibraryW.

Figure 2 API functions called by Word that Loads Malicious DLL

The last activity seen by “wwlib.dll” in Figure 2 involves an attempt to open a handle to the same registry key within the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE hive, as follows:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Office test\Special\Perf

The attempt to open this key fails because the key does not exist with a default installation of Microsoft Office. In addition, using this registry key for persistence purposes is not ideal because the actor would need elevated privileges to modify registry keys in the HKLM hive. Instead, the threat actors created the “Office Test” registry key in the HKCU hive, which only requires the current account privileges to modify the key with a path to a malicious DLL.

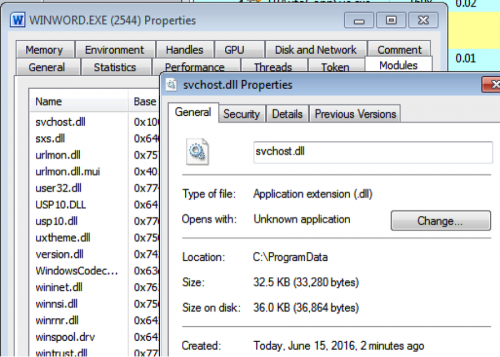

In the Sofacy attacks, the actors added its loader Trojan named “btecache.dll” (Figure 2) to the “Office Test” registry key. The loader Trojan locates and loads a second DLL from “C:\ProgramData\svchost.dll” into Word, as seen in Figure 3 and exits. The “svchost.dll” contains the functional code of the Carberp variant of the Sofacy Trojan, which remains running in Word until the user closes the application.

Figure 3 The payload "svchost.dll" running within Microsoft Word

Purpose of the Office Test Key

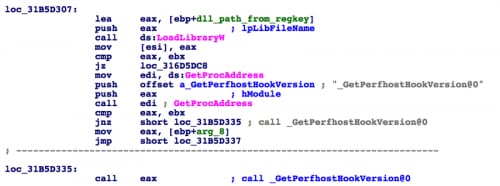

Based on the activities in the startup process, we saw the legitimate “wwlib.dll” library loading the malicious DLL from the registry key. We wanted to know why “wwlib.dll” would load a DLL from a key that was not added to the registry during the installation of Microsoft Office. Static analysis of “wwlib.dll” revealed that the DLL loads the library from the registry key, then attempts to resolve and call an API function named “_GetPerfhostHookVersion@0” from the loaded library, as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4 Code within wwlib.dll that loads a DLL from the registry and attempts to resolve and call _GetPerfhostHookVersion@0

When “wwlib.dll” uses the LoadLibraryW function to load the DLL from the registry key, it runs the DllEntryPoint exported function in the DLL. In the case of Sofacy’s “btecache.dll”, the DllEntryPoint function locates the second DLL called “svchost.dll”, loads and runs its functional code. The “btecache.dll” file does not contain an exported function named “_GetPerfhostHookVersion@0”, but this does not matter as the code in Figure 4 would fail to resolve the API function but would continue executing without calling the API.

In addition to “_GetPerfhostHookVersion@0”, the “wwlib.dll” library also attempts to resolve several additional exported functions from the DLL loaded from the registry, specifically with names that contain the following:

_InitPerf

_PerfCodeMarker

_UnInitPerf

It appears that Word (and other Microsoft Office applications) use this registry key to load DLLs in order to conduct performance evaluations and other debugging tasks during development or testing phases of the applications. This would explain the reason why the “Software\Microsoft\Office test\Special\Perf” registry keys are not created during the installation of Microsoft Office.

We also discovered that the library will attempt to load a DLL from the following registry key in the HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE hive, whose key name “RuntimePerfMeasurement” further suggests that “wwlib.dll” uses these registry keys for performance testing and debugging purposes:

HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\Software\Microsoft\Office test\Special\Perf\RuntimePerfMeasurement

Susceptible Applications and Versions

To see which versions of Word were susceptible to this persistence mechanism, we checked “wwlib.dll” in the following Word versions: 2003, 2007, 2010, 2013, 2015 and 2016. We were able to confirm “wwlib.dll” from Office 2007, 2010, 2013, 2015 and 2016 would load a DLL from the “Office Test” registry key discussed in this blog. Office 2003 would not load a DLL from this registry key and it did not have a “wwlib.dll” file.

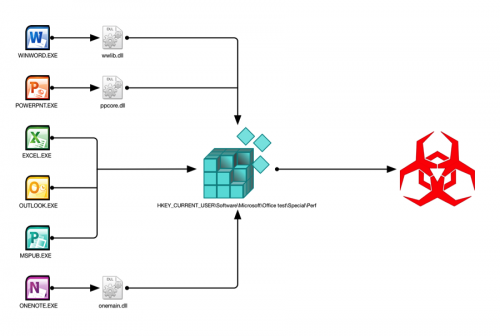

We also tested other Microsoft Office applications to see which would load a DLL from the “Office Test” registry key, which includes Word, Powerpoint, Excel, Outlook, OneNote and Publisher. It is interesting to note, that some applications in the Office suite do not need to call another DLL to load the malicious payload via the registry persistence mechanism (such as Word using wwlib.dll) and instead will load the malicious payload directly from the application. Figure 5 shows a graphical representation of applications loading the payload directly from the executable versus using a separate DLL file.

Figure 5 Office Test workflow

Simple Protection

During our research, we found that the "Office Test" persistence technique could be easily defeated by manually creating the registry key “HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Office test” and removing the current user’s account write permissions for this key. Microsoft Office does not require this registry key to operate and does not even create the registry key during installation; therefore, adding this key as read-only will have no effect on the usability of Microsoft Office applications. The steps taken to defeat the “Office Test” persistence mechanism will be outlined below and could also be easily scripted or pushed to systems via group policy.

Disclaimer: Modifying the registry can cause serious problems that may require you to reinstall your operating system. We cannot guarantee that problems resulting from the incorrect use of the registry can be solved. Use the information provided at your own risk.

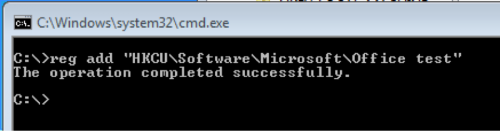

First, we created the "HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Office test" via the “reg” command. Open a command prompt (cmd.exe) and input the following:

reg add "HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Office test"

Figure 6 The "reg" command used to create the "Office test" registry key

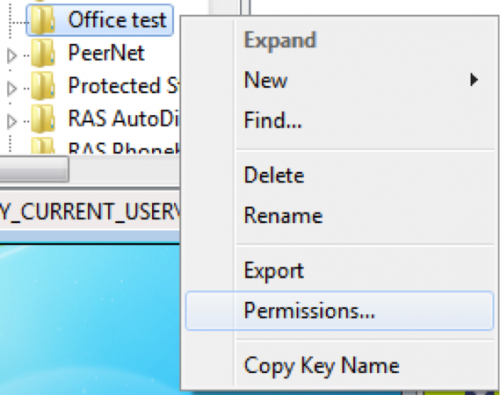

We then navigated to the newly created registry key using the “regedit” application. By right clicking on the key, we can access the permissions associated with the key, as seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7 Right clicking key allows access to permissions

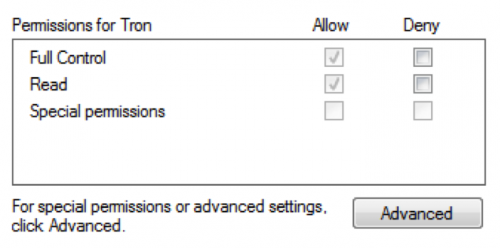

The current user has “Full Control” permissions for this registry key, as seen in Figure 8. This permission allows an actor to write the path to the Trojan to the “Special\Perf” sub-key. The “Read” control in Figure 8 allows Microsoft Office to read the contents of this key and its sub-keys, which is how the actor leverages this technique to load a malicious DLL into Office applications. To defeat this persistence mechanism, we can remove the current user’s write permissions to this key by clicking the “Advanced” button.

Figure 8 Current user's default permissions to the "Office test" registry key

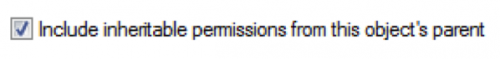

The current user was granted “Full Control” permissions to this registry key because it inherited permissions from its parent object, which ultimately inherited its permissions from the HKEY_CURRENT_USER hive. To remove the user’s write permissions to this registry key, we first must remove the inherited permissions by unchecking the box seen in Figure 9.

Figure 9 Remove inherited permissions by unchecking this box

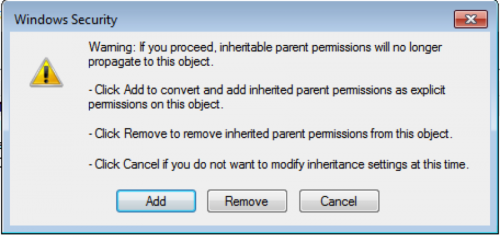

By unchecking the box in Figure 9, the dialog box in Figure 10 pops up, which provides options for “Remove” to remove all permissions from this key or “Add” to set specific permissions for the user.

Figure 10 Dialog box displayed after removing the registry key's inherited permissions

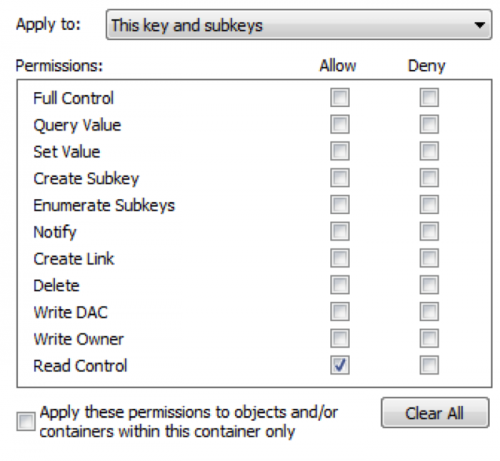

Here we will click “Add”, select the current user, then press the “Edit” button to set specific permissions for this user. In the next dialog, click the “Clear All” button first to remove all existing permissions then select only “Read Control”, as seen in Figure 11.

Figure 11 Read-only permissions assigned to this key

With the “Read Control” permission, Microsoft Office products are still able to read from this registry key, but malicious documents will not be able to write to this key. We tested this simple registry modification against the delivery document used by Sofacy discussed in our previous blog and discovered that while the delivery document was still able to exploit our analysis system, the payload would not be able to run when the user opened Microsoft Office applications, thus creating a benign infection.

Autoruns Detecting Office Test

Unit 42 reached out to notify Microsoft of the Office Test persistence mechanism and its use by a threat group in targeted attacks. On July 4, 2016, Microsoft released a new version of Autoruns, specifically v13.52 that includes checks for the Office Test registry keys. We downloaded Autoruns v13.52 and tested both the GUI (Autoruns.exe) and CLI (autorunsc.exe) versions of the tool on a system compromised with the Sofacy tool that used this persistence technique. Figure 12 and Figure 13 below show the two Autoruns tools detecting the use of this registry key for persistence.

Figure 12 GUI version of Autoruns detecting Office Test persistence mechanism

Figure 13 Autorunsc detecting the Office Test persistence mechanism

Conclusion

The "Office Test" persistence mechanism allows threat actors to execute a Trojan each time a user runs any of the Office applications. This persistence mechanism loads a malicious DLL by leveraging a registry key that appears to be used during the development and testing of Microsoft Office applications. The use of this registry key for persistence is quite clever, as it requires user interaction to load and execute the malicious payload, which makes automated analysis in sandboxes challenging. Low awareness of this persistence method, coupled with the sandbox evasion obtained from user interactions, makes this a potentially attractive persistence method that we believe may be used in future attacks. Unit 42 suggests monitoring for systems that have this registry key already created, as it is possible a threat is already using the key for persistence purposes. Microsoft has added the “Office Test” registry keys to its Autoruns tool for detection purposes as well. Also, we suggest disabling this persistence method by creating the “Office test” registry key in read-only mode as outlined in this blog.

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42