This post is also available in: 日本語 (Japanese)

Executive Summary

This tutorial is designed for security professionals who investigate suspicious network activity and review packet captures (pcaps). Familiarity with Wireshark is necessary to understand this tutorial, which focuses on Wireshark version 3.x.

Emotet is an information-stealer first reported in 2014 as banking malware. It has since evolved with additional functions such as a dropper, distributing other malware families like Gootkit, IcedID, Qakbot and Trickbot.

Today’s Wireshark tutorial reviews recent Emotet activity and provides some helpful tips on identifying this malware based on traffic analysis.

Note: These instructions assume you have customized Wireshark as described in our previous Wireshark tutorial about customizing the column display.

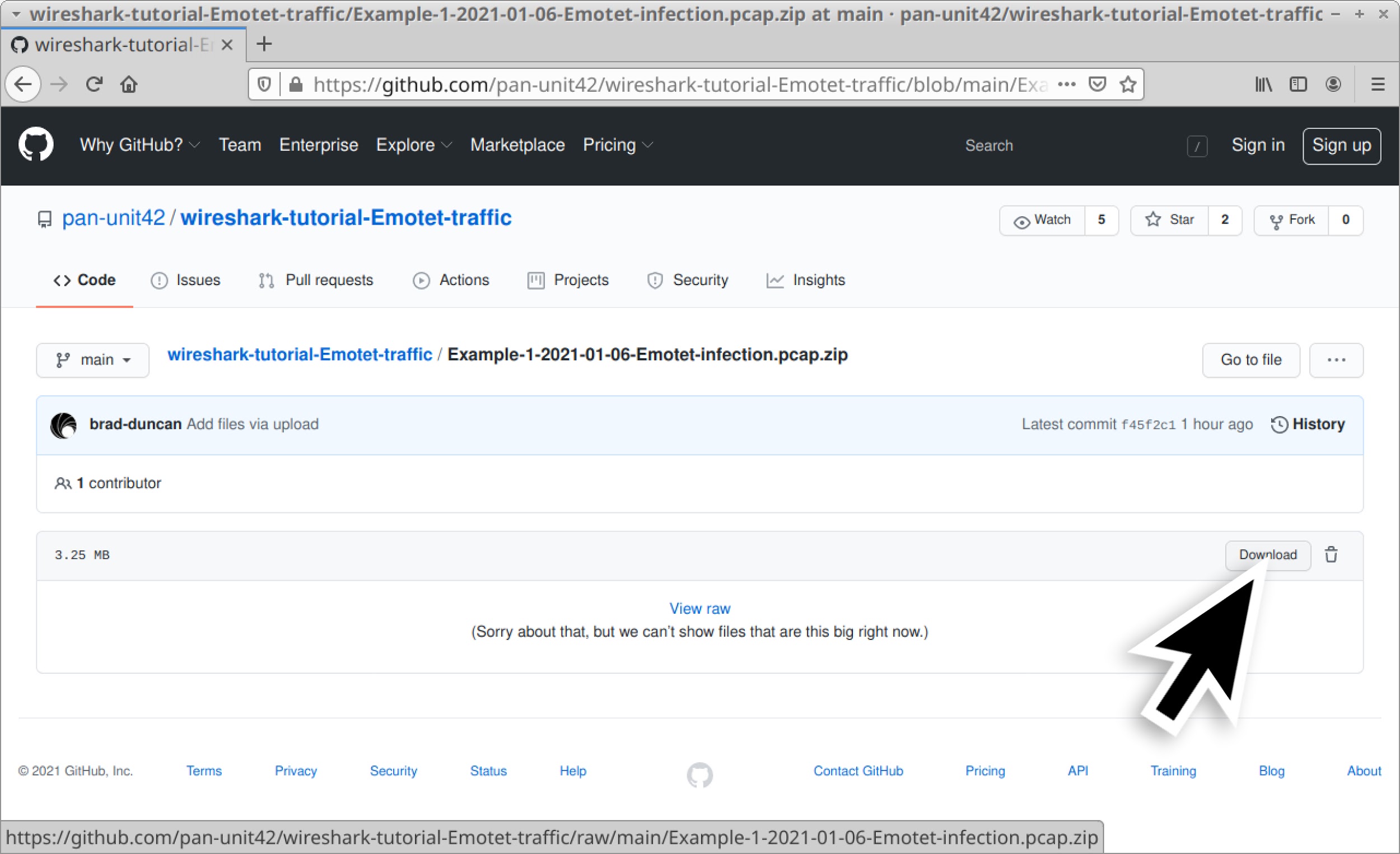

You will need to access a GitHub repository with ZIP archives containing the pcaps used for this tutorial.

Warning: Some of the pcaps used for this tutorial contain Windows-based malware. There is a risk of infection if using a Windows computer. If possible, we recommend you review these pcaps in a non-Windows environment like BSD, Linux or macOS.

Chain of Events for an Emotet Infection

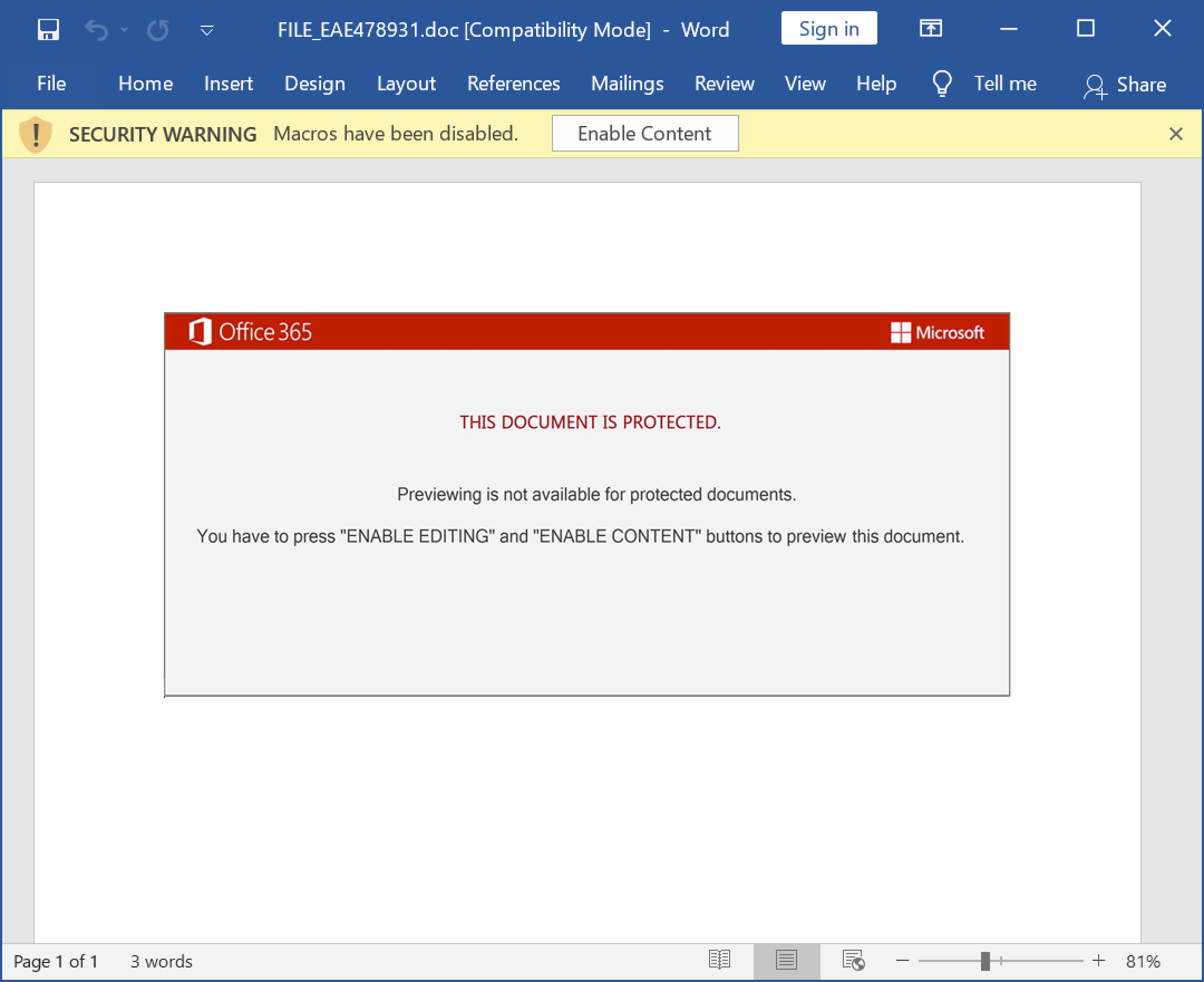

To understand network traffic caused by Emotet, you must first understand the chain of events leading to an infection. Emotet is commonly distributed through malicious spam (malspam) emails. The critical step in an Emotet infection chain is a Microsoft Word document with macros designed to infect a vulnerable Windows host.

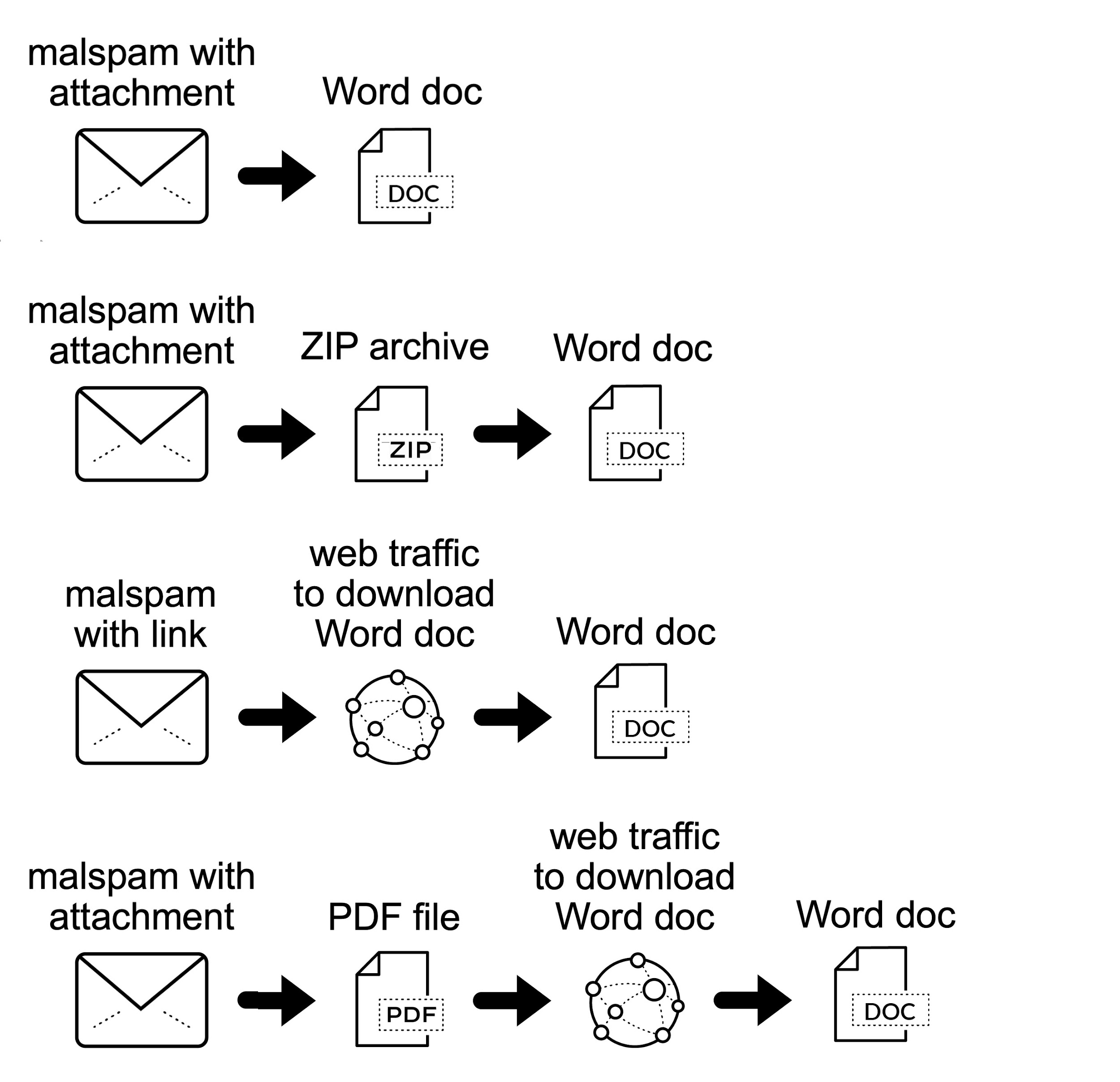

Malspam spreading Emotet uses different techniques to distribute these Word documents.

The malspam may contain an attached Microsoft Word document or have an attached ZIP archive containing the Word document. In recent months, we have seen several examples where these ZIP archives are password-protected. Some emails distributing Emotet do not have any attachments. Instead, they contain a link to download the Word document.

In previous years, malspam pushing Emotet has also used PDF attachments with embedded links to deliver these Emotet Word documents.

Figure 2 illustrates these four distribution techniques.

After the Word document is delivered, if a victim opens the document and enables macros on a vulnerable Windows host, the host is infected with Emotet.

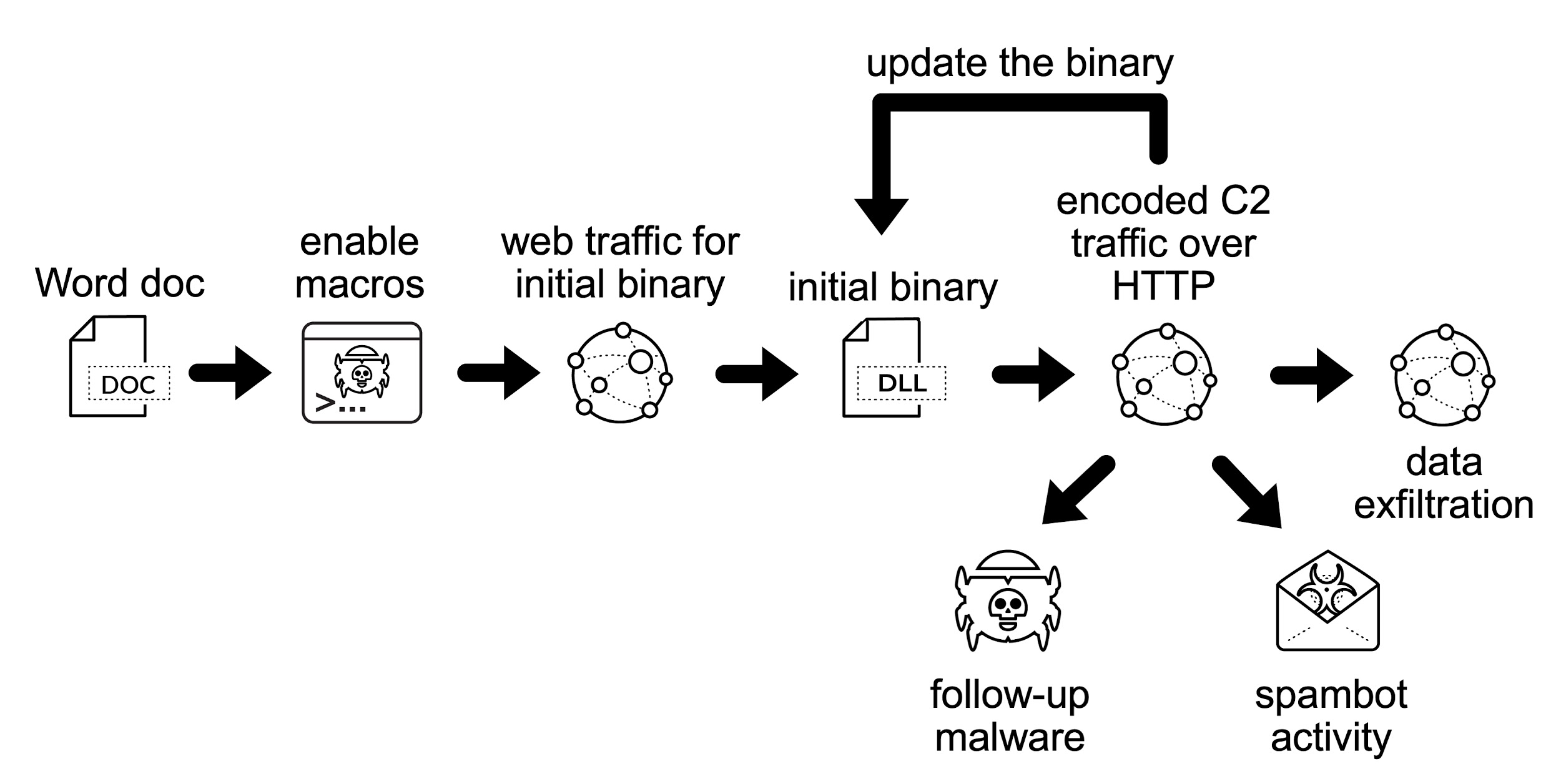

From a traffic perspective, we see the following steps from an Emotet Word document to an Emotet infection:

- Web traffic to retrieve the initial binary.

- Encoded/encrypted command and control (C2) traffic over HTTP.

- Additional infection traffic if Emotet drops follow-up malware.

- SMTP traffic if Emotet uses the infected host as a spambot.

Figure 3 shows a flowchart of network activity we might find during an Emotet infection.

Since Dec. 21, 2020, the initial binary for Emotet has been a Windows DLL file. Previously, this binary had been a Windows EXE file.

Emotet C2 traffic consists of encoded or otherwise encrypted data sent over HTTP. This C2 activity can use either standard or non-standard TCP ports associated with HTTP traffic. This C2 activity also consists of data exfiltration and traffic to update the initial Emotet binary.

Since Emotet is also a malware dropper, the victim may become infected with other malware. Analysts should search for traffic from other malware when investigating traffic from an Emotet-infected host.

Finally, an Emotet-infected host may also become a spambot generating large amounts of traffic over TCP ports associated with SMTP like TCP ports 25, 465 and 587.

Pcaps of Emotet Infection Activity

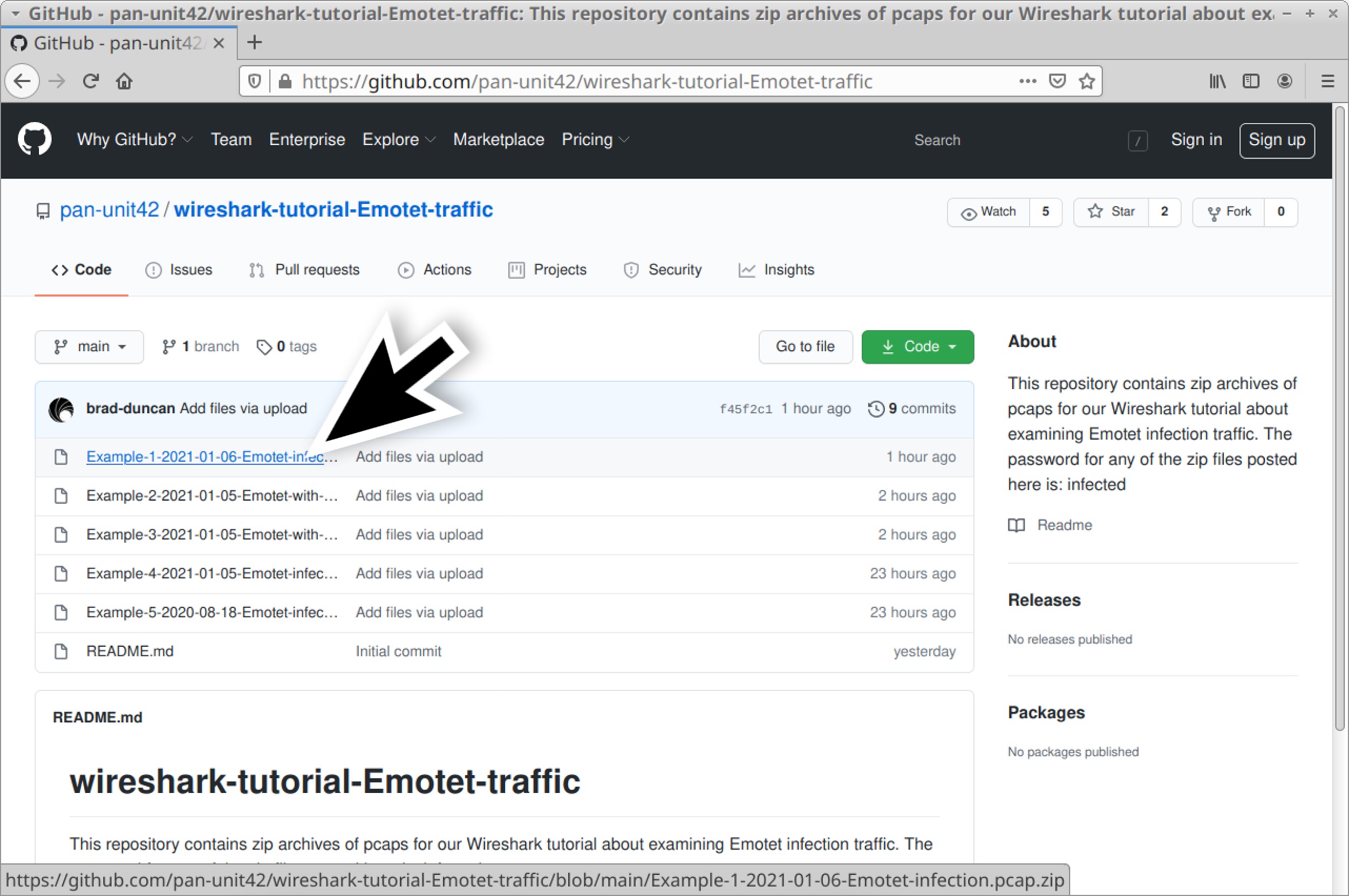

Five password-protected ZIP archives containing pcaps of recent Emotet infection traffic are available at this GitHub repository. Once on the GitHub page, click on each of the ZIP archive entries and download them, as shown in Figures 4 and 5.

Use infected as the password to extract pcaps from these ZIP archives. This should give you the following five pcap files:

- Example-1-2021-01-06-Emotet-infection.pcap

- Example-2-2021-01-05-Emotet-with-spambot-traffic-part-1.pcap

- Example-3-2021-01-05-Emotet-with-spambot-traffic-part-2.pcap

- Example-4-2021-01-05-Emotet-infection-with-Trickbot.pcap

- Example-5-2020-08-18-Emotet-infection-with-Qakbot.pcap

Example 1: Emotet Infection Traffic

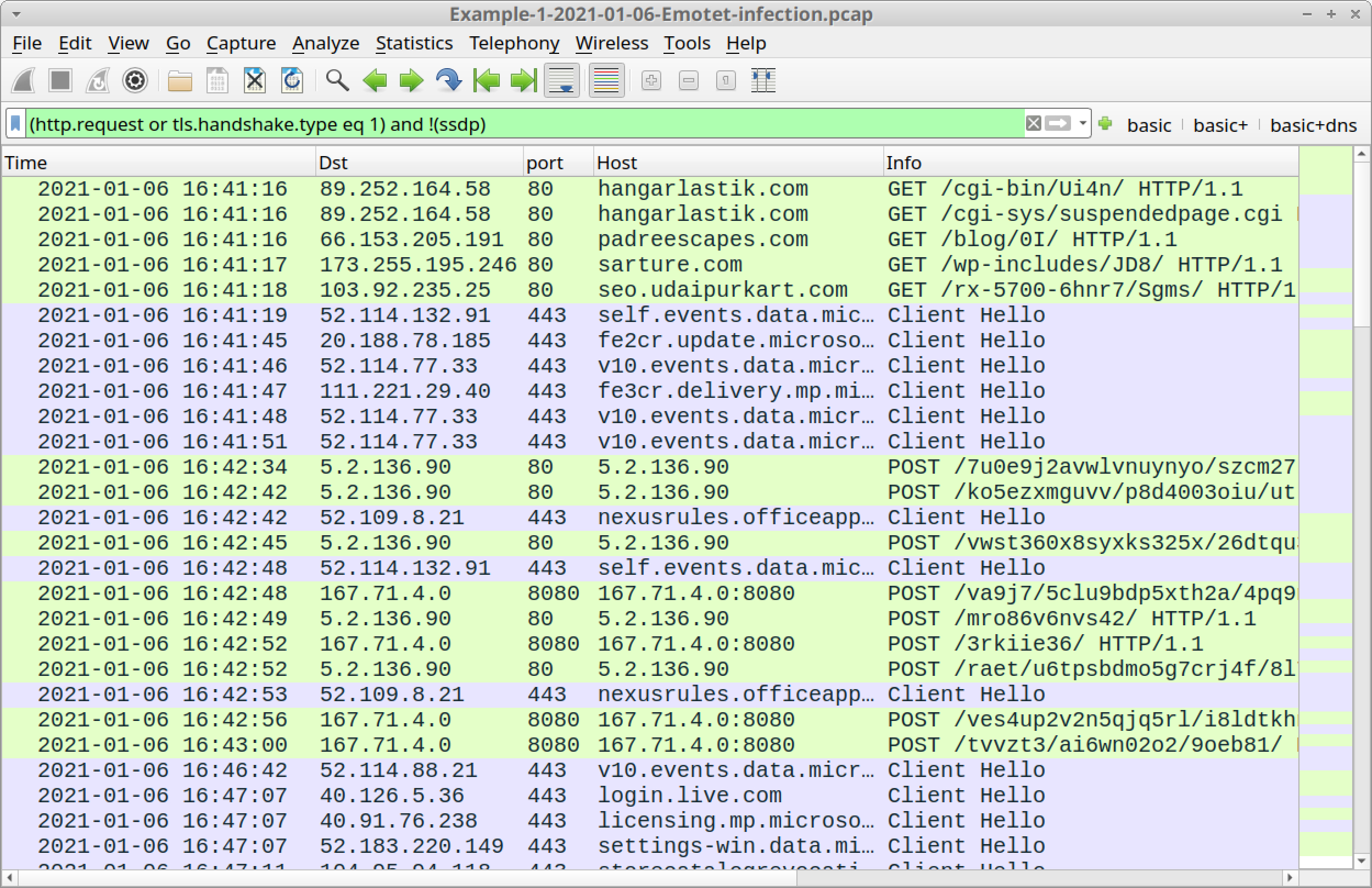

Open Example-1-2021-01-06-Emotet-infection.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter as described in our previous tutorial about Wireshark filters. The basic filter for Wireshark 3.x is:

(http.request or tls.handshake.type eq 1) and !(ssdp)

If you’ve set up Wireshark according to our initial tutorial about customizing Wireshark displays, your display should look similar to Figure 6.

As shown in Figure 6, the first five HTTP GET requests represent four URLs used to retrieve the initial Emotet DLL. The traffic is:

- hangarlastik[.]com GET /cgi-bin/Ui4n/

- hangarlastik[.]com GET /cgi-sys/suspendedpage.cgi

- padreescapes[.]com GET /blog/0I/

- sarture[.]com GET /wp-includes/JD8/

- seo.udaipurkart[.]com GET /rx-5700-6hnr7/Sgms/

The first two URLs indicate hangarlastik[.]com no longer had the Emotet DLL file it had been hosting. Follow TCP streams for each of these requests to see replies to each of the HTTP GET requests.

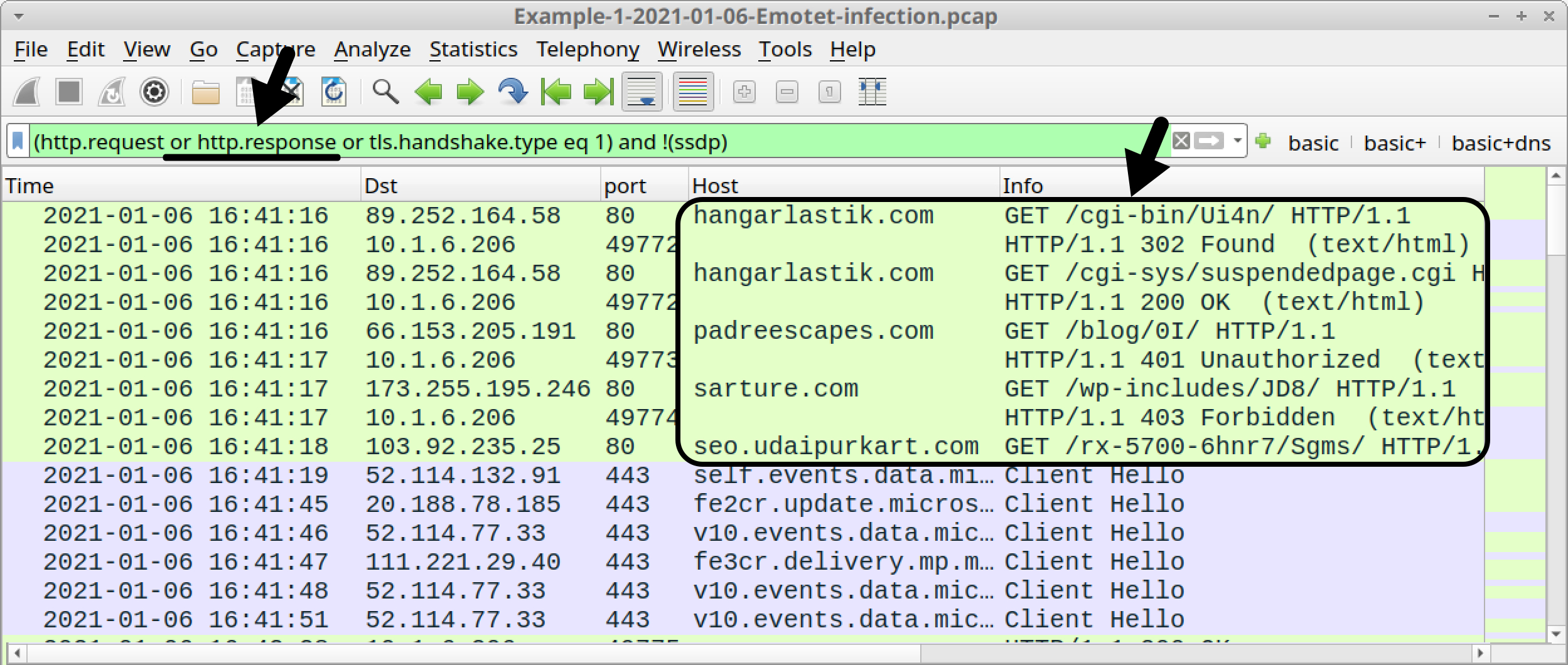

An easier way to see the HTTP responses is to update your Wireshark basic web filter to include HTTP responses:

(http.request or http.response or tls.handshake.type eq 1) and !(ssdp)

This will show HTTP responses in the Info column, as illustrated in Figure 7.

Now we have a clearer picture of what happened when the Word macro tried to retrieve an Emotet DLL:

- hangarlastik[.]com GET /cgi-bin/Ui4n/

- HTTP/1.1 302 Found

- hangarlastik[.]com GET /cgi-sys/suspendedpage.cgi

- HTTP/1.1 200 OK

- padreescapes[.]com GET /blog/0I/

- HTTP/1.1 401 Unauthorized

- sarture[.]com GET /wp-includes/JD8/

- HTTP/1.1 403 Forbidden

- seo.udaipurkart[.]com GET /rx-5700-6hnr7/Sgms/

The only 200 OK was a reply for a suspended page notification from hangarlastik[.]com.

The HTTP GET request to seo.udaipurkart[.]com does not show a response, so follow the TCP stream for this request, as shown in Figure 8.

![Figure 8. Following TCP stream for the HTTP request to seo.udaipurkart[.]com.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/word-image-37.jpeg)

The TCP stream shows indicators that seo.udaipurkart[.]com returned a Windows DLL file, as shown in Figure 9.

![Figure 9. Indicators of a DLL file returned from seo.udaipurkart[.]com.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/word-image-38.jpeg)

The SHA256 hash for this extracted DLL is:

8e37a82ff94c03a5be3f9dd76b9dfc335a0f70efc0d8fd3dca9ca34dd287de1b

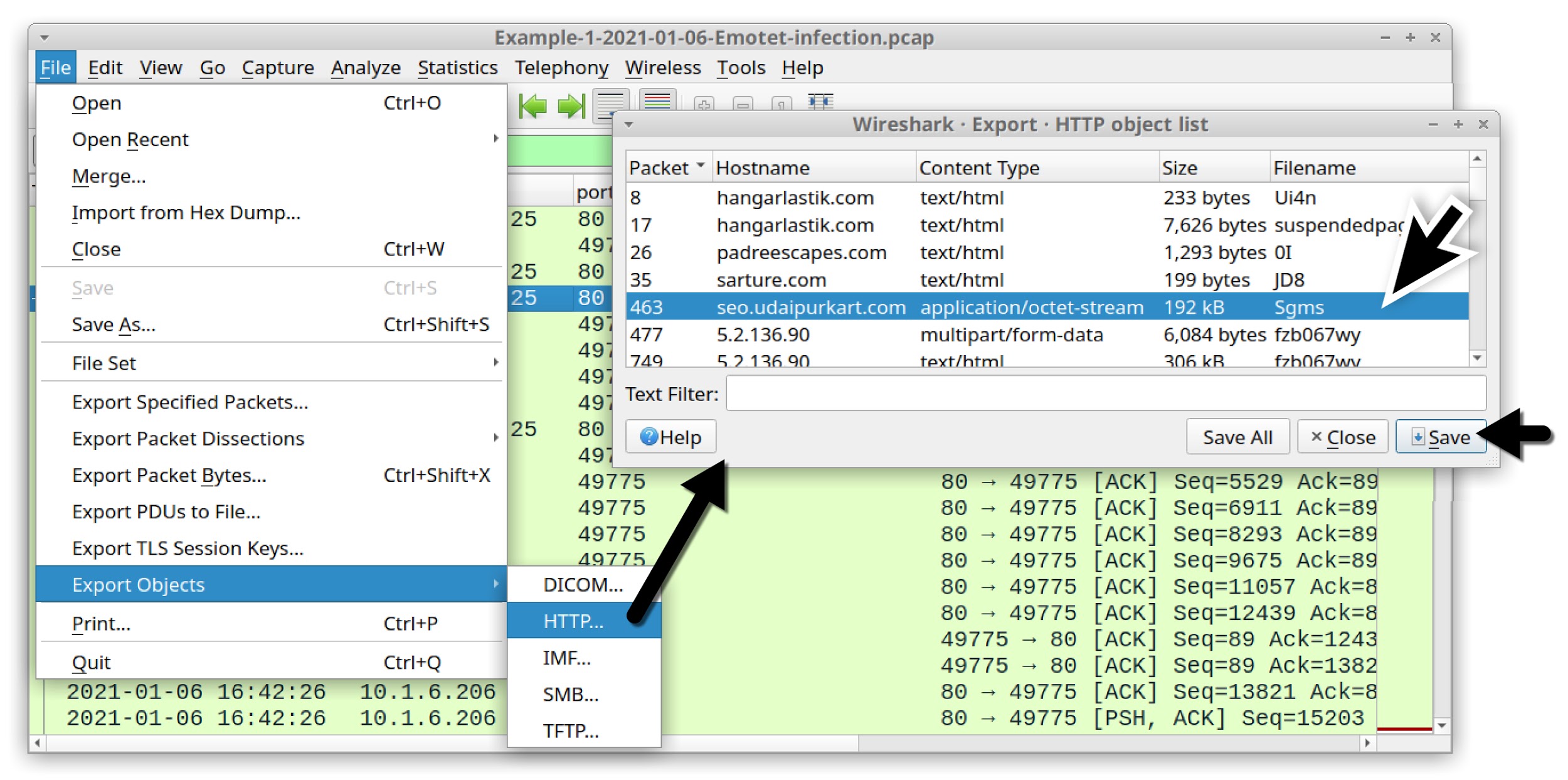

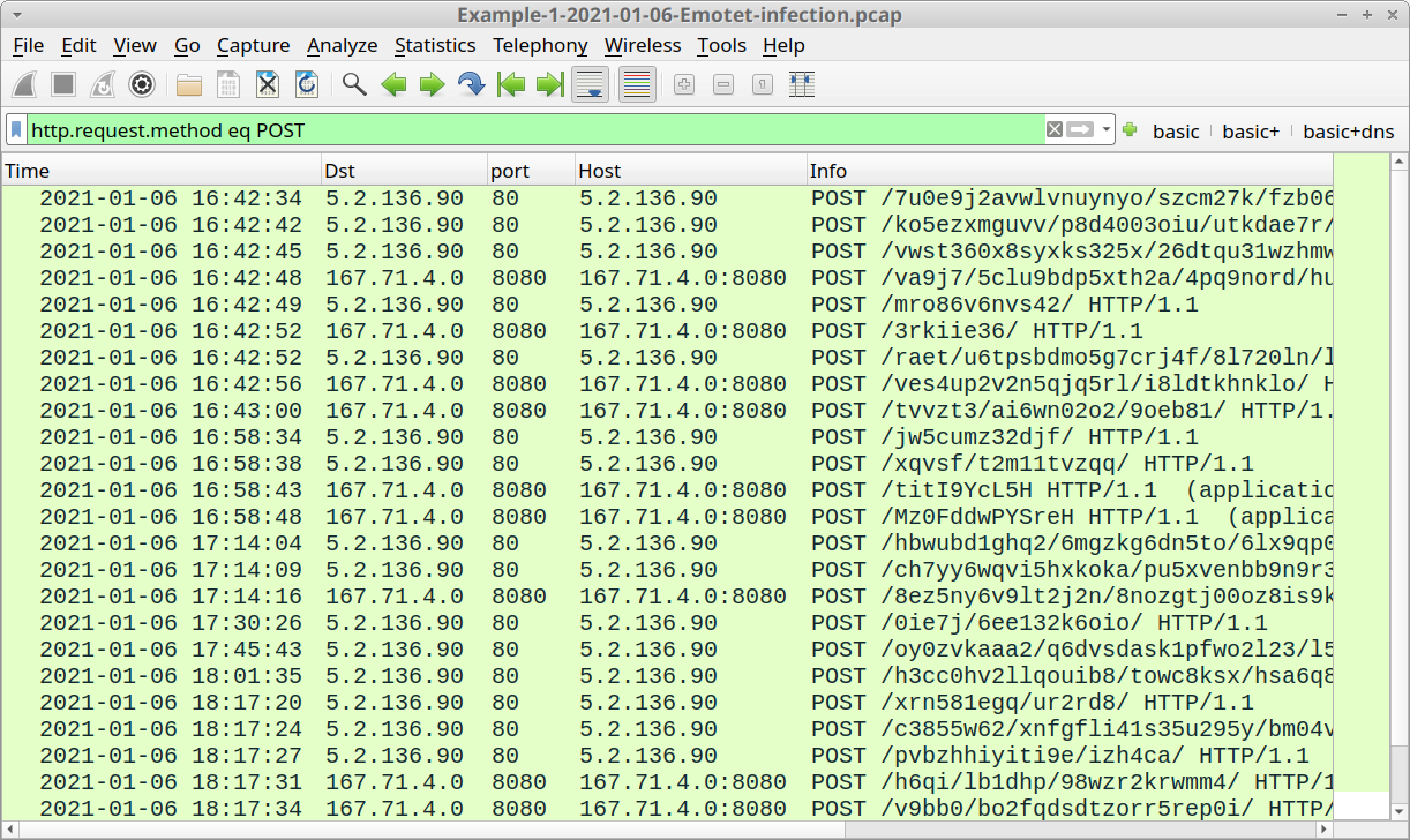

Emotet C2 traffic is encoded data sent using HTTP POST requests. You can easily find these requests in Wireshark using the following filter:

http.request.method eq POST

The results are shown in Figure 11.

In our first pcap, Emotet C2 traffic consists of HTTP POST requests to:

- 5.2.136[.]90 over TCP port 80

- 167.71.4[.]0 over TCP port 8080

Emotet generates two types of HTTP POST requests for its C2 traffic. The first type of POST request ends with HTTP/1.1. The second type of POST request ends with HTTP/1.1 (application/x-www-form-urlencoded).

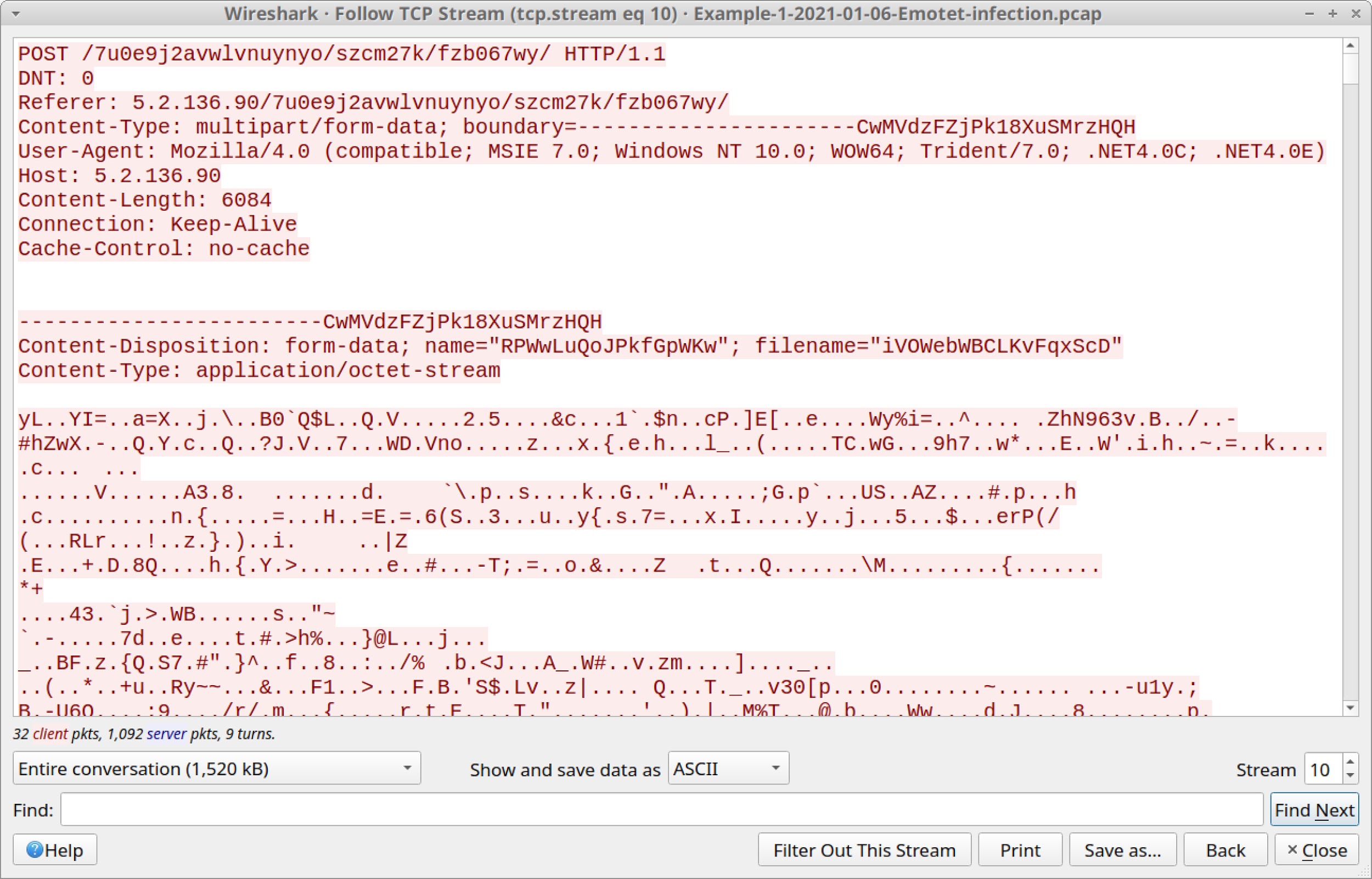

Follow the TCP stream for the initial HTTP request to 5.2.136[.]90 at 16:42:34 UTC to see an example of the first type of C2 POST request, as shown in Figure 12.

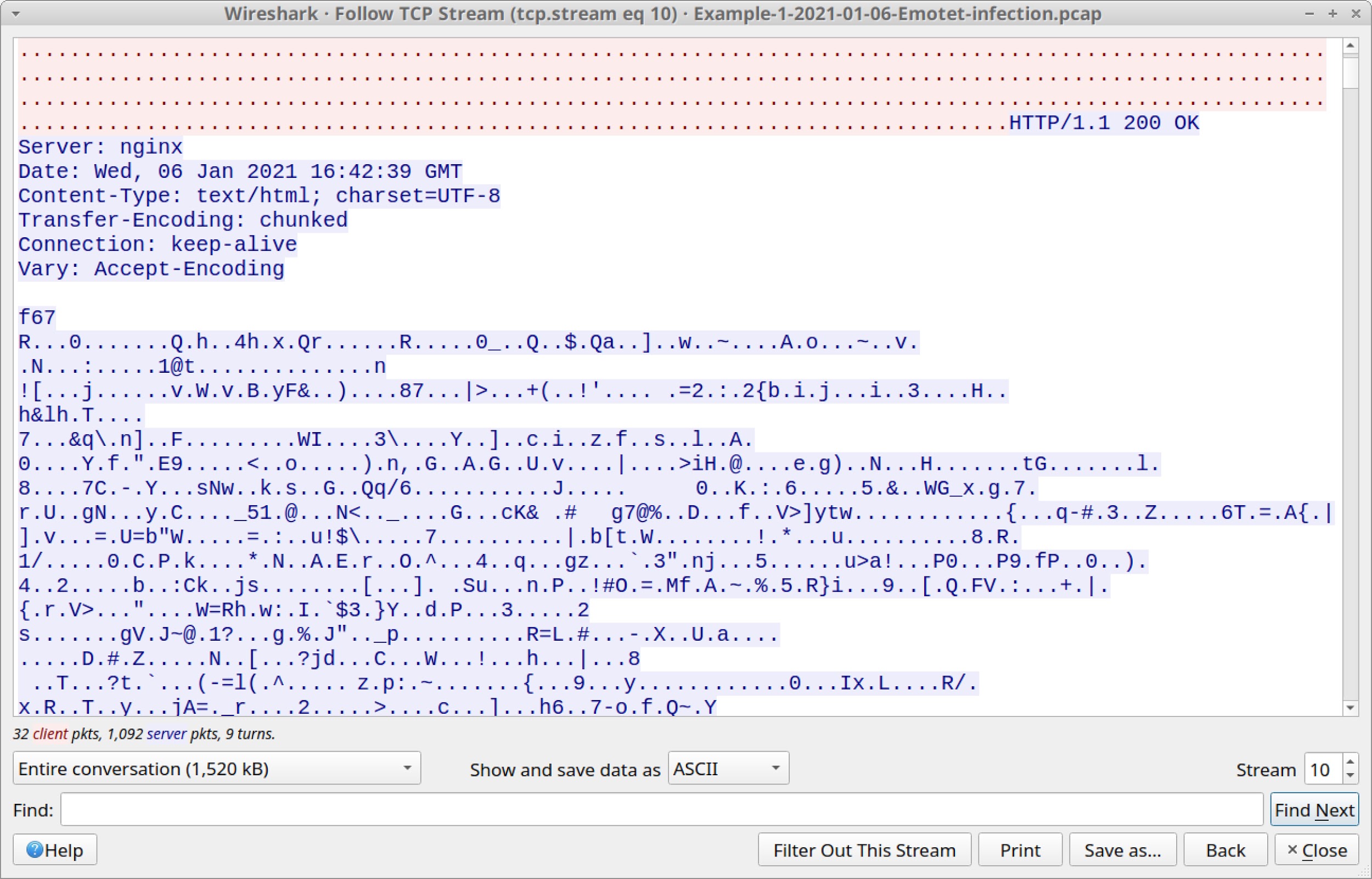

Figure 12 shows this POST request sends approximately 6 KB of form-data that appears to be an encoded or encrypted binary. Scroll down to the HTTP response to see encoded data returned from the server. Figure 13 shows the start of this encoded data.

This type of encoded or encrypted data is how Emotet botnet servers exchange data with an infected Windows host. This is also the channel Emotet uses to update the Emotet DLL and drop follow-up malware.

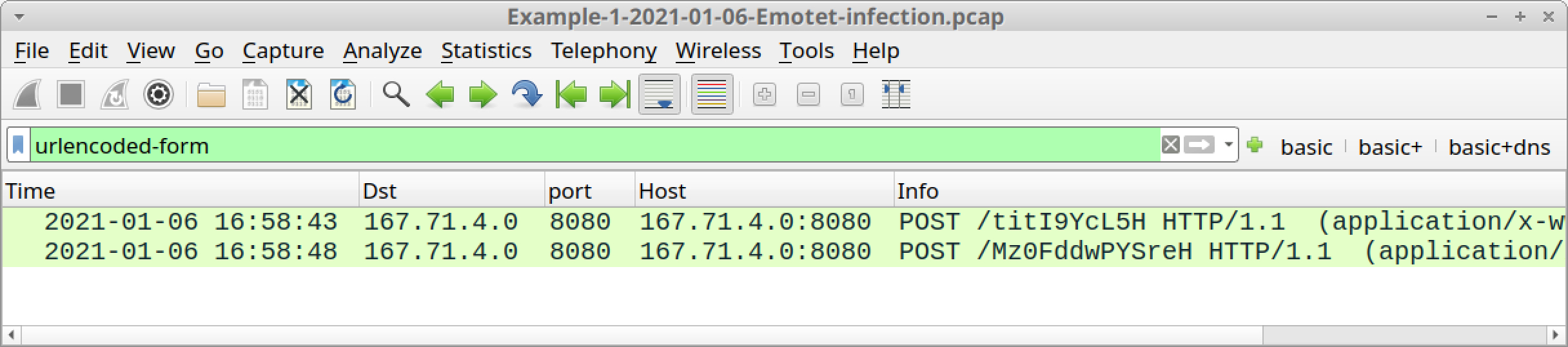

The second type of HTTP POST request for Emotet C2 traffic looks noticeably different than the first type. Use the following filter in Wireshark to easily find the second type of HTTP POST request:

urlencoded-form

This should return two HTTP POST requests to 167.71.4[.]0 over TCP port 8080, as shown in Figure 14.

Follow the TCP stream for the first of these two HTTP POST requests at 16:58:43 UTC. Review the traffic. The results are shown in Figure 15.

As shown in Figure 15, some of the data sent in the POST request is encoded as a base64 string with some URL encoding. For example, %2B is used for a + symbol, %2F represents / and %3D is used for =.

Data sent in response from the server is encoded or otherwise encrypted.

Our first pcap has no follow-up malware or other significant activity.

The only other activity is repeated connection attempts to 46.101.230[.]194 over TCP port 443. You can easily spot this activity by filtering on TCP SYN segments that are retransmissions. Use the following Wireshark filter:

tcp.analysis.retransmission and tcp.flags eq 0x0002

The results are shown in Figure 16.

An Internet search on 46.101.230[.]194 should reveal this IP address has been used for Emotet C2 activity.

The remaining traffic in the pcap is system traffic generated by a Microsoft Windows 10 host.

In our next pcap, we examine an Emotet infection with spambot activity.

Example 2: Emotet With Spambot Traffic, Part 1

Open Example-2-2021-01-05-Emotet-with-spambot-traffic-part-1.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 17.

Similar to our first example, we receive some HTTP GET requests before Emotet C2 traffic. These GET requests are attempts to download the initial Emotet DLL over web traffic. The first frame in the column display shows HTTPS traffic to obob[.]tv, which was probably a web request for the initial Emotet DLL, because this domain was reported as hosting an Emotet binary on Jan. 5, 2021, the same date as the traffic in our pcap.

Follow the TCP stream for the HTTP GET request to miprimercamino[.]com to confirm it returned an Emotet DLL. You should see indicators similar to Figure 9 from our first pcap. We can export the Emotet DLL returned from miprimercamino[.]com, as shown in Figure 18.

The SHA256 hash for the extracted DLL from our second pcap is:

963b00584d8d63ea84585f7457e6ddcac9eda54428a432f388a1ffee21137316

Again, we find two types of HTTP POST requests for Emotet C2 traffic. To filter for each type of Emotet C2 HTTP POST request, use the following Wireshark filters:

- First type: http.request method eq POST and !(urlencoded-form)

- Second type: urlencoded-form

Follow TCP streams for the HTTP POST requests returned by these filters and confirm they follow the same patterns seen in our first pcap.

After reviewing some examples of Emotet C2 traffic from this pcap, let’s move on to the spambot activity.

In this example, our infected host was turned into a spambot, so we also have SMTP traffic. The spambot SMTP traffic is encrypted, but we can easily find it by using our basic web filter and scrolling down the column display.

At 20:06:20 UTC, the pcap starts showing SSL/TLS traffic to TCP ports associated with the SMTP email protocol, like TCP ports 25, 465 and 587, as shown in Figure 19.

We can filter on smtp to find some of the SMTP commands before encrypted SMTP tunnels are established. Figure 20 shows the results.

We can sometimes find unencrypted SMTP from spambot traffic generated by an Emotet-infected Windows host. Unencrypted SMTP will reveal its message content, but the volume of encrypted SMTP from a spambot host is far greater than the volume of unencrypted SMTP. Therefore, most of the spambot messages from an Emotet-infected host are hidden within the encrypted traffic.

In this example, you should only see encrypted SMTP traffic.

But our next example is later from this same infection, when we finally saw some unencrypted SMTP.

Example 3: Emotet With Spambot Traffic, Part 2

Open Example-3-2021-01-05-Emotet-with-spambot-traffic-part-2.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 21.

In this pcap, we still see HTTP POST requests for Emotet C2 traffic, at least twice each minute. We can also find encrypted spambot activity similar to our previous pcap.

Spambot activity frequently generates a large amount of traffic. This pcap consists of 4 minutes and 42 seconds of spambot activity from the infected Windows host, and it’s over 21 MB of traffic.

We can quickly identify any unencrypted SMTP traffic by using the following Wireshark filter:

smtp.data.fragment

Figure 22 shows the results of this filter for our third pcap. The filter reveals five examples of Emotet malspam generated by the infected Windows host.

Follow the TCP stream for the last email from: "Gladisbel Miranda at 20:19:54 UTC. Examine what these messages look like, as shown in Figure 23.

We can export these five items of Emotet malspam by using the menu path File --> Export Objects --> IMF, as shown in Figure 24.

Export these emails and examine them. Ideally, we recommend doing this in a non-Windows environment. Thunderbird is a free email client you can use to see how a potential victim might view these emails.

As mentioned earlier, Emotet is also a malware downloader. Perhaps the most common malware distributed through Emotet is Trickbot.

Example 4: Emotet Infection with Trickbot

Open Example-4-2021-01-05-Emotet-infection-with-Trickbot.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 25.

This pcap does not have an HTTP GET request for an initial Emotet DLL. However, the first frame in our column display shows HTTPS traffic to fathekarim[.]com. This was probably a web request for the Emotet DLL, because this domain was reported as hosting an Emotet binary on Jan. 5, 2021, the same date as the traffic in our pcap.

You should find the same two types of HTTP POST requests associated with Emotet C2, as described in our previous two pcaps.

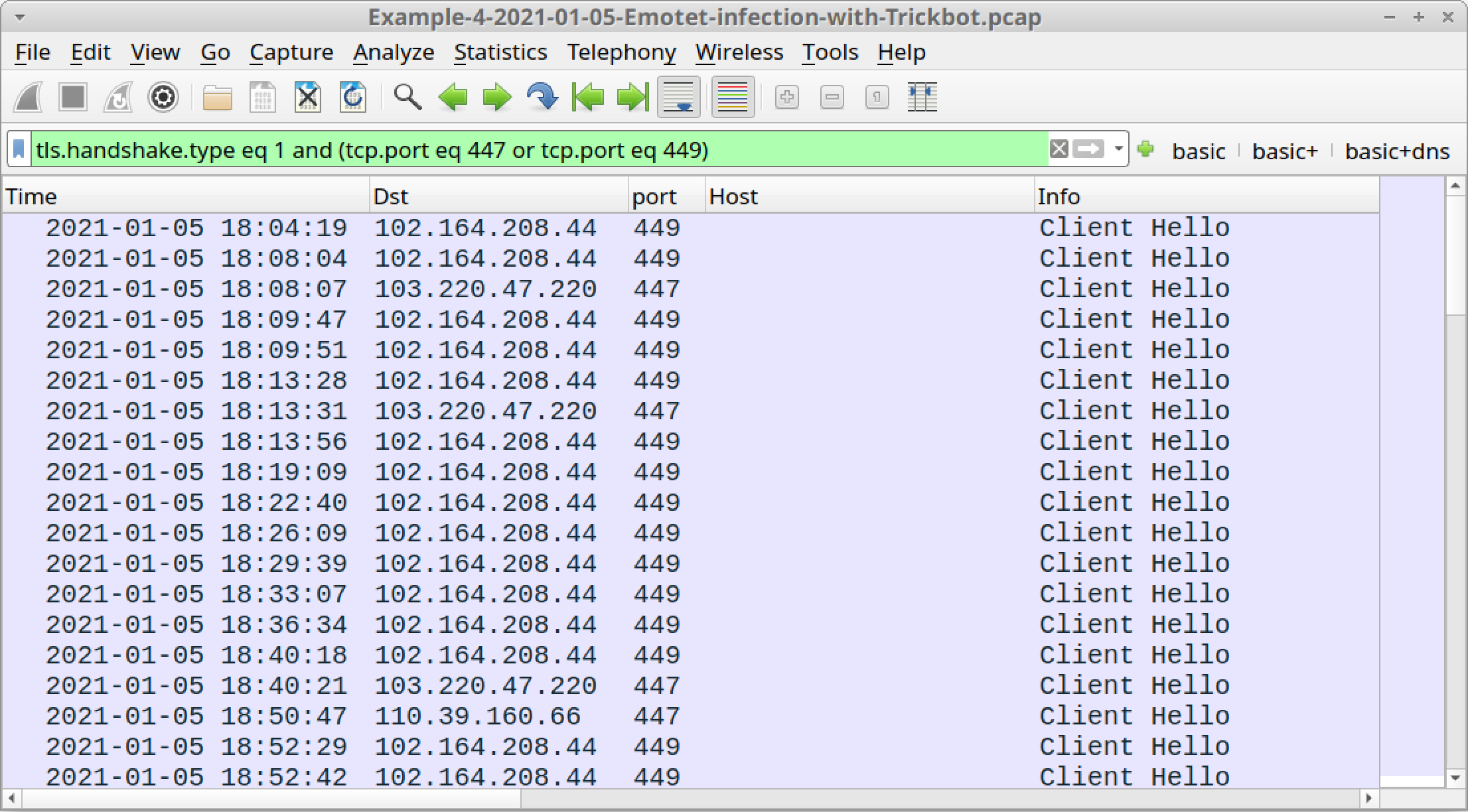

This pcap also contains indicators of a Trickbot infection. Use your basic web filter and scroll down to find Trickbot traffic, as shown in Figure 26.

We’ve reviewed Trickbot in our previous Wireshark tutorial on examining Trickbot infections, but here is a quick refresher. The following are common indicators for Trickbot:

- HTTPS traffic over TCP ports 447 or 449 without an associated domain or hostname.

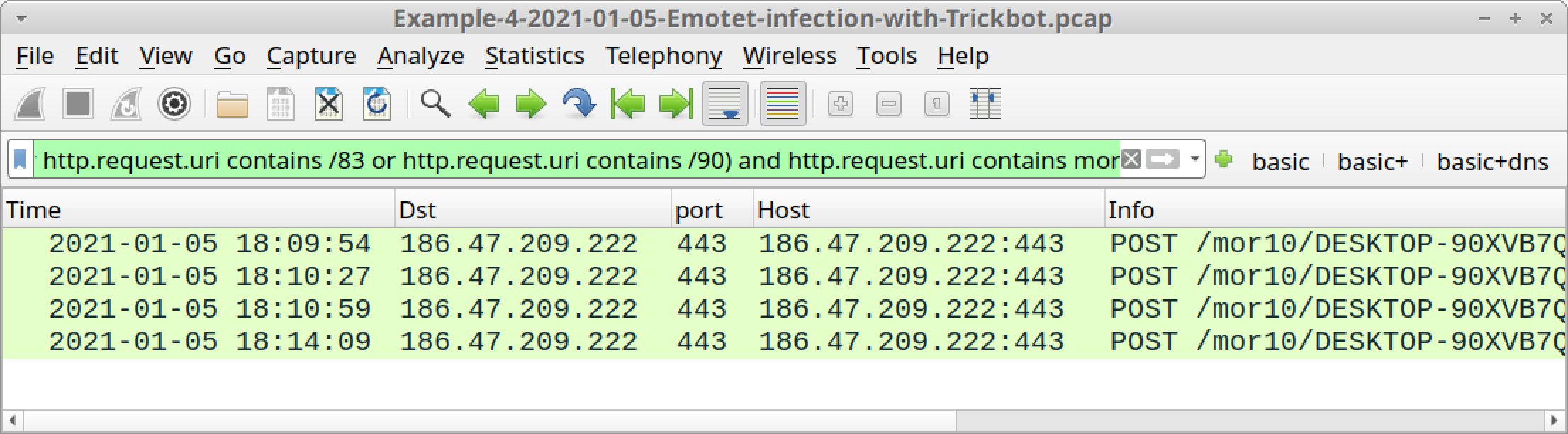

- HTTP POST requests over standard or non-standard TCP ports for HTTP traffic that end with /81/, /83/ or /90, which are associated with data exfiltration.

- With Trickbot from Emotet infections, the above HTTP POST requests start with /mor followed by a number (only one or two digits seen so far).

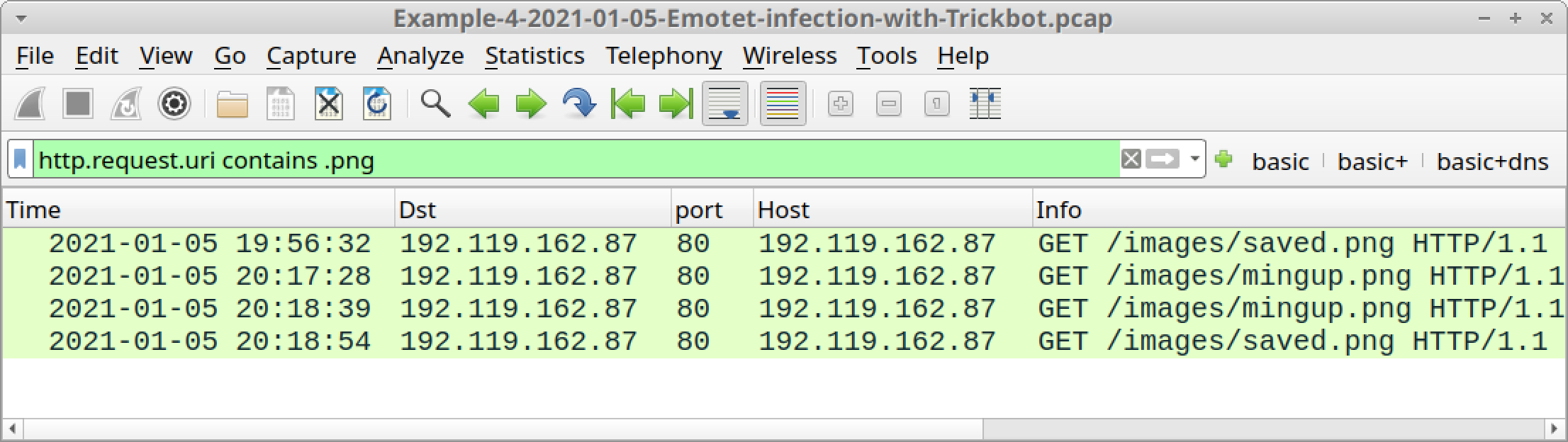

- HTTP GET requests for URLs that end in .png that return additional Trickbot binaries.

We can easily find these indicators using the following Wireshark filters:

- tls.handshake.type eq 1 and (tcp.port eq 447 or tcp.port eq 449)

- (http.request.uri contains /81 or http.request.uri contains /83 or http.request.uri contains /90) and http.request.uri contains mor

- http.request.uri contains .png

Figures 27-29 show the results from each of the above filters.

Follow TCP streams for each of the HTTP POST requests shown in Figure 28 to see if any password data was exfiltrated. The last HTTP POST request ending with /90 contains data about the infected Windows host and its environment.

Follow TCP streams for each of the HTTP POST requests shown in Figure 29 to see if any Windows binaries were returned. Doing so should reveal two Windows executable files. You can then export these binaries from the pcap using File --> Export Objects --> HTTP, as discussed in our previous examples.

SHA256 hashes for these two Windows binaries (both EXE files) are:

- 59e1711d6e4323da2dc22cdee30ba8876def991f6e476f29a0d3f983368ab461 for mingup.png

- ed8dea5381a7f6c78108a04344dc73d5669690b7ecfe6e44b2c61687a2306785 for saved.png

Trickbot is the most common malware distributed by Emotet, but it is not the only one. Qakbot is another type of malware frequently dropped on Emotet-infected Windows hosts.

Example 5: Emotet Infection With Qakbot

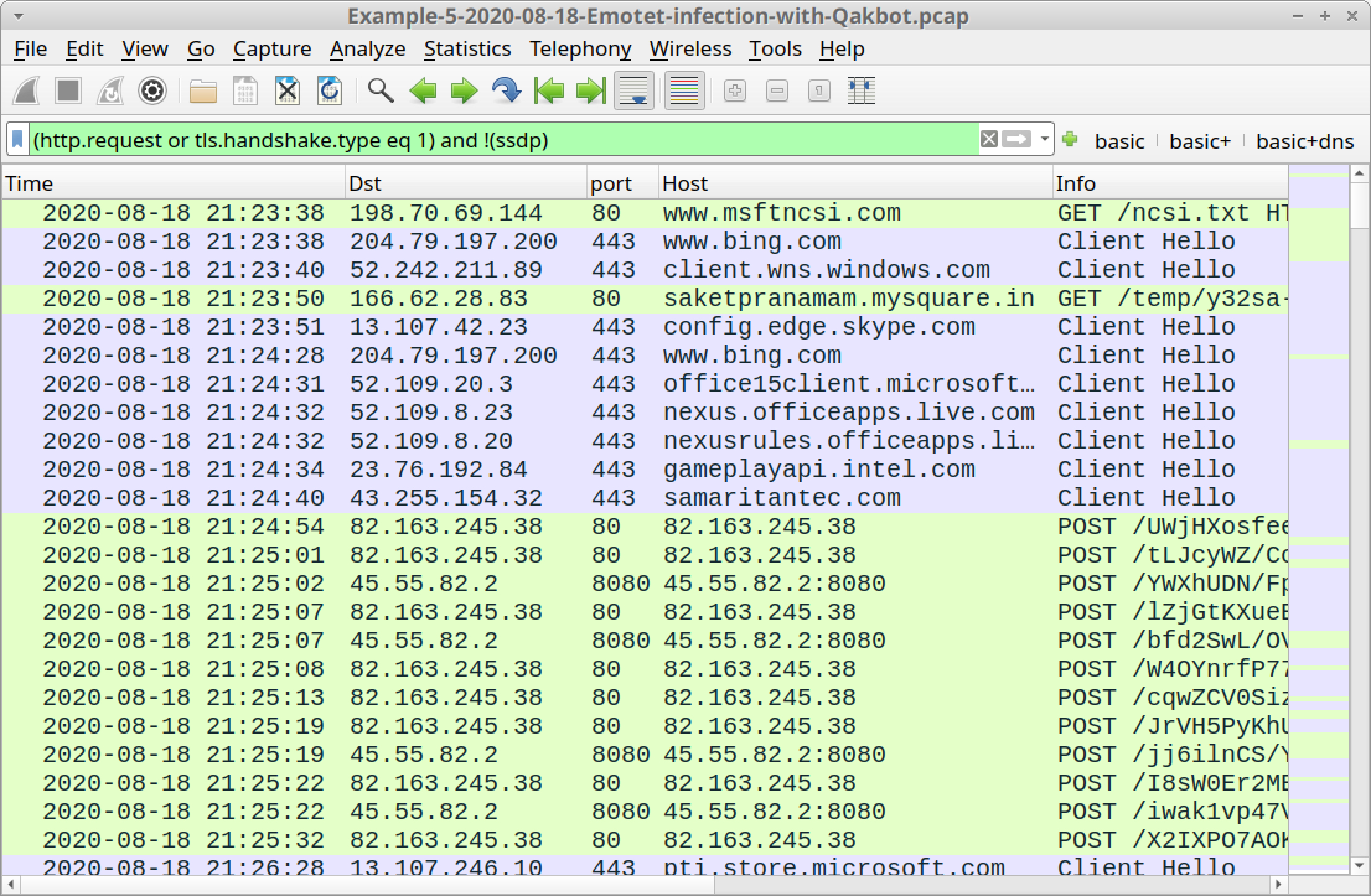

Open Example-5-2020-08-18-Emotet-infection-with-Qakbot.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 30.

In our fifth pcap, an Emotet Word document was retrieved from saketpranamam.mysquare[.]in at 21:23:50 UTC, which matches a URL reported as hosting an Emotet Word document on the same date. Export this Word document from the pcap using File --> Export Objects --> HTTP, as discussed in our previous examples.

The SHA256 hash for this extracted Word document is:

- c7f429dde8986a1b2fc51a9b3f4a78a92311677a01790682120ab603fd3c2fcb

We also see HTTPS traffic to samaritantec[.]com at 21:24:40 UTC. This domain was reported as hosting an Emotet binary on the same date.

As in our previous examples, you should find the same two types of HTTP POST requests associated with Emotet C2 traffic.

Additionally, this pcap contains indicators of a Qakbot infection. Use your basic web filter and scroll down to find Qakbot traffic, as shown in Figure 31.

We’ve reviewed Qakbot in our previous Wireshark tutorial on examining Qakbot infections, but here is a quick refresher. The following are common indicators for Qakbot:

- HTTPS traffic over standard and non-standard TCP ports for HTTPS.

- Certificate data for Qakbot HTTPS traffic has unusual values for the issuer fields, and the certificate is not issued by an authority based in the United States.

- TCP traffic over TCP port 65400.

- Prior to late November 2020, Qakbot commonly generated HTTPS traffic to cdn.speedof[.]me.

- Prior to late November 2020, Qakbot commonly generated HTTP GET requests to a.strandsglobal[.]com.

We can easily find these indicators by using the following Wireshark filters:

- tls.handshake.type eq 11 and !(x509sat.CountryName == US)

- tcp.port eq 65400

- tls.handshake.extensions_server_name contains speedof

- http.host contains strandsglobal

Figures 32-35 show the results from each of the above filters.

In Figure 32, the results of our first filter show several frames in the column display for traffic from 71.80.66[.]107. Search through the frame details and find unusual certificate issuer data, as shown above.

In the above image, we find a single TCP stream of Qakbot traffic over TCP port 65400. This stream contains the public IP address and a botnet identification string for the Qakbot-infected Windows host.

![Figure 34. Filtering for traffic to cdn.speedof[.]me, which is not inherently malicious, but a connectivity check caused by Qakbot prior to late November 2020.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/word-image-63.jpeg)

![Figure 35. Filtering for traffic to a.stransglobal[.]com, typically generated by Qakbot prior to late November 2020.](https://unit42.paloaltonetworks.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/word-image-64.jpeg)

Conclusion

This tutorial reviewed how to identify Emotet activity from pcaps of its infection traffic. We reviewed five recent pcaps and found similarities in HTTP POST requests caused by Emotet C2 traffic. The patterns are fairly unique and can be used to identify an Emotet infection within your network. We also reviewed other post-infection activities associated with Emotet, such as spambot traffic and different families of malware dropped on an infected host.

This knowledge can help security professionals better detect and catch an Emotet infection when reviewing suspicious network activity.

For more help with Wireshark, see our previous tutorials:

- Changing Your Column Display

- Display Filter Expressions

- Identifying Hosts and Users

- Exporting Objects from a Pcap

- Examining Trickbot Infections

- Examining Ursnif Infections

- Examining Qakbot Infections

- Decrypting HTTPS Traffic

- Examining Dridex Infection Traffic

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42