Ursnif is banking malware sometimes referred to as Gozi or IFSB. The Ursnif family of malware has been active for years, and current samples generate distinct traffic patterns.

This tutorial reviews packet captures (pcaps) of infection Ursnif traffic using Wireshark. Understanding these traffic patterns can be critical for security professionals when detecting and investigating Ursnif infections.

This tutorial covers the following:

- Ursnif distribution methods

- Categories of Ursnif traffic

- Five examples of pcaps from Ursnif infections

Note: This tutorial assumes you have a basic knowledge of Wireshark, and it uses a customized column display shown in this tutorial. You should also have experience with Wireshark display filters as described in this additional tutorial.

Ursnif Distribution Methods

Ursnif can be distributed through web-based infection chains and malicious spam (malspam). In some cases, Ursnif is a follow-up infection caused by different malware families like Hancitor, as reported in this recent example.

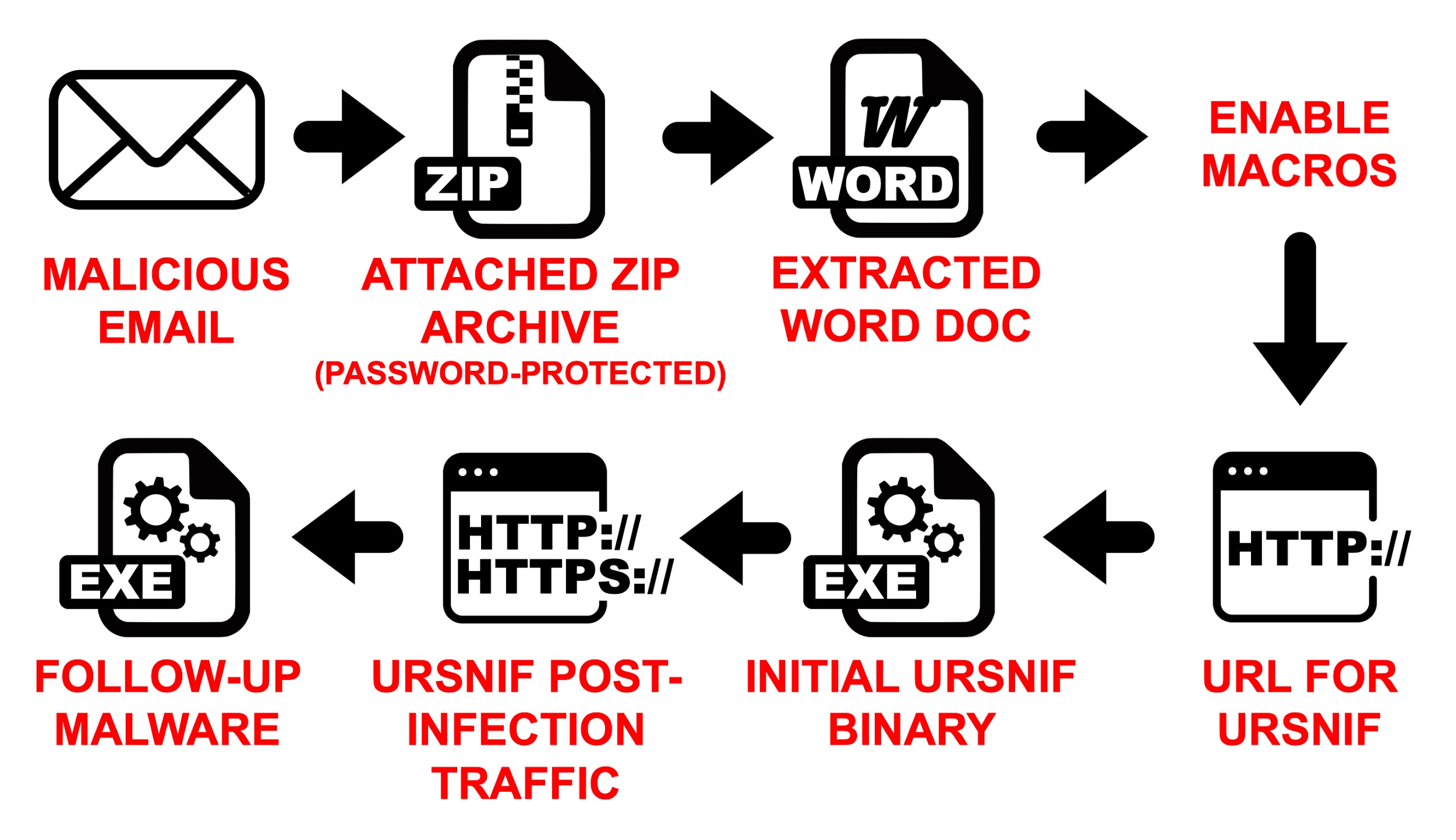

We frequently find examples of Ursnif from malspam-based distribution campaigns, such as the example in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Flowchart from one of the more common Ursnif distribution campaigns.

Figure 1. Flowchart from one of the more common Ursnif distribution campaigns.

Categories of Ursnif Traffic

This tutorial covers two categories of Ursnif infection traffic:

- Ursnif without HTTPS post-infection traffic

- Ursnif with HTTPS post-infection traffic

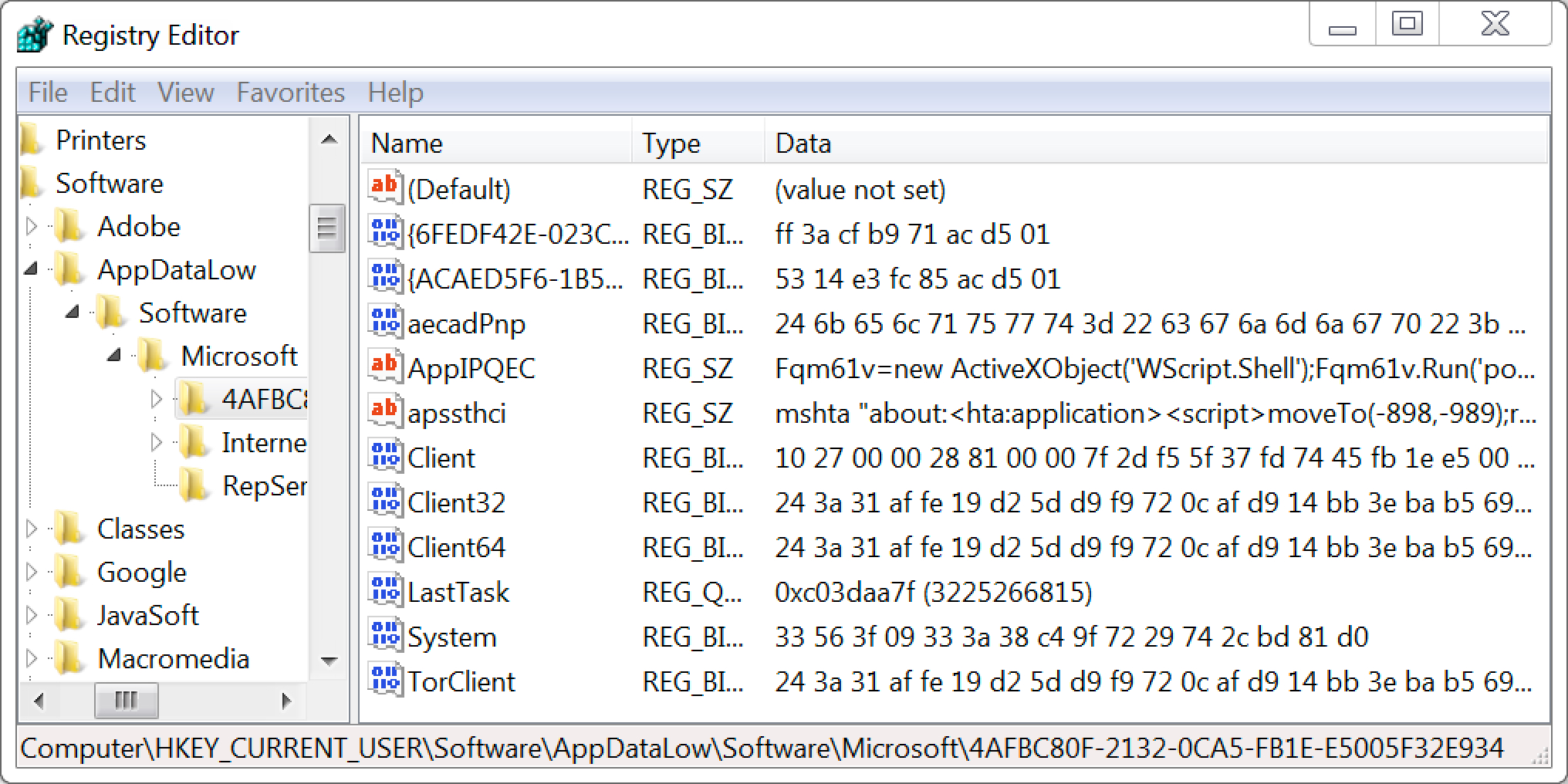

Malware samples from either of these categories create the same type of artifacts on an infected Windows host. For example, both types of Ursnif remain persistent on a Windows host by updating the Windows registry, such as the example shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Example of Windows registry updates caused by samples of Ursnif, either with or without HTTPS post-infection traffic.

Figure 2. Example of Windows registry updates caused by samples of Ursnif, either with or without HTTPS post-infection traffic.

Example 1: Ursnif without HTTPS

The first pcap for this tutorial, Ursnif-traffic-example-1.pcap, is available here. The chain of events behind this traffic was tweeted here. Example 1 has been stripped of all traffic not directly related to the Ursnif infection.

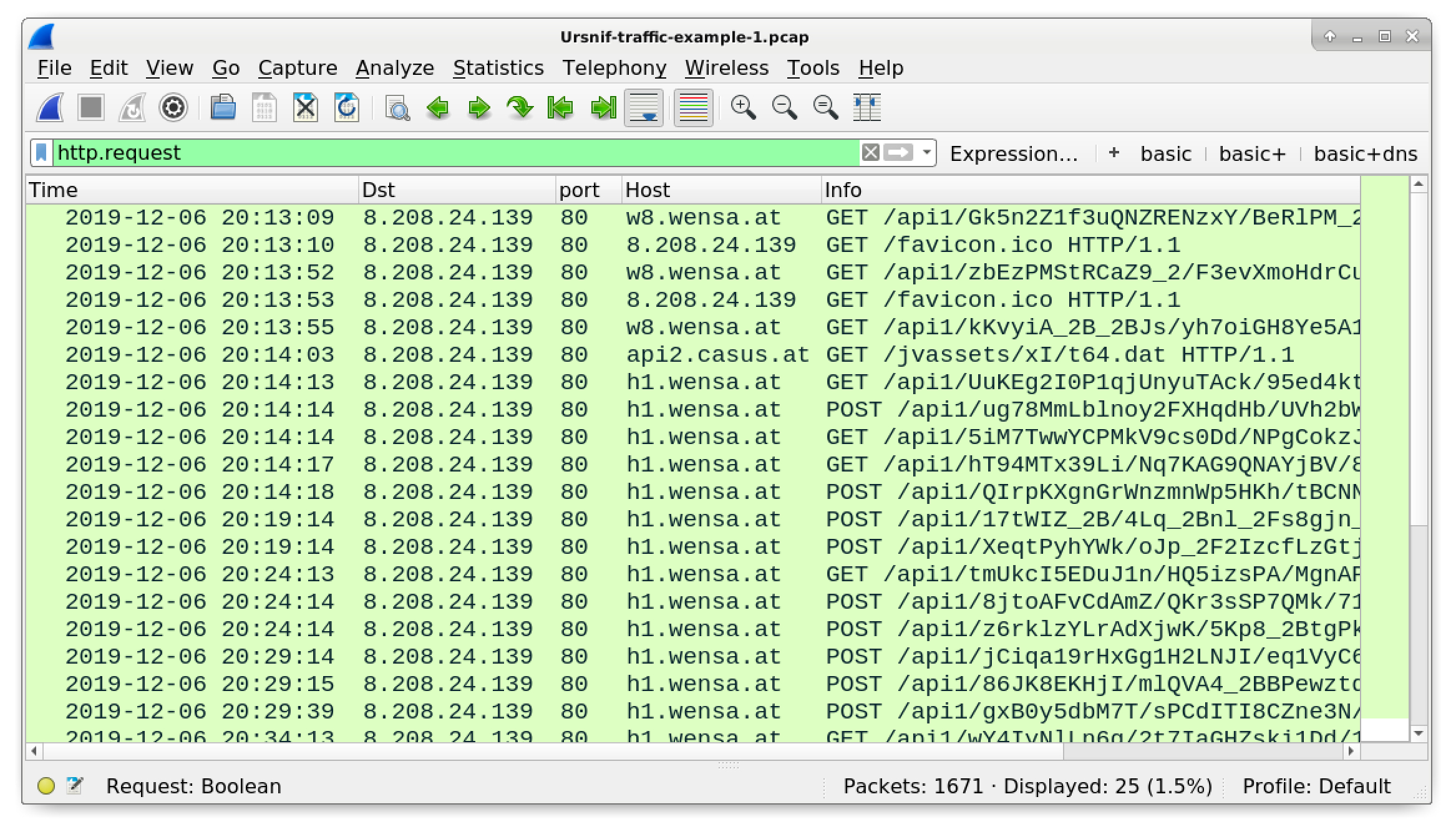

Open the pcap in Wireshark and filter on http.request as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. The pcap for example 1 filtered in Wireshark.

Figure 3. The pcap for example 1 filtered in Wireshark.

In this example, the Ursnif-infected host generates post-infection traffic to 8.208.24[.]139 using various domain names ending with .at. This category of Ursnif causes the following traffic:

- HTTP GET requests caused by the initial Ursnif binary

- HTTP GET request for follow-up data, with the URL ending in .dat

- HTTP GET and POST requests after Ursnif is persistent in the Windows registry

The following HTTP data is used during the traffic in our first example:

- Domain for initial GET requests: w8.wensa[.]at

- Request for follow-up data: hxxp://api2.casys[.]at/jvassets/xI/t64.dat

- Domain for GET and POST requests after Ursnif is persistent: h1.wensa[.]at

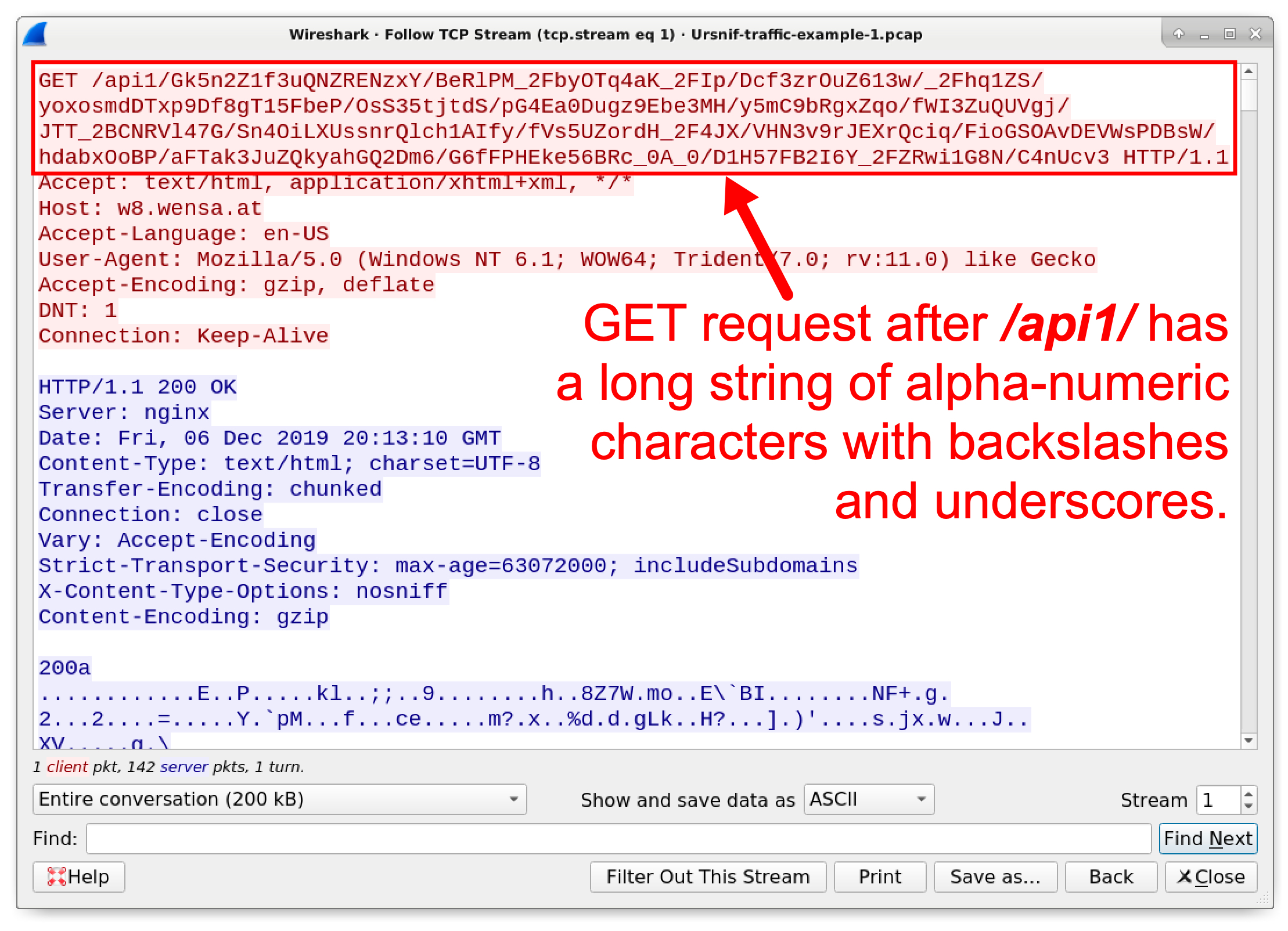

Follow the TCP stream for the very first HTTP GET request at 20:13:09 UTC. The TCP stream window shows the full URL. Note how the GET request starts with /api1/ and is followed by a long string of alpha-numeric characters with backslashes and underscores. Figure 4 highlights the GET request.

Figure 4. Example of an HTTP GET request caused by our first Ursnif example.

Figure 4. Example of an HTTP GET request caused by our first Ursnif example.

We can find the same pattern from Ursnif activity caused by a Hancitor infection on December 10,2019. The pcap is available here. Mixed with the other malware activity, this December 10th example contains the following indicators for Ursnif:

- Domain for initial GET requests: foo.fulldin[.]at

- Request for follow-up data: hxxp://one.ahah100[.]at/jvassets/o1/s64.dat

- Domain for GET and POST requests after Ursnif is persistent: api.ahah100[.]at

Note how patterns from Ursnif traffic in the December 10th example are similar to the patterns we find in example 1. These patterns are commonly seen from Ursnif samples that do not use HTTPS traffic.

Example 2: Ursnif with HTTPS

The second pcap for this tutorial, Ursnif-traffic-example-2.pcap, is available here. Like our first pcap, this one has also been stripped of any traffic not related to the Ursnif infection.

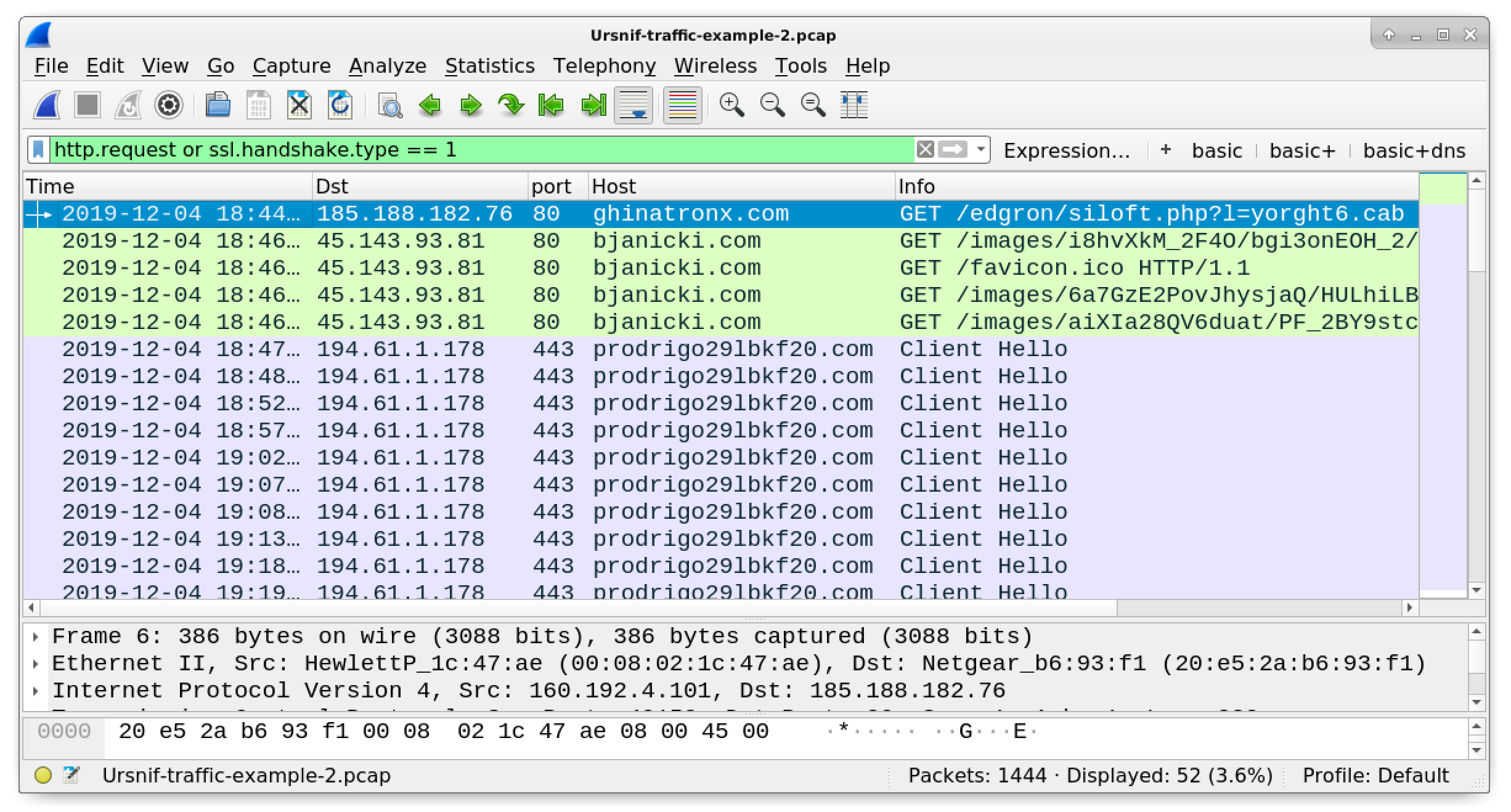

Open the pcap in Wireshark and filter on http.request or ssl.handshake.type == 1 as shown in Figure 5. If you are using Wireshark 3.0 or newer, filter on http.request or tls.handshake.type == 1 for the correct results.

Figure 5. The pcap for our second example filtered in Wireshark.

Figure 5. The pcap for our second example filtered in Wireshark.

This example has the following sequence of events:

- HTTP GET request that returns an initial Ursnif binary

- HTTP GET requests caused by the initial Ursnif binary

- HTTPS traffic after Ursnif is persistent in the Windows registry

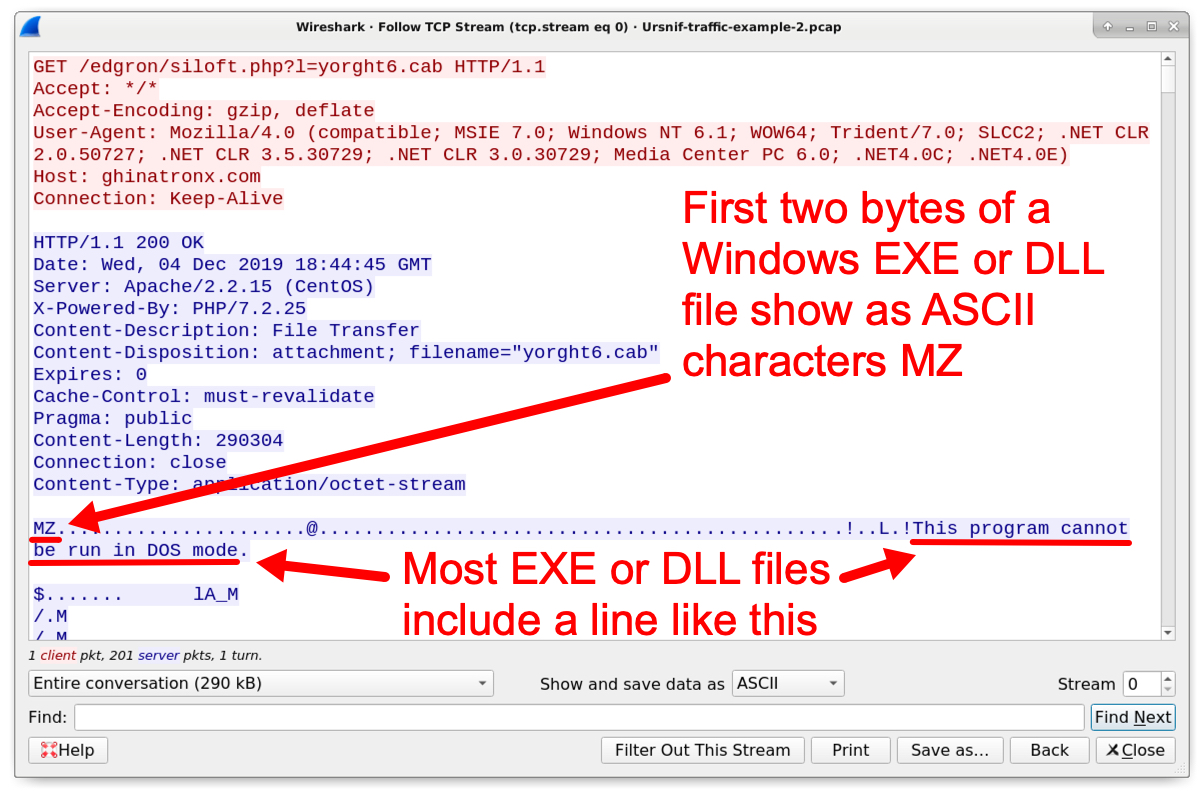

Follow the TCP stream for the first HTTP GET request to ghinatronx[.]com. This TCP stream reveals a Windows executable or DLL file as shown in Figure 6. We can export the Ursnif binary from the pcap as described in this previous tutorial.

Figure 6. The first HTTP GET request returning a binary for Ursnif.

Figure 6. The first HTTP GET request returning a binary for Ursnif.

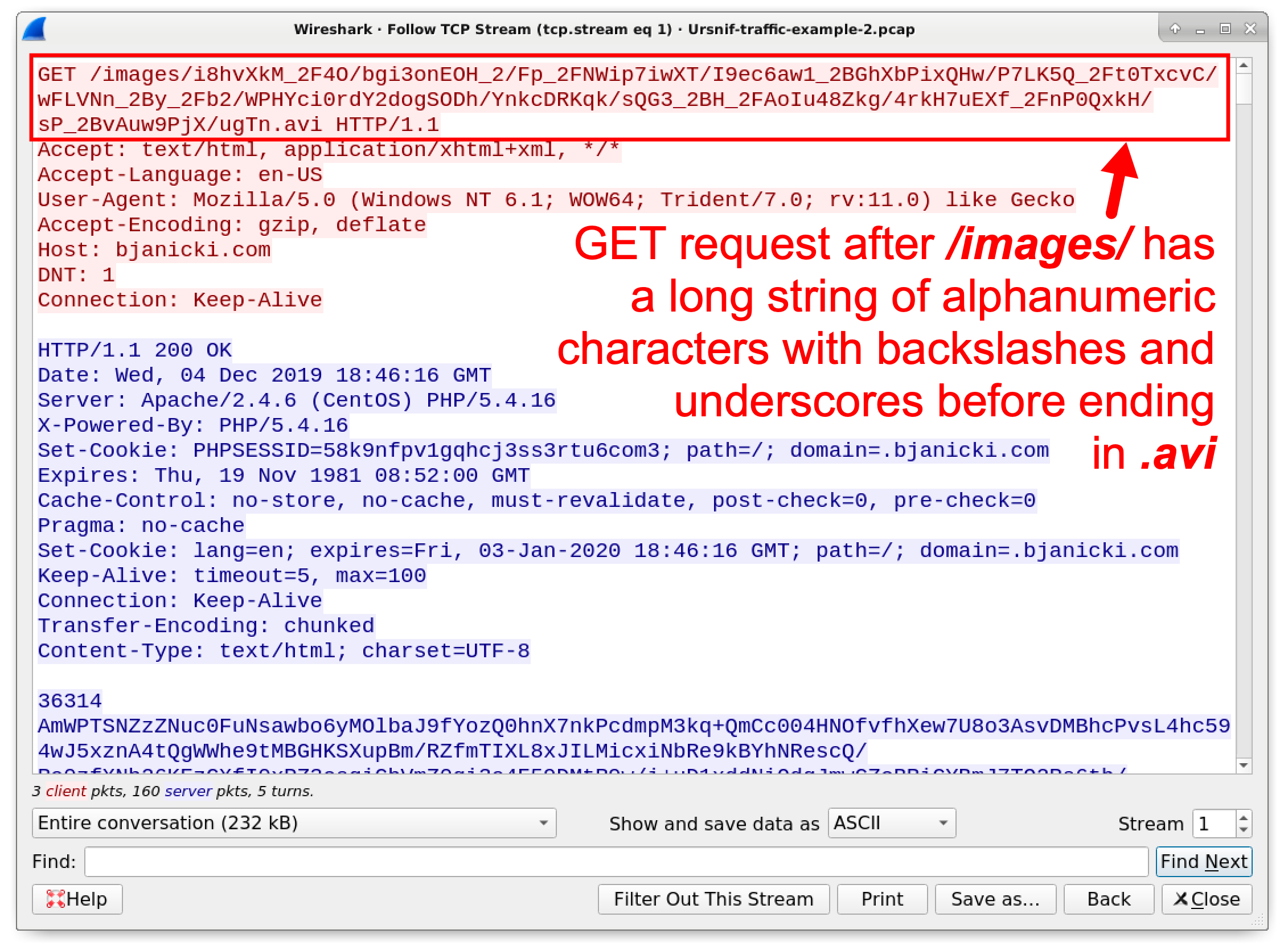

The next four HTTP requests to bjanicki[.]com were caused by the Ursnif binary. Follow the TCP stream for the first HTTP GET request to bjanicki[.]com at 18:46:21 UTC. This TCP stream shows the full URL. Note how the GET request starts with /images/ and is followed by a long string of alpha-numeric characters with backslashes and underscores before ending with .avi. This URL pattern is somewhat similar to Ursnif traffic from our first pcap. Figure 7 highlights a GET request from our second pcap.

Figure 7. Example of an HTTP GET request from our second Ursnif example.

Figure 7. Example of an HTTP GET request from our second Ursnif example.

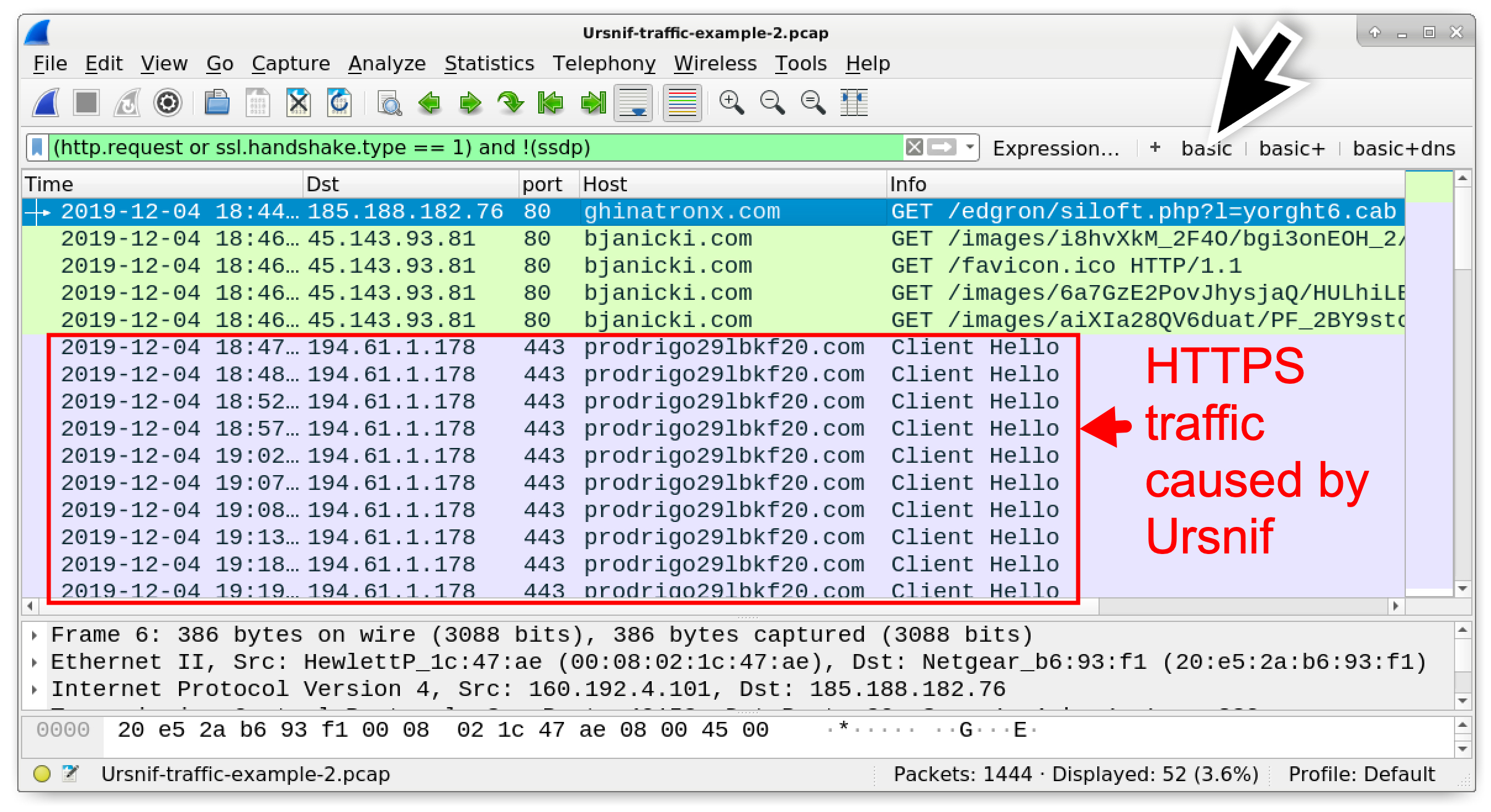

Unlike our first example, Ursnif in this second pcap generates HTTPS traffic after it becomes persistent on an infected Windows host. Use your basic web filter as described in this previous tutorial for a quick review of the HTTPS traffic. Note the HTTPS traffic to prodrigo29lbkf20[.]com as shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8. Filtering on web traffic in Wireshark, highlighting the HTTPS traffic generated by Ursnif.

Figure 8. Filtering on web traffic in Wireshark, highlighting the HTTPS traffic generated by Ursnif.

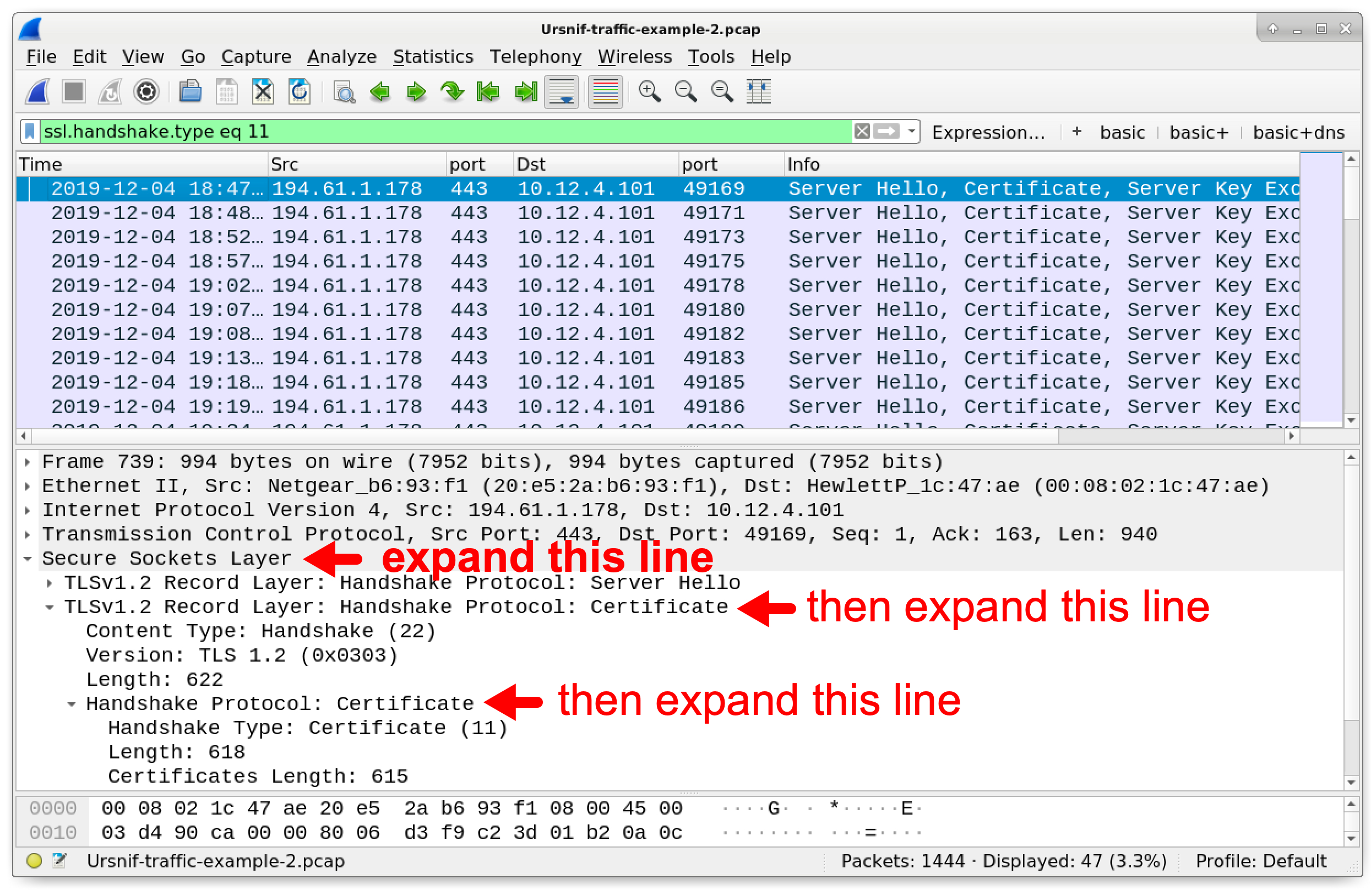

HTTPS traffic generated by this Ursnif variant reveals distinct characteristics in certificates used to establish encrypted communications. To get a closer look, filter on ssl.handshake.type == 11 (or tls.handshake.type == 11 in Wireshark 3.0 or newer). Select the first frame in the results and go to the frame details window. There we can expand lines and work our way to the certificate issuer data. Figure 9 shows how to begin.

Figure 9. Finding our way to the certificate issuer data.

Figure 9. Finding our way to the certificate issuer data.

As shown in Figure 9, we expand the line for Secure Sockets Layer in the frame details window. For Wireshark 3.0, this line shows as Transport Layer Security. Then we expand the line labeled TLSv1.2 Record Layer: Handshake Protocol: Certificate. Then we expand the line labeled Handshake Protocol: Certificate.

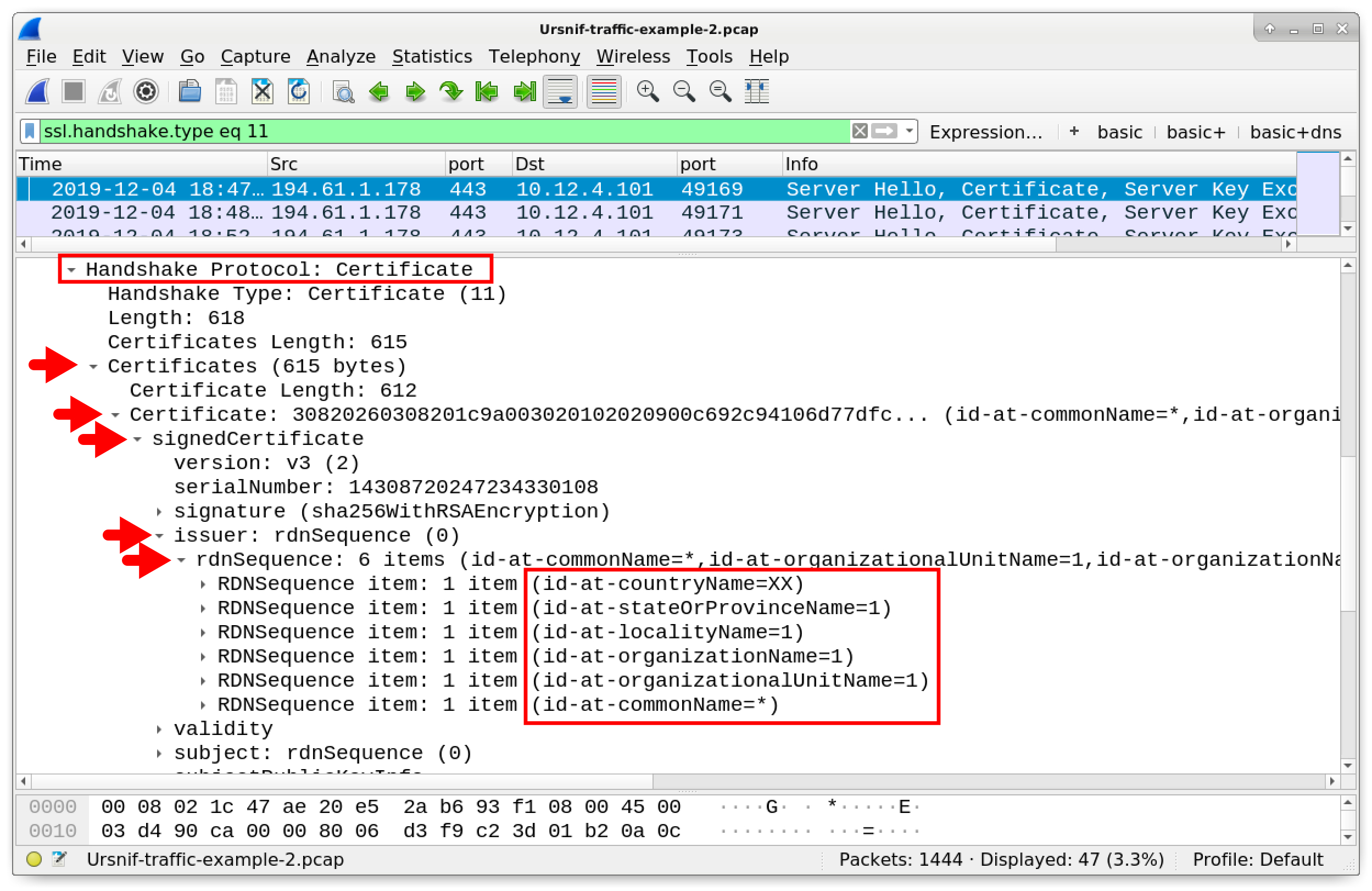

We keep expanding, until we find our way to the certificate issuer data as shown in Figure 10.

Figure 10. Certificate issuer data from HTTPS traffic caused by Ursnif.

Figure 10. Certificate issuer data from HTTPS traffic caused by Ursnif.

In Figure 10 shown under the Handshake Protocol: Certificate line, we work our way down through the following items:

- Certificates (615 bytes)

- Certificate: 30820260308201c9a003020102020900c692c94106d77dfc...

- signedCertificate

- Issuer: rdnSequence (6)

- rdnSequence: 6 items (id-at-commonName=*,id-at-organizationalUnitN...

Individual items under the rdnSequence line show properties of the certificate issuer. These reveal the following characteristics:

- countryName=XX

- stateOrProvinceName=1

- localityName=1

- organizationName=1

- organizationalUnitName=1

- commonName=*

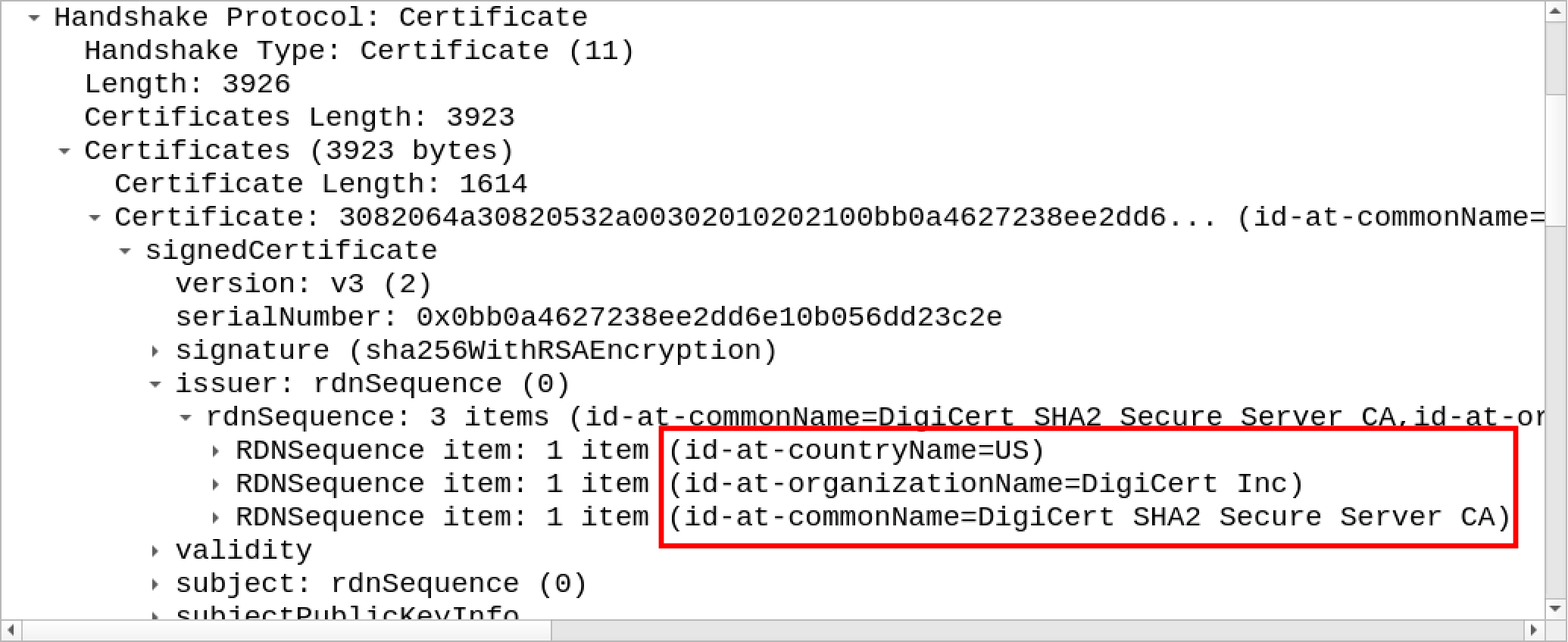

This issuer data is not valid, and these patterns are commonly seen in Ursnif infections. But what does legitimate certificate data look like? Figure 11 shows valid data from a certificate issued by DigiCert.

Figure 11. Valid certificate issuer data.

Figure 11. Valid certificate issuer data.

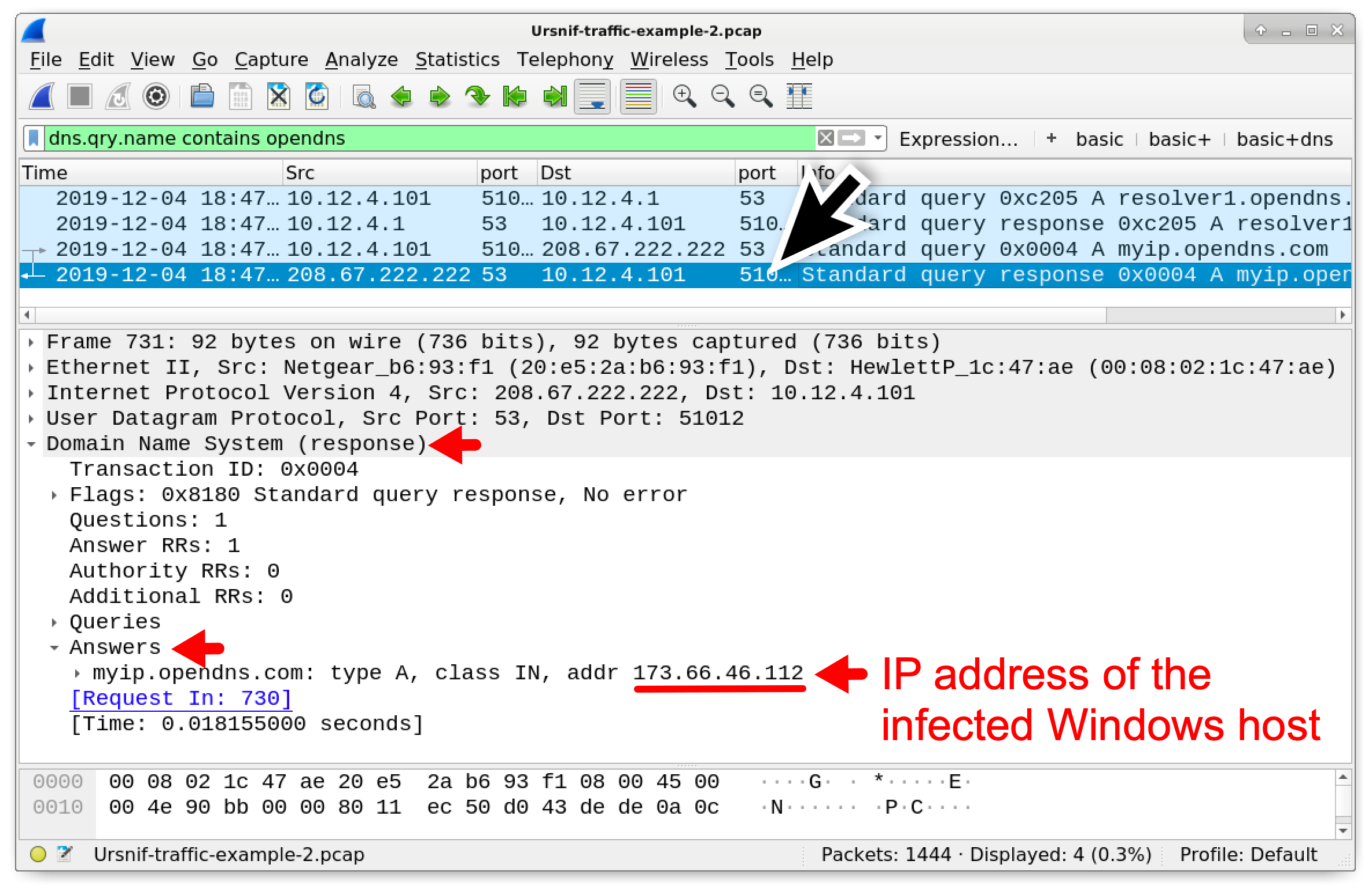

One last thing about Ursnif is the IP address check by an Ursnif-infected host. This happens over DNS using a resolver at opendns[.]com. Like other IP address identifiers, this is a legitimate service. However, these services are commonly used by malware.

To see this IP address check, filter on dns.qry.name contains opendns.com and review the results as shown in Figure 12.

Figure 12. IP address check by an Ursnif-infected Windows host.

Figure 12. IP address check by an Ursnif-infected Windows host.

As shown in Figure 12, the Window host generated a dns query for resolver1.opendns[.]com followed by a DNS query to 208.67.222[.]222 for myip.opendns[.]com. The DNS query to myip.opendns[.]com returned the public IP address of the infected Windows host.

Example 3: Ursnif with Follow-up Malware

Our third pcap, Ursnif-traffic-example-3.pcap, is available here. This pcap also has unrelated activity stripped from the traffic, but it builds on our last example. Our third pcap includes what appears to be decoy traffic, and it also includes an HTTP GET request for follow-up malware. The sequence of events is:

- HTTP GET request that returns an initial Ursnif binary

- HTTP GET requests caused by the initial Ursnif binary, including decoy URLs

- HTTPS traffic after Ursnif is persistent in the Windows registry

- HTTP GET request for follow-up malware

Use your basic web filter as described in this previous tutorial for a quick review of the web-based traffic as shown in Figure 13.

Figure 13. Filtering our third pcap for web traffic in Wireshark.

Figure 13. Filtering our third pcap for web traffic in Wireshark.

In Figure 13, the initial HTTP request to sinicaleer[.]com returned a Windows executable for Ursnif. The remaining traffic visible Figure 13 was caused by the Ursnif executable until it became persistent.

Three HTTP requests to google[.]com follow similar URL patterns as Ursnif traffic to an actual malicious domain of ghdy656262oe[.]com. These HTTP GET requests to google[.]com appear to be decoy traffic, because they do not assist the infection. HTTPS traffic over TCP port 443 to gmail[.]com and www.google[.]com also serves no direct purpose for the infection, and that activity could also be classified as decoy traffic. Figure 14 shows an example of the decoy HTTP GET requests to google[.]com.

Figure 14. Decoy HTTP GET request by the Ursnif-infected host to a Google domain.

Figure 14. Decoy HTTP GET request by the Ursnif-infected host to a Google domain.

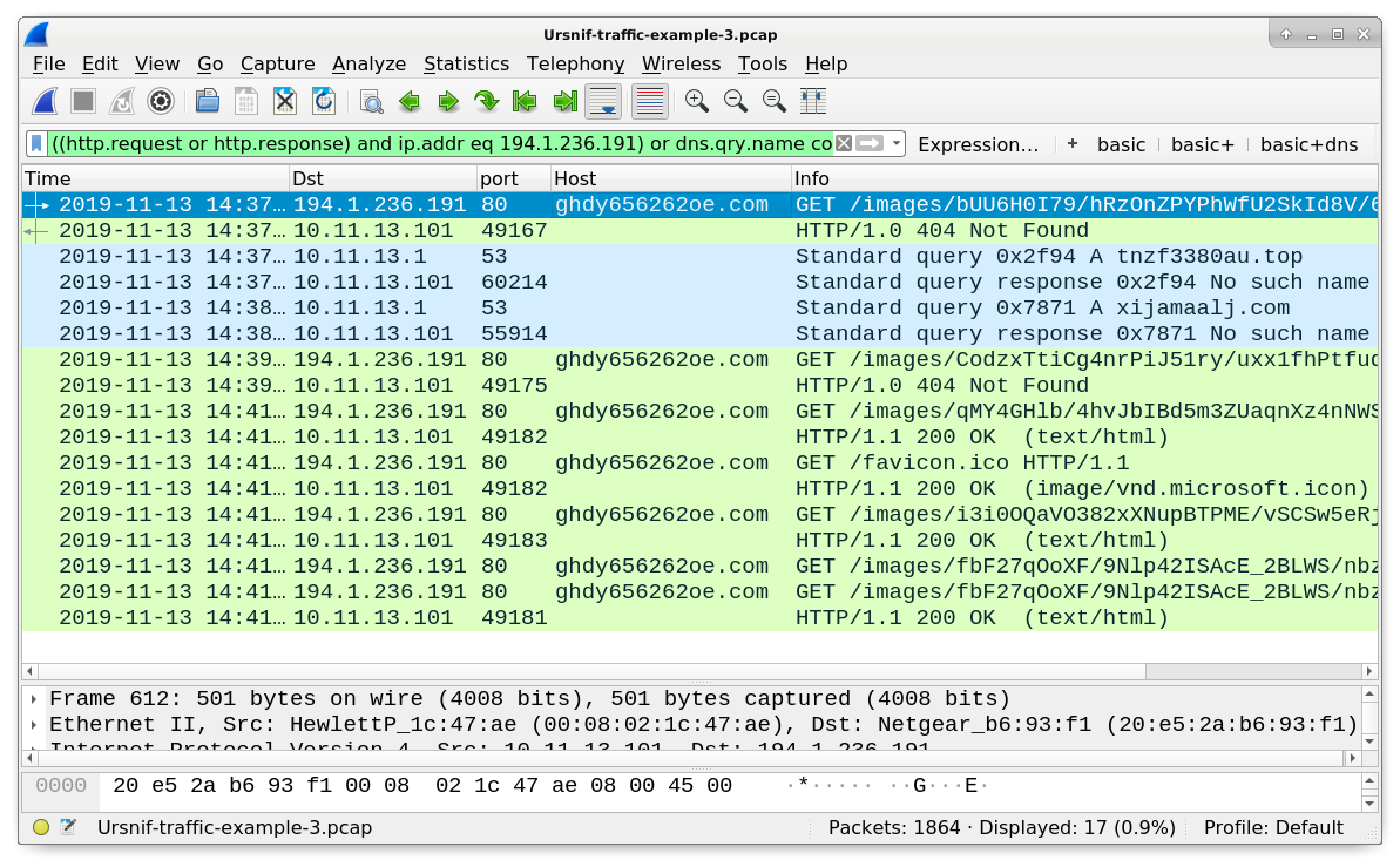

Note the HTTP traffic to ghdy656262oe[.]com. The first two GET requests to ghdy656262oe[.]com return a 404 Not Found response as shown in Figure 15. The third HTTP GET request returns a 200 OK response, and the infection continues as shown in Figure 16.

Figure 15. First two HTTP GET requests to malicious Ursnif domain return a 404 Not Found response.

Figure 15. First two HTTP GET requests to malicious Ursnif domain return a 404 Not Found response.

Figure 16. Some false starts before the Ursnif infection continues.

Figure 16. Some false starts before the Ursnif infection continues.

Since the first HTTP GET request to ghdy656262oe[.]com was not a 200 OK, the infected Windows host cycled through other malicious domains to continue the infection. These two domains are tnzf3380au[.]top and xijamaalj[.]com. However, the DNS queries for these domains returned a “No such name” in response, so the infected Windows host went back to trying ghdy656262oe[.]com.

Use the following Wireshark filter to better see this sequence of events:

((http.request or http.response) and ip.addr eq 194.1.236.191) or dns.qry.name contains tnzf3380au or dns.qry.name contains xijamaalj

The results should appear similar to the column display in Figure 17.

Figure 17. Filtering to show how the infected Windows host tries Ursnif-related domains before it hits a 200 OK in HTTP traffic.

Figure 17. Filtering to show how the infected Windows host tries Ursnif-related domains before it hits a 200 OK in HTTP traffic.

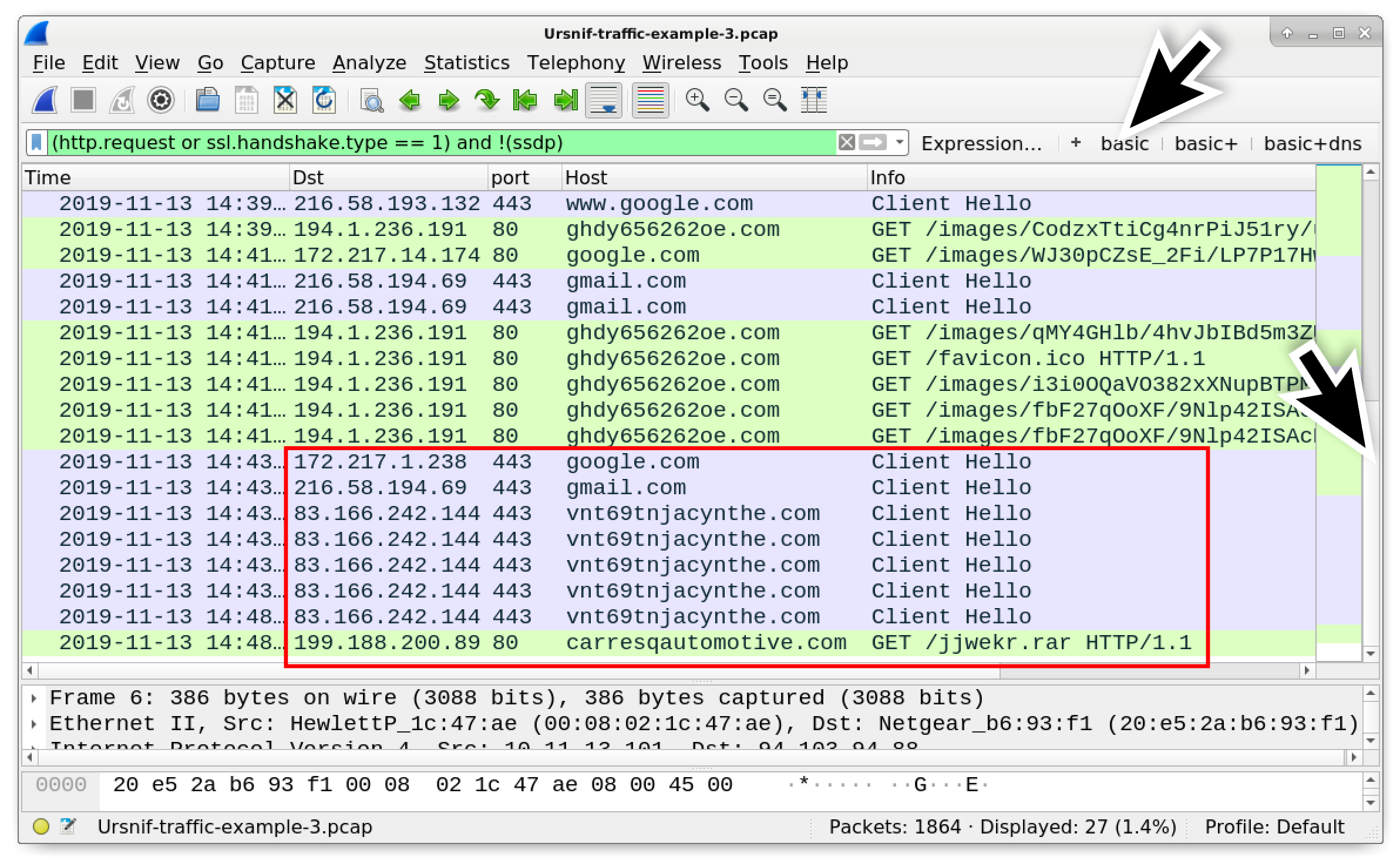

To review the rest of the infection, use your basic web filter and scroll to the end of the results. Figure 18 shows the post-infection traffic after Ursnif becomes persistent.

Figure 18. Post-infection traffic after Ursnif becomes persistent on the victim’s Windows host.

Figure 18. Post-infection traffic after Ursnif becomes persistent on the victim’s Windows host.

In Figure 18, after five HTTP GET requests to ghdy656262oe[.]com, we find traffic generated by the infected Windows host after Ursnif becomes persistent. This includes HTTPS traffic to google[.]com and gmail[.]com.

Traffic to vnt69tnjacynthe[.]com should have the same type of certificate issuer data we witnessed in our second pcap. But this traffic includes an HTTP GET request to carresqautomotive[.]com ending with .rar.

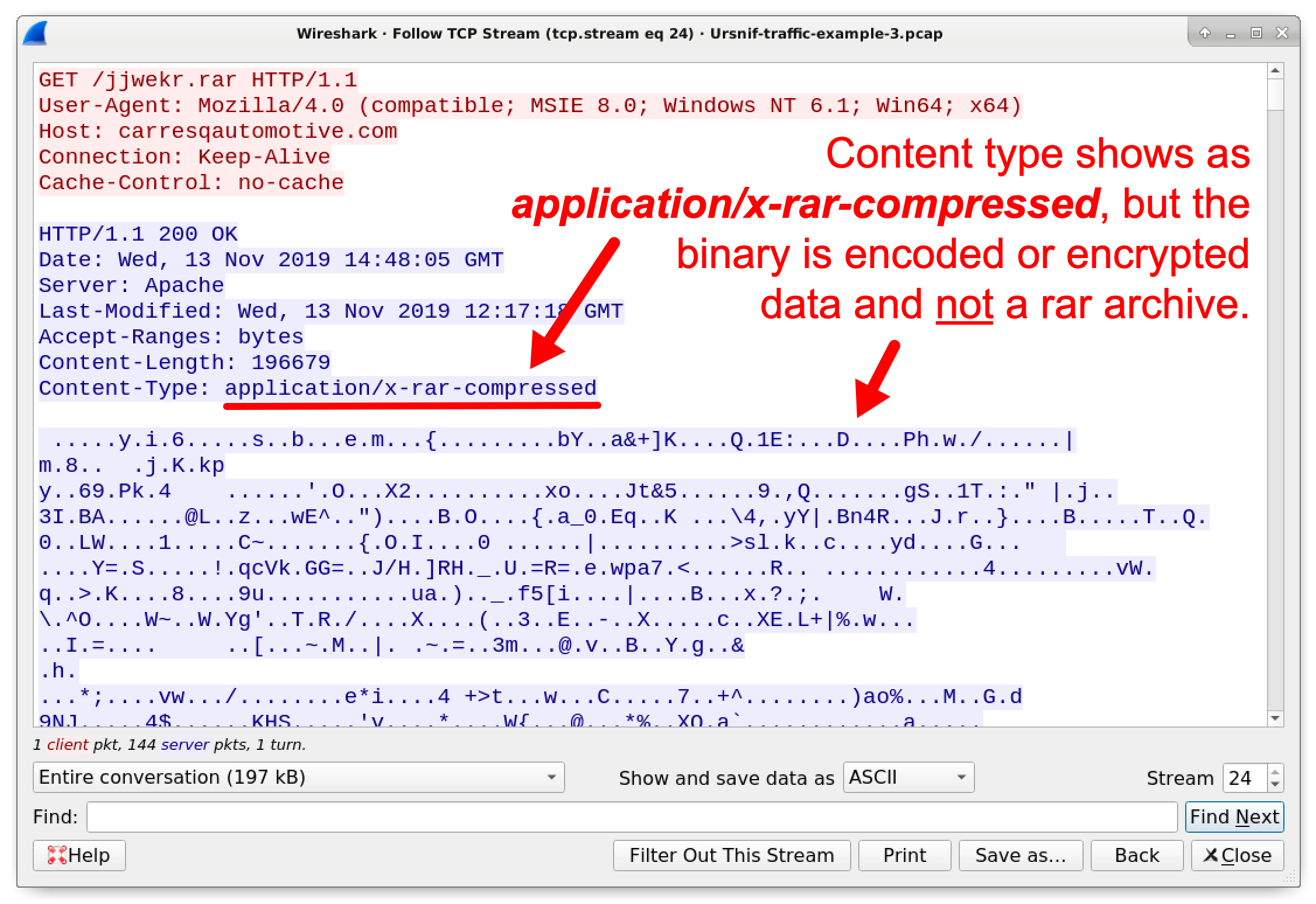

This URL ending in .rar returned follow-up malware. However, this follow-up malware is encoded or otherwise encrypted when sent over the network. The binary decoded on the infected Windows host, which is not seen in the infection traffic. Follow the TCP stream for the HTTP GET request to carresqautomotive[.]com, and you should see the same data as shown in Figure 19.

Figure 19. Follow-up malware sent to an Ursnif-infected Windows host.

Figure 19. Follow-up malware sent to an Ursnif-infected Windows host.

This data is encrypted, so we cannot export a copy of the follow-up malware from the pcap. Therefore, we must rely on other post-infection traffic to determine what type of malware was sent to the Ursnif-infected host.

We have seen various types of follow-up malware from Ursnif infections, including Dridex, IcedID, Nymain, Pushdo, and Trickbot.

Our next example is an Ursnif infection with Dridex as the follow-up malware.

Example 4: Ursnif Infection with Dridex

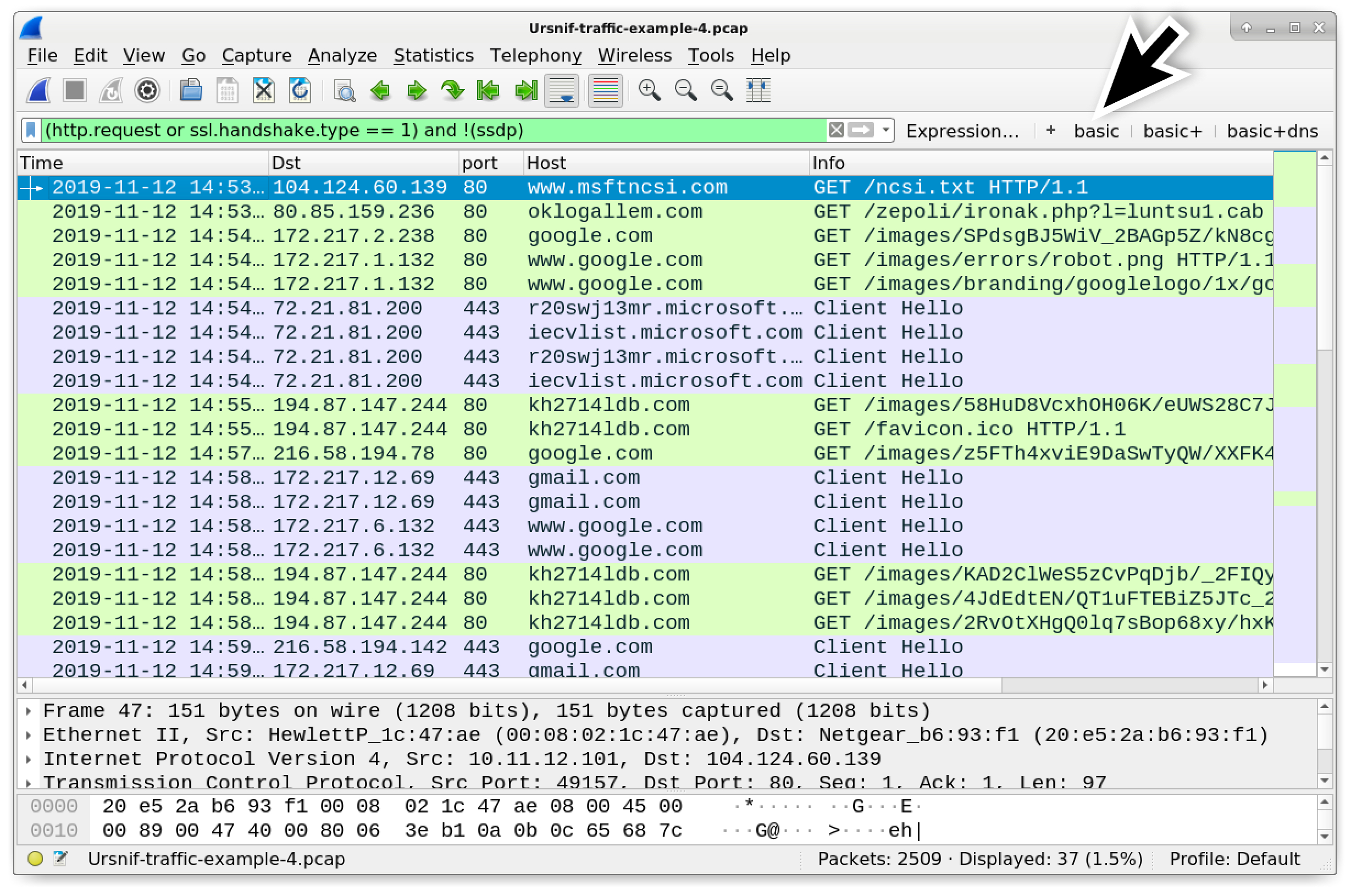

Our fourth pcap, Ursnif-traffic-example-4.pcap, is available here. Unlike our first three examples, this pcap does not have unrelated activity stripped from the traffic.

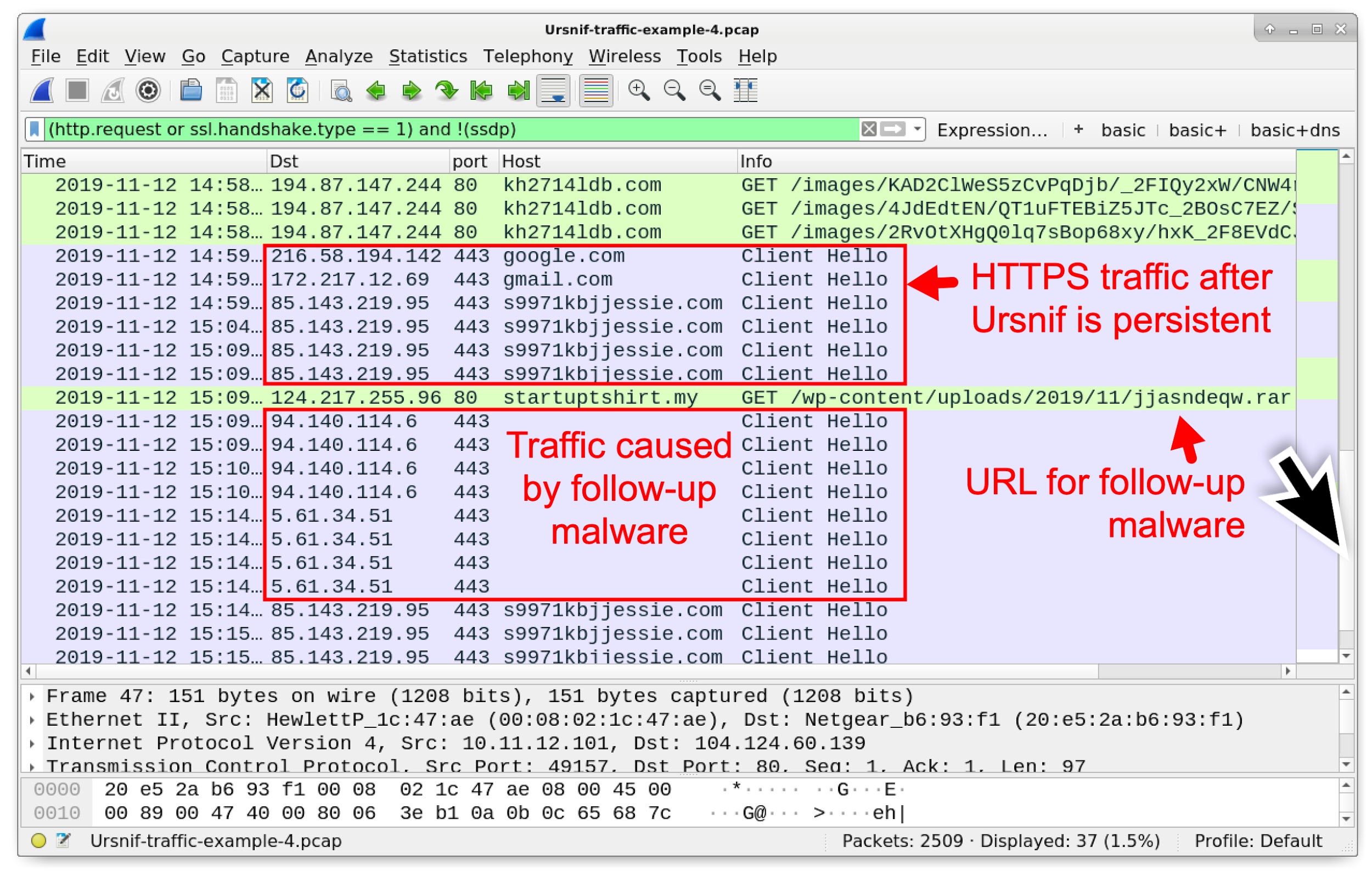

Use your basic web filter to get a better idea of the traffic. Your results should appear similar to Figure 20.

Figure 20. Traffic from our fourth pcap filtered in Wireshark.

Figure 20. Traffic from our fourth pcap filtered in Wireshark.

This pcap has the same sequence of events as our previous example, but it adds post-infection activity from the follow-up malware:

- HTTP GET request that returns an initial Ursnif binary

- HTTP GET requests caused by the initial Ursnif binary, including decoy URLs

- HTTPS traffic after Ursnif is persistent in the Windows registry

- HTTP GET request for follow-up malware

- Post-infection activity from the follow-up malware

In this fourth example, the HTTP GET request for an initial Ursnif binary is to oklogallem[.]com. Ursnif causes HTTP GET requests to kh2714ldb[.]com before the infection becomes persistent.

Figure 21 shows activity after Ursnif is persistent, where Ursnif causes HTTPS traffic to s9971kbjjessie[.]com. We then see an HTTP GET request to startuptshirt[.]my for the follow-up malware. Finally we find post-infection traffic caused by the follow-up malware.

Figure 21. Activity from the infection after Ursnif is persistent.

Figure 21. Activity from the infection after Ursnif is persistent.

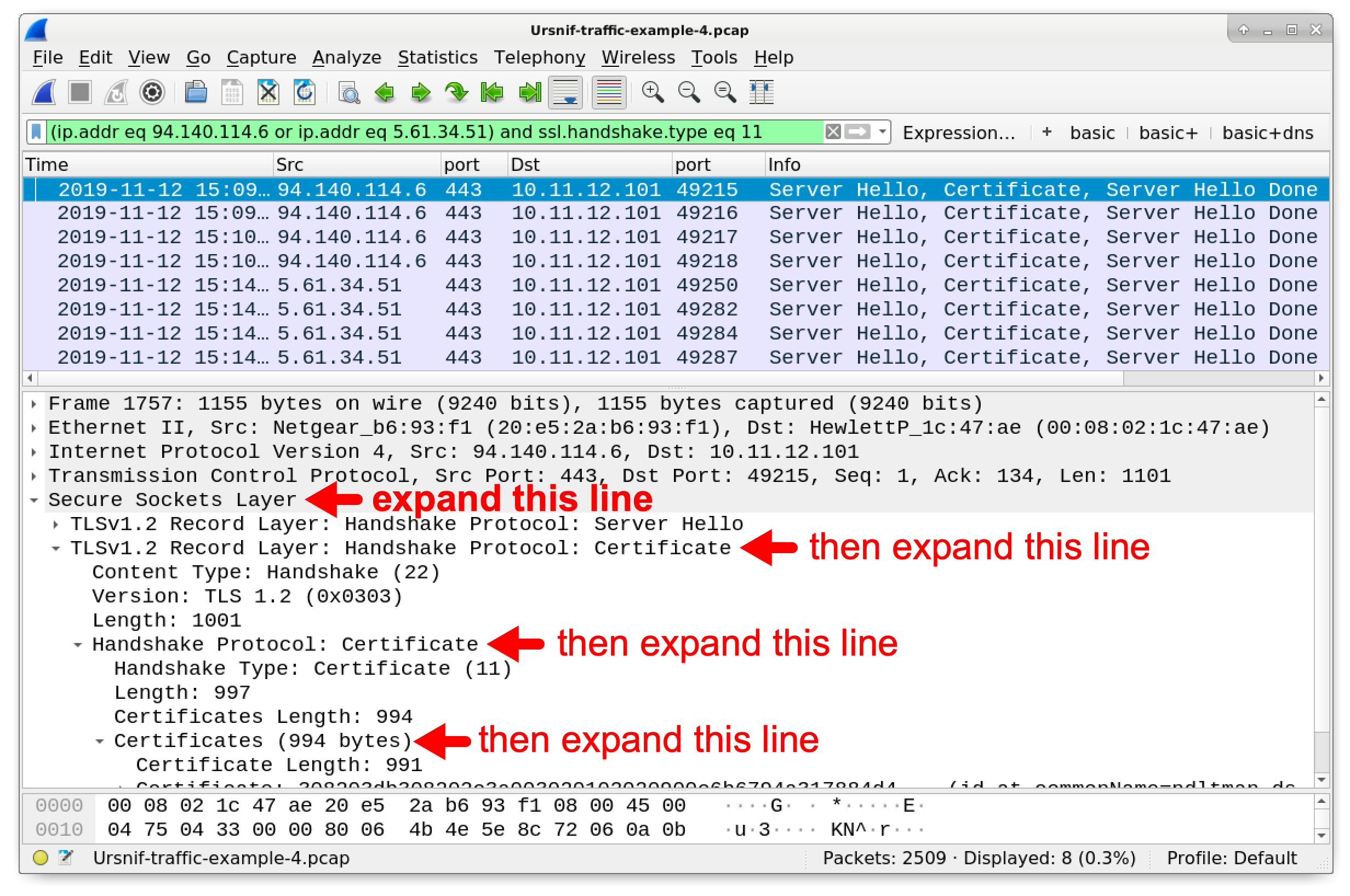

Our fourth example follows the same infection patterns as our third pcap, but now we also have HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic to 94.140.114[.]6 and 5.61.34[.]51 without any associated domain name. This is Dridex post-infection traffic.

Certificate issuer data for Dridex is different than certificate issuer data for Ursnif. Use the following filter to review the Dridex certificate data in our fourth pcap:

(ip.addr eq 94.140.114.6 or ip.addr eq 5.61.34.51) and ssl.handshake.type eq 11

Note: if you are using Wireshark 3.0 or newer, use tls.handshake.type instead of ssl.handshake.type.

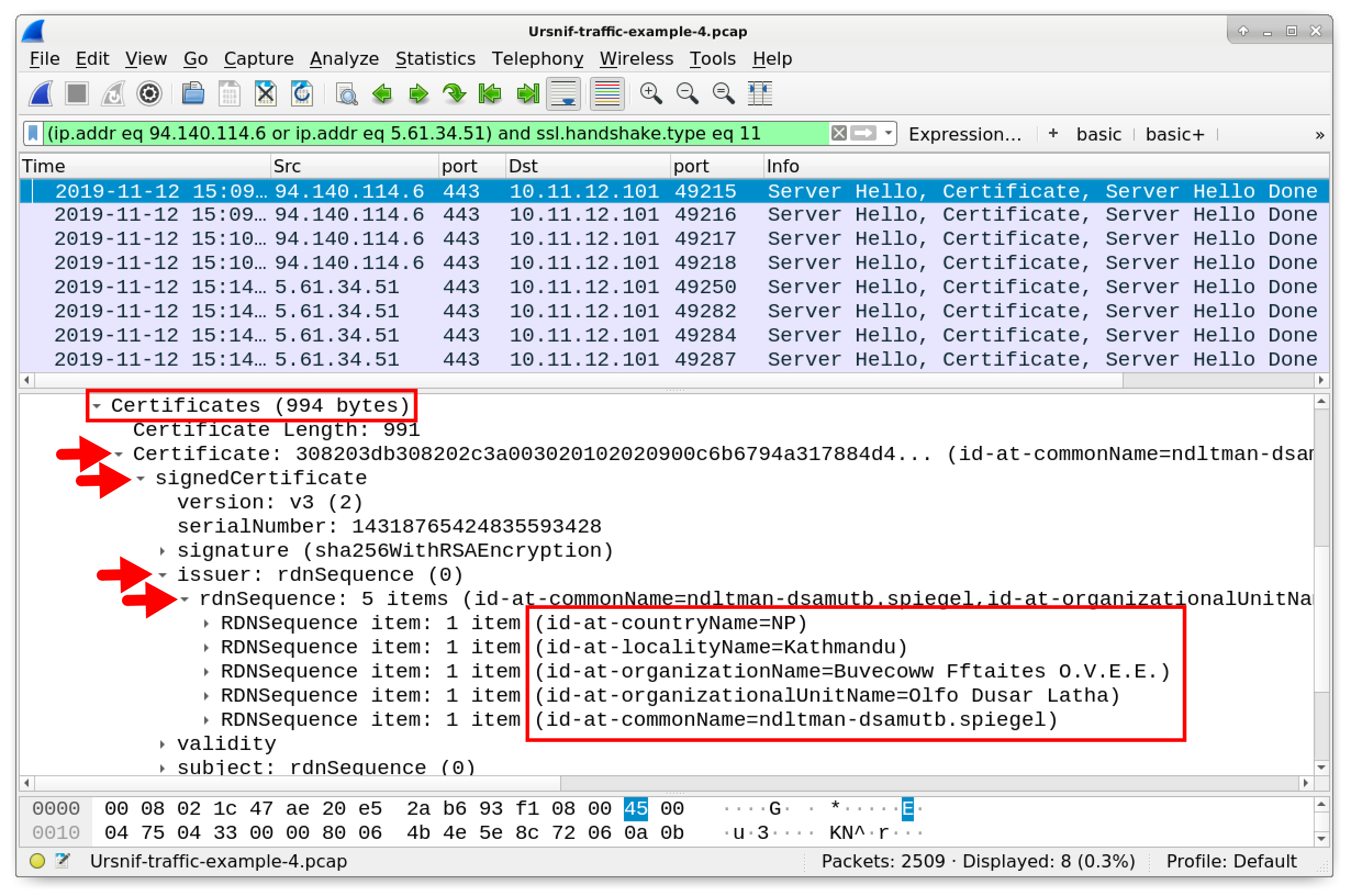

Select the first frame in the results, go to the frame details window, and expand the certificate-related lines as shown by our second example in Figures 9 and 10. Examining certificate issuer data from our fourth pcap should look similar to Figures 22 and 23.

Figure 22. Working our way to the certificate issuer data in the Dridex traffic.

Figure 22. Working our way to the certificate issuer data in the Dridex traffic.

Figure 23. Reaching the certificate issuer data from one of the Dridex IP addresses.

Figure 23. Reaching the certificate issuer data from one of the Dridex IP addresses.

Under the rdnSequence line, we find properties of the certificate issuer. Certificate issuer characteristics for HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic at 94.140.114[.]6 follows:

- countryName=NP

- localityName=Kathmandu

- organizationName=Buvecoww Fftaites O.V.E.E.

- organizationalUnitName=Olfo Dusar Latha

- commonName=ndltman-dsamutb.spiegel

Certificate issuer data is different for 5.61.34[.]51, but it follows a similar style:

- countryName=MU

- localityName=Port Louis

- organizationName=Ppoffi Sourinop Cooperative

- organizationalUnitName=ipeepstha and thicioi

- commonName=plledsaprell.Byargt9wailen.voting

This type of issuer data is commonly seen for Dridex post-infection traffic. In our next example, you can further practice reviewing certificate issuer data for Dridex.

Example 5: Evaluation

The fifth pcap for this tutorial, Ursnif-traffic-example-5.pcap, is available here. Like our previous example, this pcap has an Ursnif infection followed by Dridex, so we can practice the skills described so far in this tutorial.

Based on what we have learned so far, open the fifth pcap in Wireshark, and answer the following questions:

- For the initial Ursnif binary, which URL returned a Windows executable file?

- After the initial Ursnif binary was sent, the infected Windows host contacted different domains for the HTTP GET requests. Which domain was the traffic successful and allowed the infection to proceed?

- What domain was used in HTTPS traffic after Ursnif became persistent on the infected Windows host?

- What URL ending in .rar was used to send follow-up malware to the infected Windows host?

- What IP addresses were used for the Dridex post-infection traffic?

Answers follow.

Q: For the initial Ursnif binary, which URL returned a Windows executable file?

A: hxxp://ritalislum[.]com/obedle/zarref.php?l=sopopf8.cab

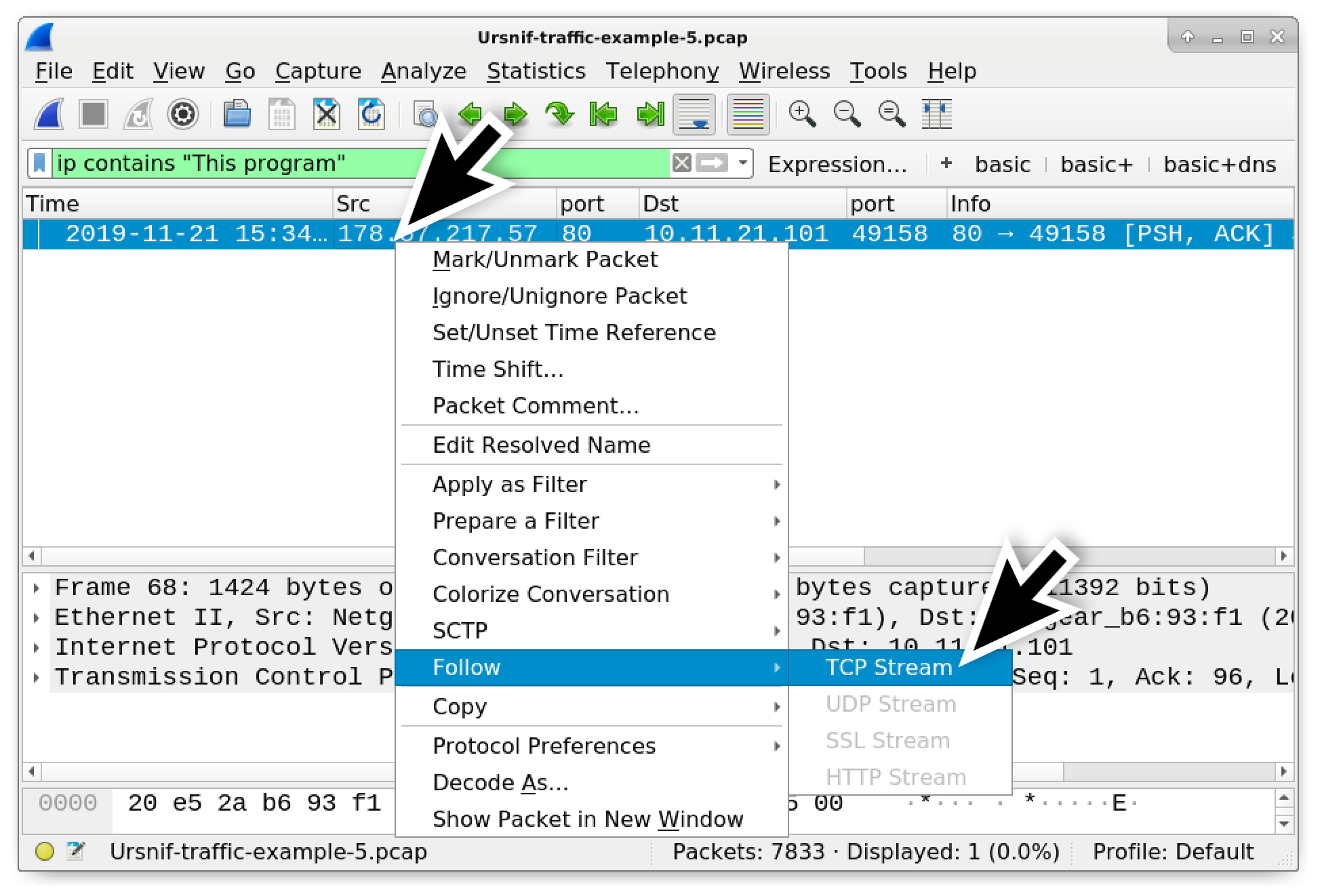

The only Windows executable file in this pcap is the initial Windows executable file for Ursnif. Use the following Wireshark search filter to quickly find this executable:

ip contains "This program"

This filter should provide only one frame in the results. Follow the TCP stream for this frame as shown in Figure 24.

Figure 24. Filtering to find a frame with the Windows executable file and following the TCP stream.

Figure 24. Filtering to find a frame with the Windows executable file and following the TCP stream.

The TCP stream window contains the domain and URL from the GET request as shown in Figure 25.

Figure 25. URL info from the TCP stream.

Figure 25. URL info from the TCP stream.

Q: After the initial Ursnif binary was sent, the infected Windows host contacted different domains for the HTTP GET requests. Which domain was the traffic successful and allowed the infection to proceed?

A: k55gaisi[.]com

Use your basic web filter for an overview of the web traffic. HTTP requests caused by this variant of Ursnif start with GET /images/ as already seen in examples two, three, and four of this tutorial. The first HTTP request to k55gaisi[.]com at 15:36 UTC is noted in Figure 26. But if you follow the TCP stream, it shows a 404 Not Found as the response.

Figure 26. Searching web traffic for HTTP GET requests caused by Ursnif.

Figure 26. Searching web traffic for HTTP GET requests caused by Ursnif.

Also shown in Figure 26, the next HTTP GET request for an Ursnif-style URL is to bon11ljgarry[.]com at 15:37 UTC. The HTTP stream for that request reveals a redirect to a URL at www.search-error[.]com.

Scroll down further, and for similar traffic to leinwqoa[.]com as noted in Figure 27.

Figure 27. Finding another Ursnif-style URL that redirects to a search error page.

Figure 27. Finding another Ursnif-style URL that redirects to a search error page.

Scroll down further to find four HTTP GET requests to k55gaisi[.]com that return 200 OK responses. From this point, the Ursnif infection proceeds, and we find no further Ursnif-style HTTP requests that start with GET /images/.

Figure 28. Finding the Ursnif-style HTTP GET requests that return a 200 OK.

Figure 28. Finding the Ursnif-style HTTP GET requests that return a 200 OK.

Q: What domain was used in HTTPS traffic after Ursnif became persistent on the infected Windows host?

A: n9maryjanef[.]com

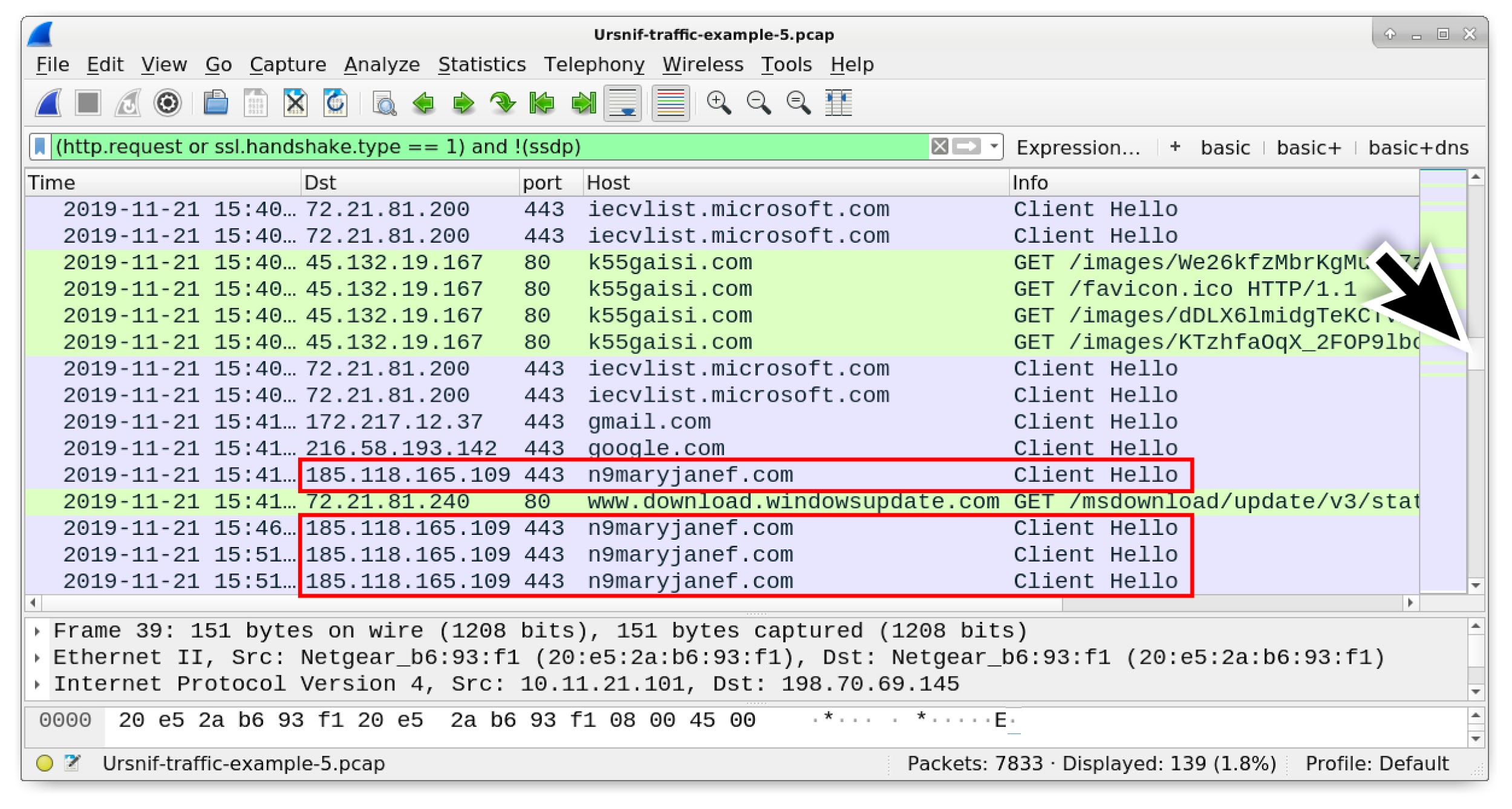

When Ursnif is persistent, we no longer see Ursnif-style HTTP requests starting with GET /images/. Instead, we find Ursnif-related HTTPS traffic. Shortly after the final Ursnif-style HTTP GET request, HTTPS traffic to n9maryjanef[.]com begins on 185.118.165[.]109 as highlighted in Figure 29. This is Ursnif traffic.

Figure 29. HTTPS traffic caused by Ursnif.

Figure 29. HTTPS traffic caused by Ursnif.

You can confirm this is Ursnif traffic by filtering on ip.addr eq 185.118.165.109 and ssl.handshake.type == 11 and reviewing the certificate issuer data. The certificate issuer data should look the same as our second example in Figure 10.

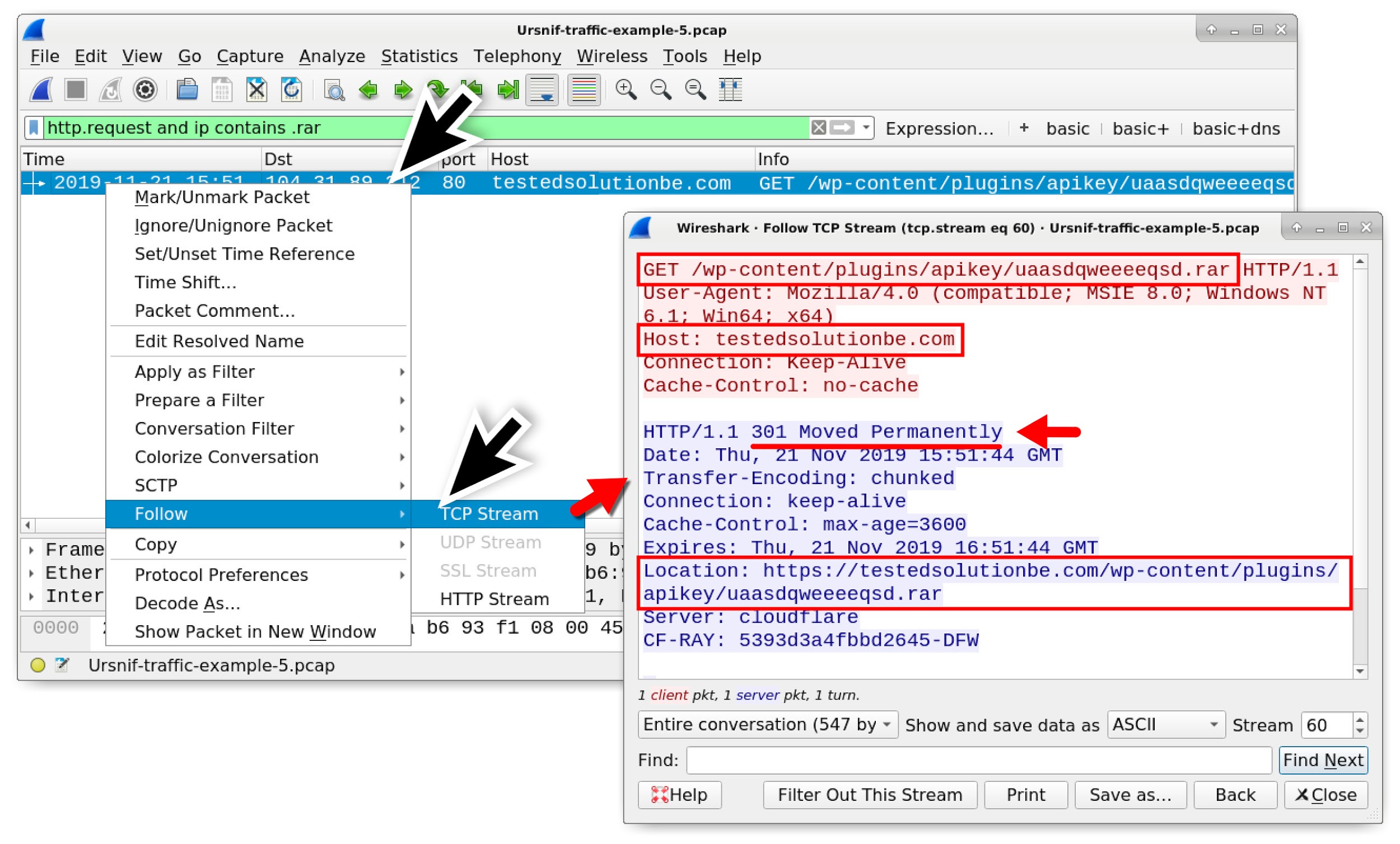

Q: What URL ending in .rar was used to send follow-up malware to the infected Windows host?

A: hxxps://testedsolutionbe[.]com/wp-content/plugins/apikey/uaasdqweeeeqsd.rar

HTTP GET requests caused by Ursnif for follow-up malware end in .rar, so use the following filter to find this URL in our pcap:

http.request and ip contains .rar

The results should be similar to what we see in Figure 30.

Figure 30. Finding the URL for follow-up malware from this Ursnif infection.

Figure 30. Finding the URL for follow-up malware from this Ursnif infection.

Notice in Figure 30 how the HTTP GET request in Figure 30 redirects to an HTTPS URL.

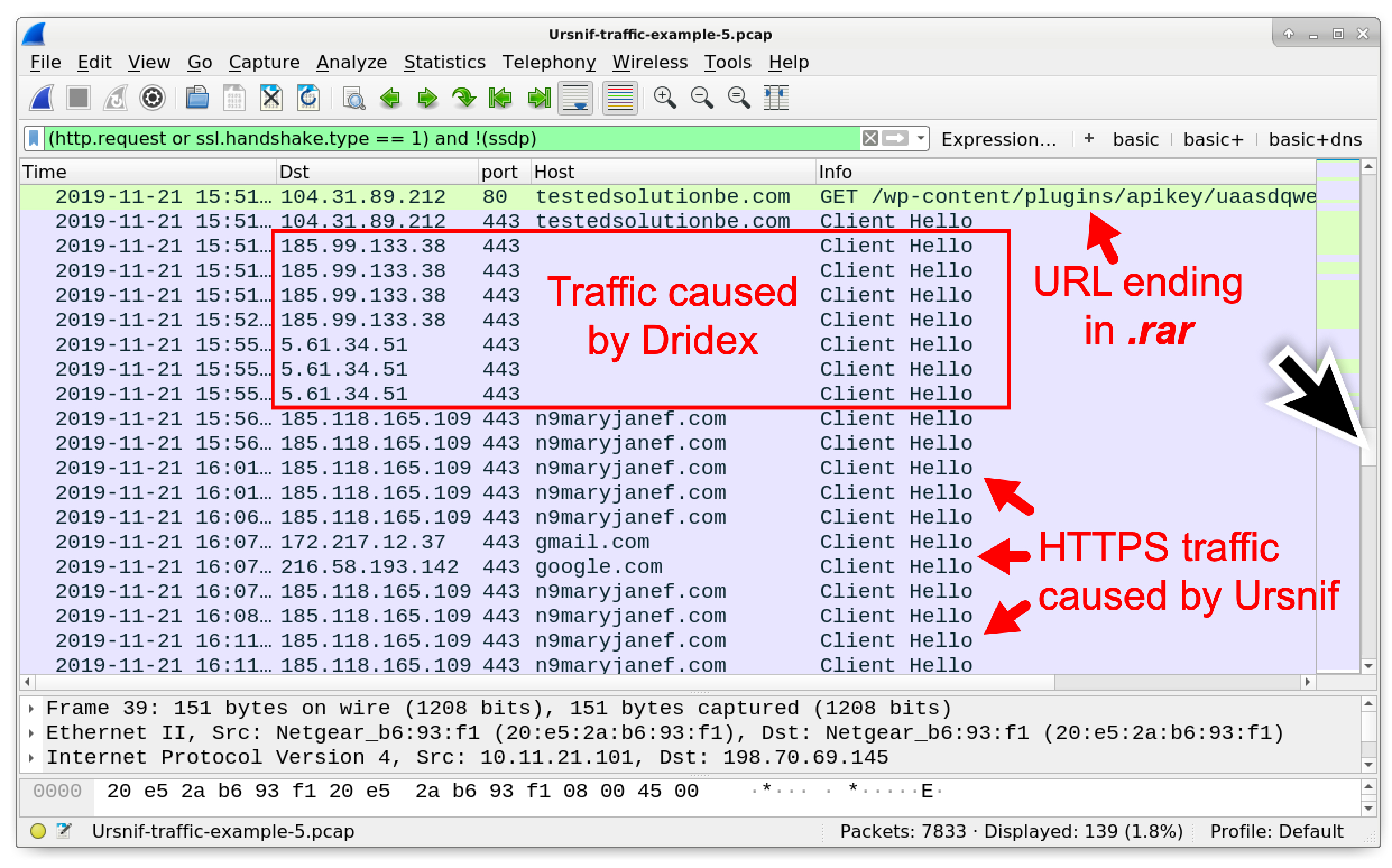

Q: What IP addresses were used for the Dridex post-infection traffic?

A: 185.99.133[.]38 and 5.61.34[.]51

One of these IP addresses is the same as Dridex in our fourth pcap, and it has the same certificate issuer data. Dridex traffic to 185.99.133[.]38 has the same style of certificate issuer data as seen in example 4. Traffic to both IP addresses does not involve a domain name.

The Dridex post-infection traffic is easy to spot in this example if we look for any HTTPS/SSL/TLS traffic without a domain after the HTTP GET request ending in .rar as shown in Figure 31.

Figure 31. Finding the Dridex traffic in our fifth pcap.

Figure 31. Finding the Dridex traffic in our fifth pcap.

Conclusion

This tutorial provided tips for examining Windows infections with Ursnif malware. More pcaps with examples of Ursnif activity can be found at malware-traffic-analysis.net.

For more help with Wireshark, see our previous tutorials:

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42