Executive Summary

As security practitioners, we spend a lot of time focusing on the threat actors and malware families that leverage the most impactful exploits or affect the highest number of victims. But what happens when a threat actor goes “low and slow” to fly under the radar? One could argue that, in that situation, the threat actor may end up having more impact than some of the more prolific threat groups.

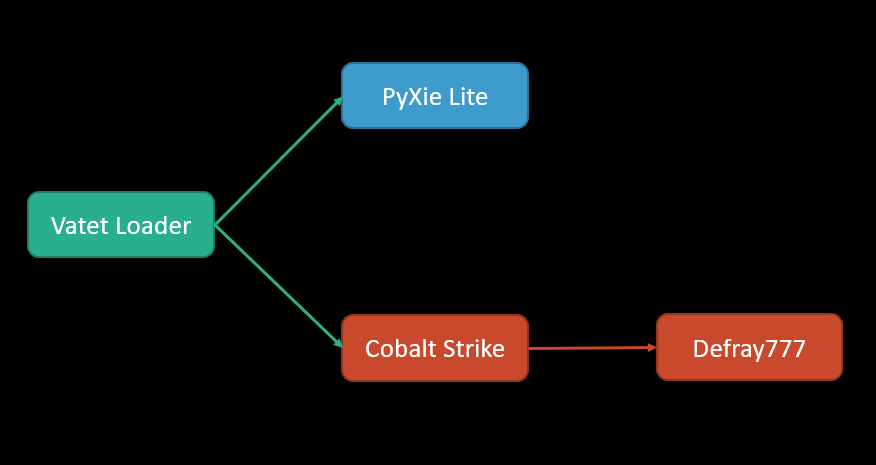

We first noticed that there may be a relationship between the Vatet loader, PyXie Remote Access Tool (RAT) and Defray777 ransomware when there were remnants and/or detections of all three in various Incident Response and Managed Threat Hunting engagements. After digging deep into each malware family, it became apparent that Vatet, PyXie and Defray777 are all associated with the same financially motivated threat group that has been operating since as early as 2018.

That threat group, sometimes referred to as PyXie by BlackBerry Cylance and GOLD DUPONT by SecureWorks, has been actively conducting successful ransomware operations that have impacted organizations in a number of sectors including healthcare, education, government and technology while remaining under the radar. This blog aims to shed light on this threat group and to disrupt their operations through awareness of their malware families and operating methodologies. In essence, we want to get them on the radar.

During our research, we discovered that this threat group has developed and maintained the Vatet loader. This loader has evolved as this threat group has taken advantage of multiple open source tools by altering the original application to execute payloads such as PyXie and/or Cobalt Strike. Next, the threat group uses a tailored version of PyXie, which we call PyXie Lite, to conduct reconnaissance and to find and exfiltrate files that are likely sensitive to the victim organization. In a number of incidents we investigated, the actors established an initial foothold into the victim's network through common banking trojans such as IcedID or Trickbot. From there, they deployed Vatet, PyXie and Cobalt Strike before executing Defray777 ransomware entirely in memory. This results in encrypted files on local drives and file shares before exiting. Additionally, the ransomware leaves no evidence of execution except for the encrypted files and ransom notes. In regard to Defray777, the group behind this malware has also ported their ransomware from Windows to Linux, something that, before Defray777, has yet to be seen in the targeted ransomware space. Before this discovery, ransomware that had the ability to impact both Windows and Linux systems was limited to cross-functional ransomware written in Java or scripting languages such as Python. With the port to Linux, Defray777 ransomware has become the first ransomware variant to have standalone executables for Windows and Linux.

With three different malware families to cover, we realize there is a lot of content to digest. We have a lot of great details on each of these, but we also realize that you may be interested in one malware family over the others, or you may just prefer to choose your own adventure. If desired, use the links below to skip to the malware family that interests you most, or to get right to the IOCs that will get you hunting for, and detecting, this threat group in action.

Table of Contents

- First Up: Vatet Loader

- Next Up: PyXie Lite

- Last, but Not Least: Defray777

- Linking Vatet, PyXie and Defray777

- Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

First Up: Vatet Loader

Vatet is a custom loader that executes XOR encoded shellcode from the local disk or a network share. The loaders are typically open source applications found on GitHub, or other repositories, that the actors modify to load their shellcode. In most cases, the payload winds up being Cobalt Strike beacons and/or stagers, but some of the more recent payloads have been an updated version of the PyXie RAT. Vatet is often a precursor to enterprise-wide ransomware attacks.

Microsoft wrote about the Vatet loader in April 2020 and said the loader had been in use as early as November 2018 for the purpose of loading Cobalt Strike into memory for execution. This loader continues to be seen in the wild using multiple versions of open source applications to load shellcode including:

| Version | First Seen |

| Recompiled Tetris game | 2019-06-28 |

| Recompiled Notepad | 2020-05-03 |

| Recompiled desktop customization app, Rainmeter | 2020-06-24 |

| Recompiled Notepad++ | 2020-09-24 |

Table 1. Vatet versions.

In our research, we have seen Vatet samples with compile times as early as 2019, although this variant has implemented several variations since then.

In the earliest versions of Vatet that we analyzed, the malicious payload was loaded via a network share using a path with the following format: \\{IP}\{EPOCHTIME}\{PAYLOAD}.dat. However, in the latest samples analyzed, the malicious payload was loaded locally from disk. Additionally, we have seen variations in the XOR keys used to decode the payload during execution time. Our research also determined that the Vatet loader has expanded its payload capabilities to load PyXie in addition to the previously seen Cobalt Strike beacons and stagers. Finally, the Vatet loaders we analyzed have evolved and begun taking steps to improve their anti-forensics capabilities by deleting malicious payloads after they have been loaded into memory for execution.

Let’s take a deeper look at Vatet using a malicious version of Rainmeter.

Inner Workings of the Vatet Loader: A Rainmeter Review

Rainmeter is a desktop customization tool that allows users to customize their desktops through the use of “skins.” During a legitimate installation, Rainmeter creates an executable, rainmeter.exe, and a corresponding DLL, rainmeter.dll. Under normal conditions, rainmeter.dll is responsible for reading configuration files and facilitating a customized desktop. Under the observed circumstances, a signed, legitimate version of rainmeter.exe and a malicious version of rainmeter.dll could be simply copied onto the victim system, then used to load and execute a Cobalt Strike beacon in memory under the context of a signed, legitimate executable.

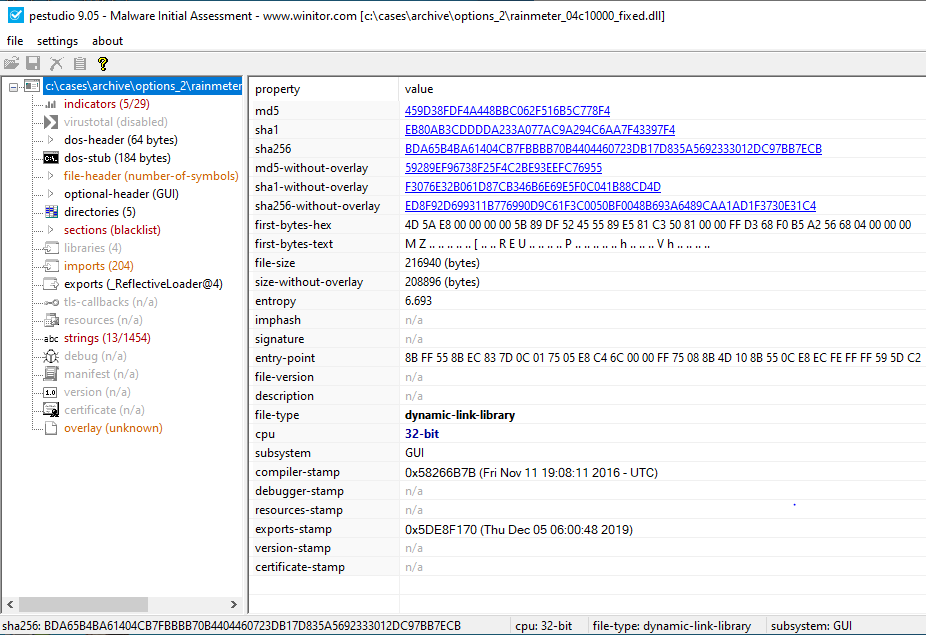

Taking a Look at the Static Properties

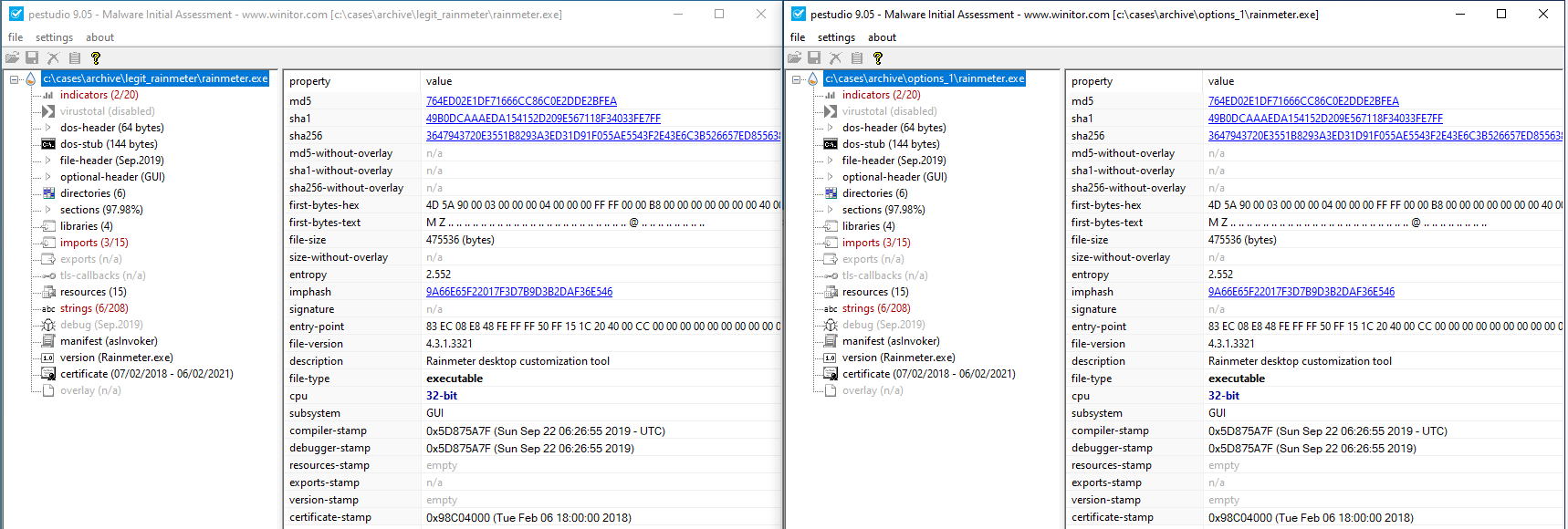

We first reviewed the suspicious rainmeter.exe and rainmeter.dll files and compared them to versions that would be installed on a system through the official September 2019 release of the Rainmeter installer, which can be found on its public GitHub page.

Reviewing rainmeter.exe did not produce many interesting findings. Examining both executables in PEStudio confirmed that the sample recovered during a ransomware scenario was the same executable generated by the standard Rainmeter installer, based on the SHA256 hash. We also verified that both executables had the same valid digital signature.

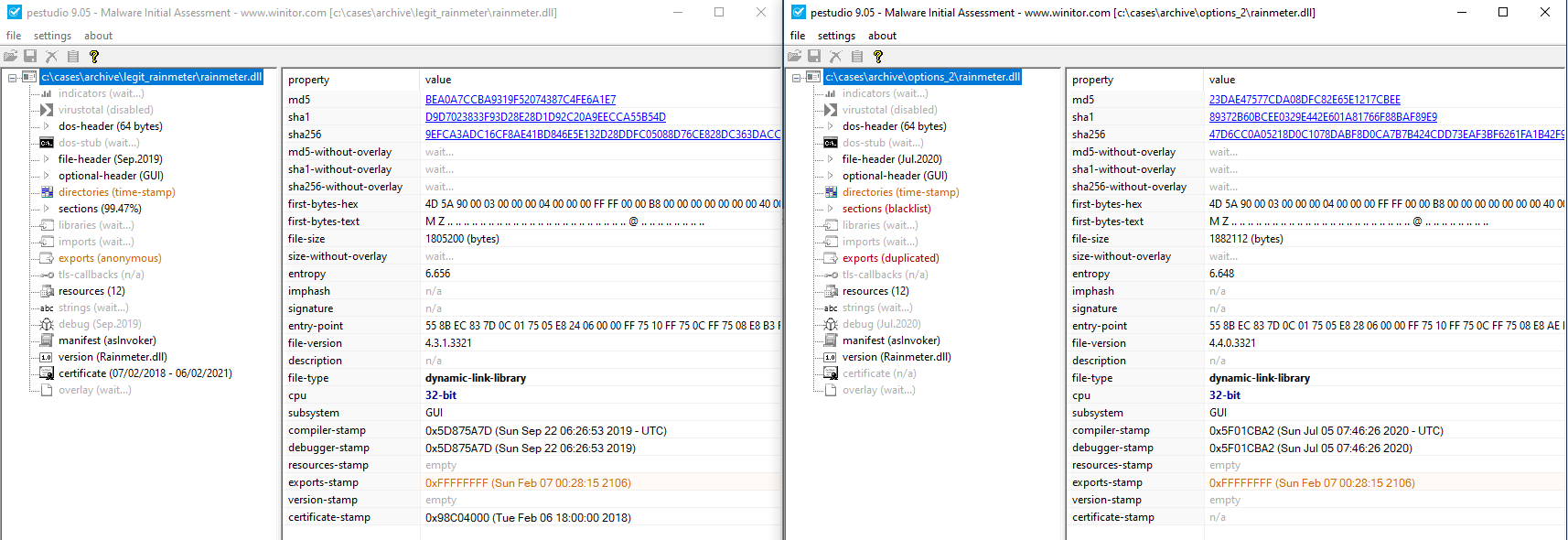

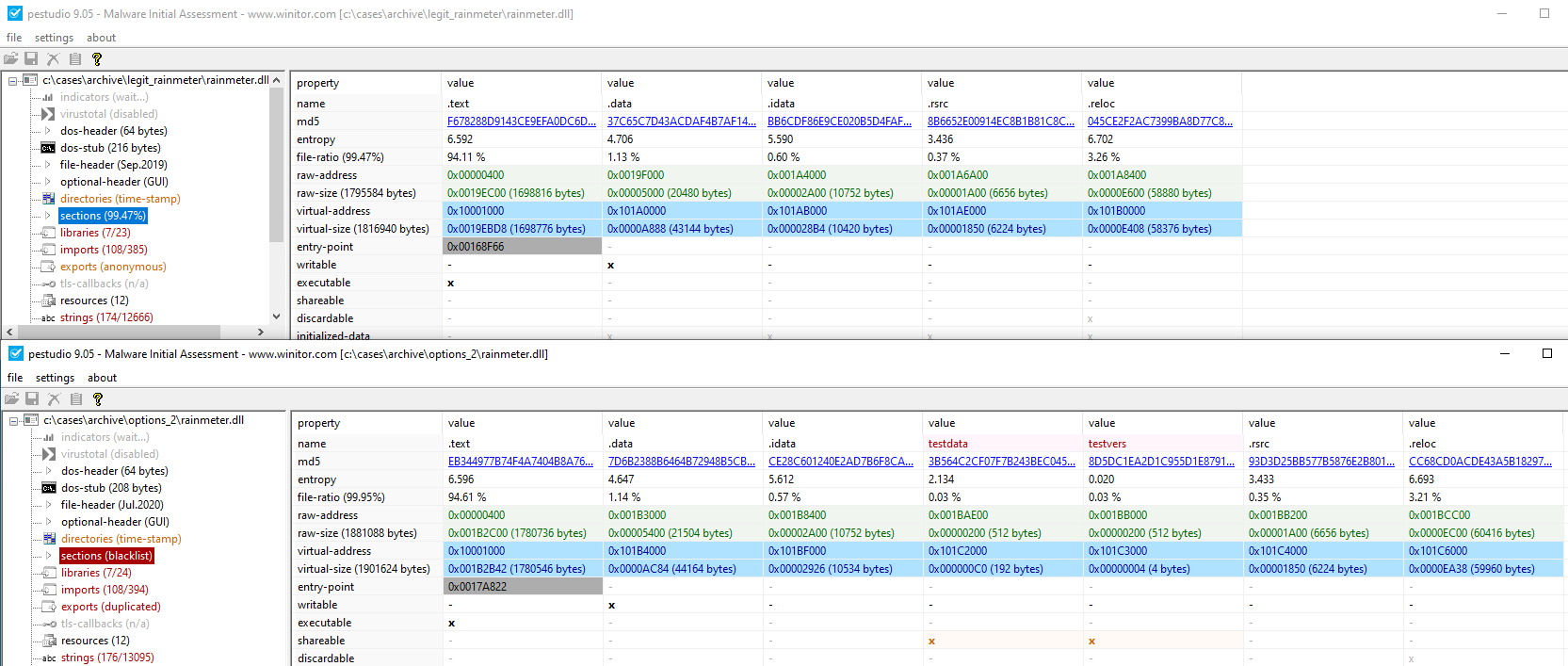

Comparing the rainmeter.dll samples provided more interesting findings. Initially, it was obvious that the two samples were not the same, since the hashes did not line up. The sizes of the files were significantly different from one another and the compile dates were also quite different. Additionally, there was some variability in the imports, exports, strings and other properties. Further, the suspected malicious DLL was not digitally signed and had additional sections not present in the legitimate Rainmeter DLL.

It is important to note that the code base for Rainmeter is publicly available on GitHub under the GNU General Public License v2.0. This would have allowed the threat actor to openly review/modify the existing rainmeter.dll file contents and compile it into the suspected malicious DLL we saw during our investigation.

After completing these comparisons to confirm that the Rainmeter DLL was likely malicious, it was time for a deeper and more focused look at the samples using a debugger for dynamic analysis.

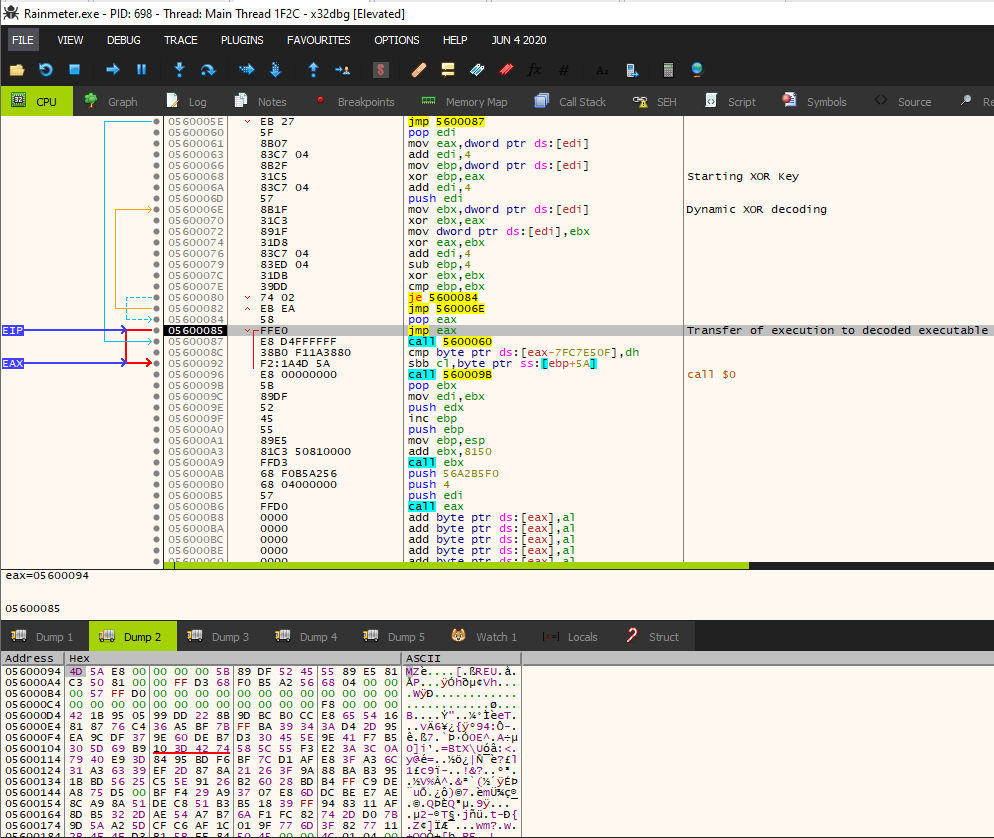

Dynamic Analysis of the Malicious Rainmeter Sample

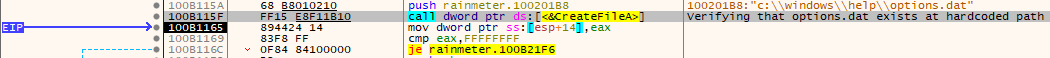

Now that we had identified samples for deeper inspection, we stopped the comparisons to the legitimate Rainmeter application and focused on the analysis of the suspicious samples recovered. We placed the samples of rainmeter.exe and rainmeter.dll recovered from the investigation into our analysis environment and began debugging Rainmeter. Shortly after starting analysis, rainmeter.exe loaded rainmeter.dll as expected, and subsequently called its ordinal 1 exported function. Continuing the execution, there were calls to CreateFileA, where the sample was looking for the hardcoded path C:\Windows\help\options.dat.

After the call to CreateFileA, there is a comparison of the result of the call to CreateFileA to FFFFFFFF to determine if it has a valid handle to the file or not. If there is no valid handle, the program exits.

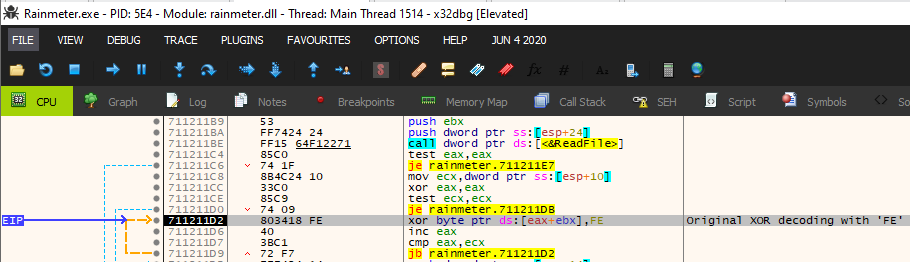

Originally it was not obvious that options.dat was necessary for the analysis of the malicious Rainmeter sample as .dat files are not part of the normal Rainmeter application. However, a version of options.dat was recovered in order to continue analysis. Once the “dat” file was placed in the expected location, the program then allocated space on the heap and read the contents of options.dat into memory. After the contents of options.dat were read into memory, the sample performed a first-level decoding of the contents by XOR-ing the contents with the value FE.

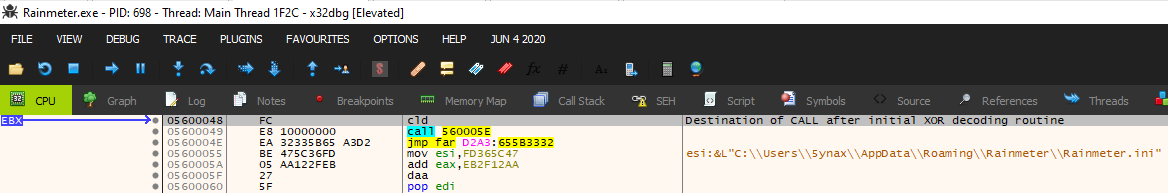

Once the first decoding routine is completed, the malicious Rainmeter application closes the handle to options.dat. When the program closes the handle to options.dat, it is removed from the file system. This is a built-in anti-analysis technique employed to hinder recovery of the .dat file for analysis. At this point, the data read into the program was still a blob of unrecognizable code. However, at the end of the XOR decoding routine, there is a CALL EBX instruction that transfers execution to the recently decoded data. Following EBX in the disassembled view shows that this is valid code. At this stage of analysis, Rainmeter has decoded its options.dat payload, loaded it into memory and executed it. Future analysis confirmed that this was the end of the Vatet loader routine, and execution was passed to the Cobalt Strike shellcode loader.

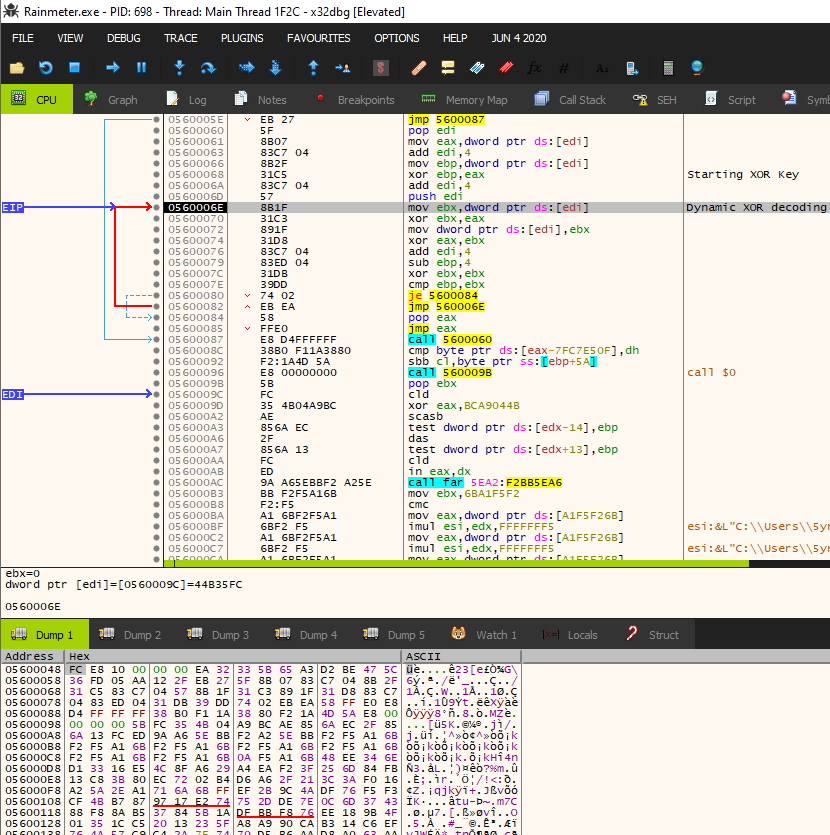

By this point, we realized that the Vatet loading mechanism was completed, but we wanted to validate the identity of the final payload, so we pressed on. Further along in the execution, there is a second decoding routine where an additional dynamic XOR loop is used to decode and rewrite the contents of the executable code. If this routine looks familiar, it’s probably because you are noticing the Cobalt Strike decoding mechanism. This routine begins by obtaining a pointer to the first four bytes of the imported executable code and setting it as the starting XOR key. The code then executes a loop acting on four bytes at a time, XORing the imported code with the starting XOR key. Next, the loop writes the XOR’d value back into the data segment, followed by setting a new XOR key. The new XOR key is determined by XOR’ing the current XOR key with the value decoded by the current key. Once this loop is finished, the sample then uses JMP ECX to transfer execution to the recently decoded executable contents.

At this stage of analysis, we confirmed the content included in options.dat was shellcode that was later decoded via a dynamic XOR routine to create executable code in Rainmeter’s process memory.

Now that we had the executable contents of the XOR’d executable code from options.dat available in memory, we dumped the contents from the memory map section in x64bdg for additional analysis to determine this code’s potential functionality.

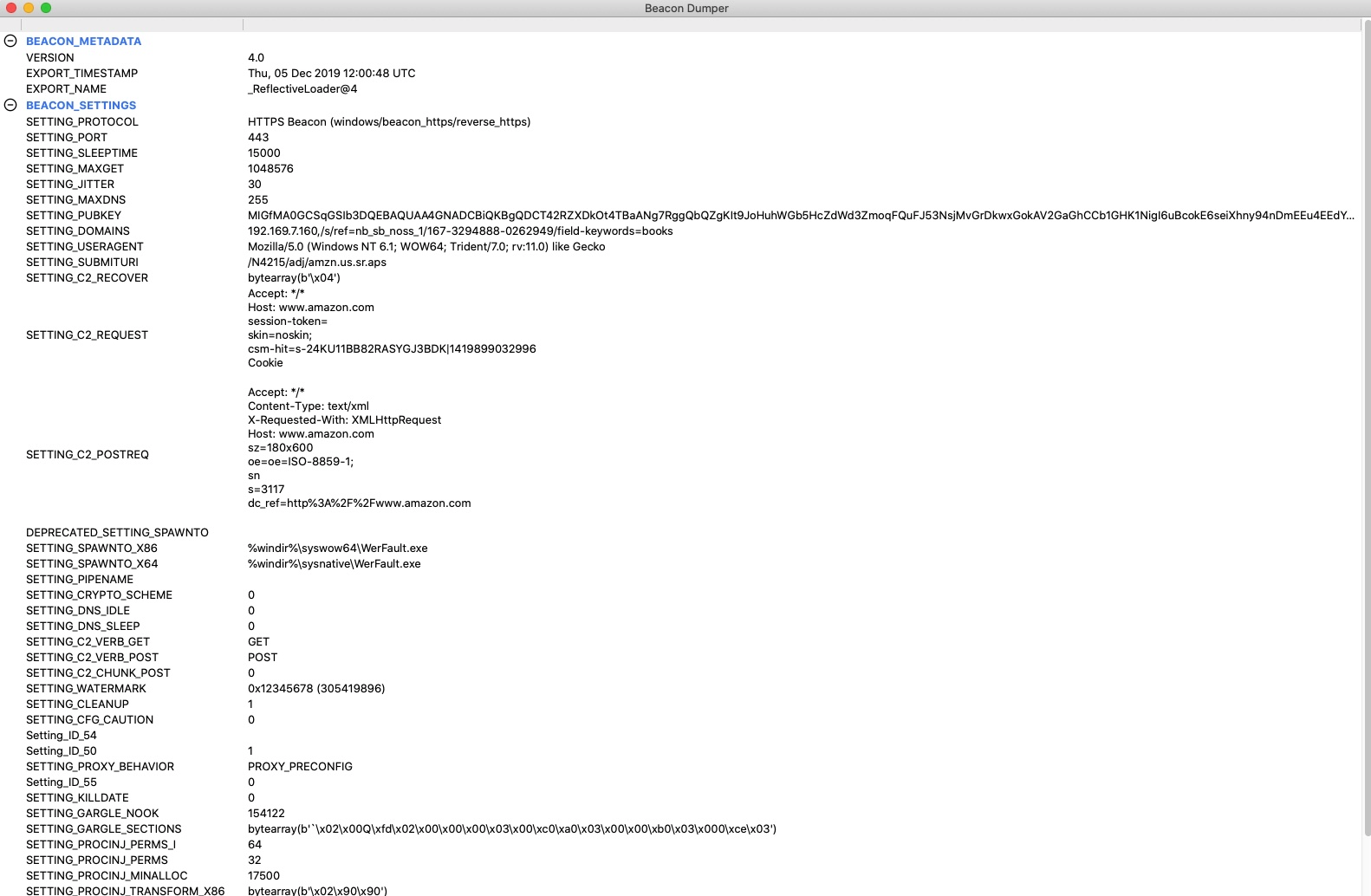

Moving to our dumped sample of the executable code, we conducted an analysis of the strings to determine if there was anything obvious to correlate dynamic analysis findings. In doing this, we identified a reference to beacon.dll, which is most often associated with the DLL version of Cobalt Strike’s beacon. Additionally, loading the isolated PE into PeStudio showed the following references to an exported function _ReflectiveLoader@4, which is a known exported function of Cobalt Strike.

To confirm whether the extracted payload was a Cobalt Strike beacon or not, we utilized a Cobalt Strike beacon parser, which dumped the beacon’s decoded configuration.

The confirmed Cobalt Strike beacon shows a typical implementation of Cobalt Strike’s HTTPS beacon using malleable C2 profiles. Specifically, the Amazon browsing traffic profile created by harmjoy was used in this beacon.

Continue reading: Next Up: "PyXie Lite"

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42