Executive Summary

This tutorial is designed for security professionals who investigate suspicious network activity and review network packet captures (pcaps). Familiarity with Wireshark is necessary to understand this tutorial, which focuses on Wireshark version 3.x.

Dridex is the name for a family of information-stealing malware that has also been described as a banking Trojan. This malware first appeared in 2014 and has been active ever since.

Today’s Wireshark tutorial reviews Dridex activity and provides some helpful tips on identifying this family based on traffic analysis.

Note: Our instructions assume you have customized Wireshark as described in our previous Wireshark tutorial about customizing the column display.

You will need to access a GitHub repository with ZIP archives containing pcaps used for this tutorial.

Warning: Some of the pcaps used for this tutorial contain Windows-based malware. There is a risk of infection if using a Windows computer. We recommend you review this pcap in a non-Windows environment like BSD, Linux or macOS if at all possible.

Dridex Distribution

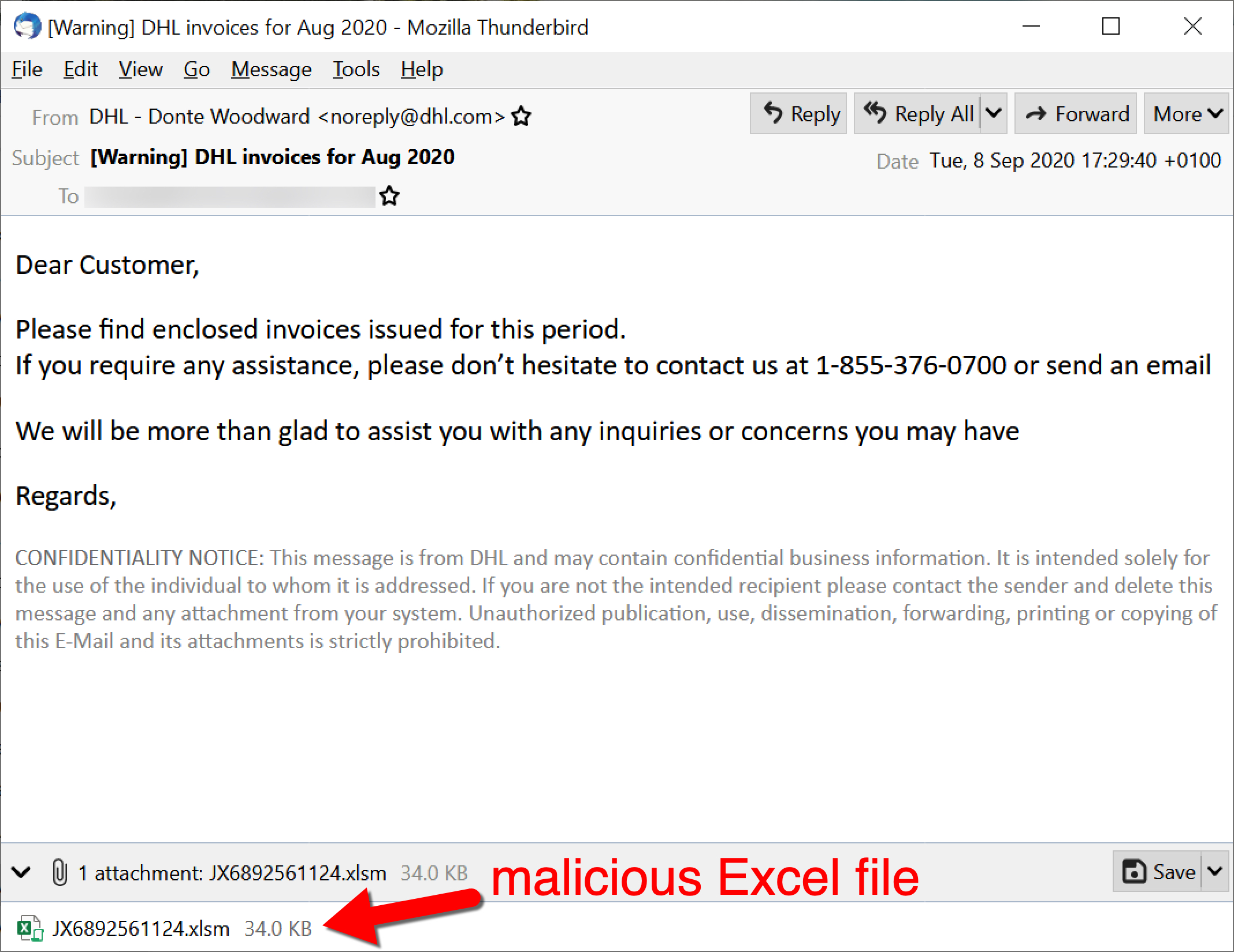

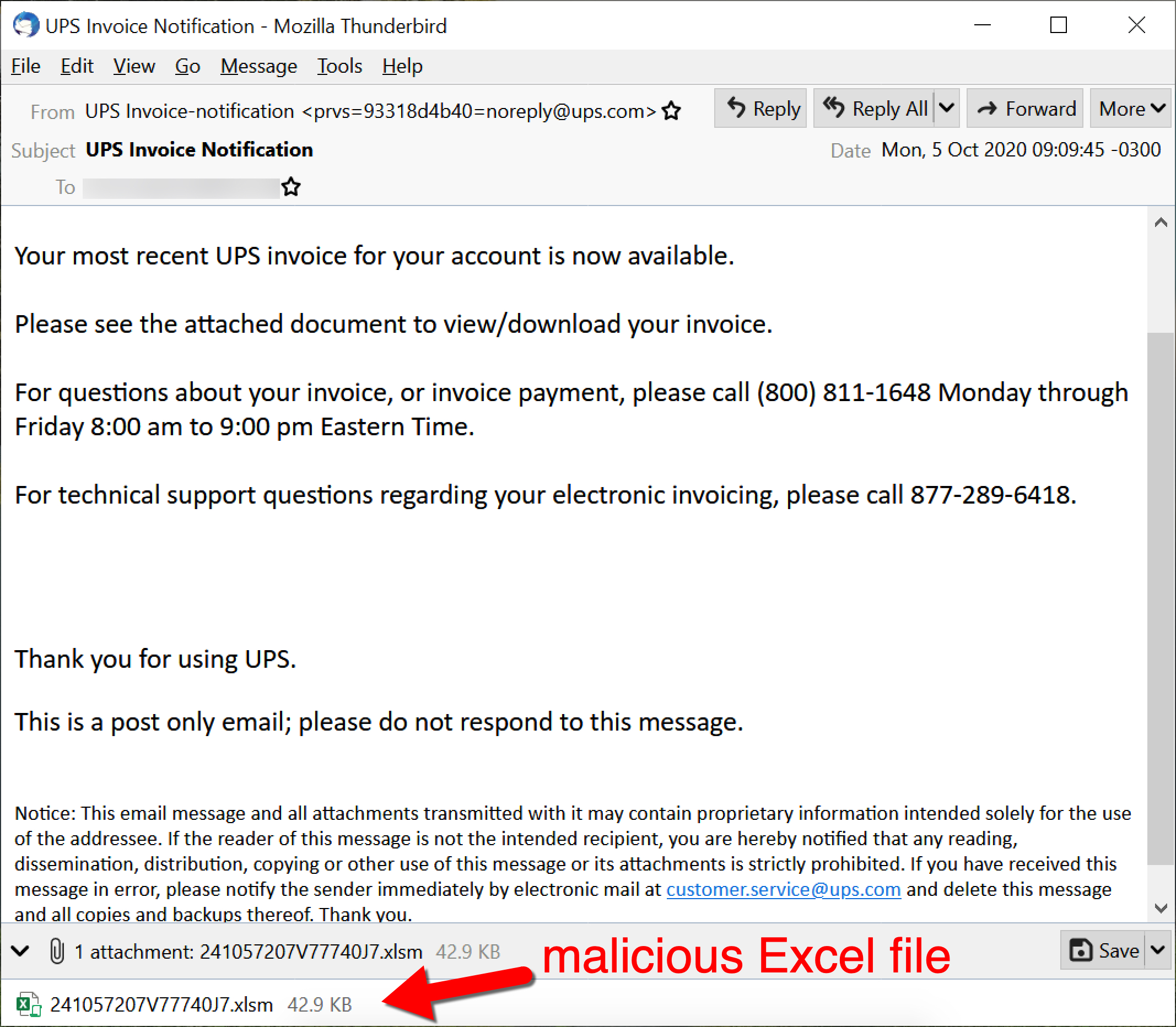

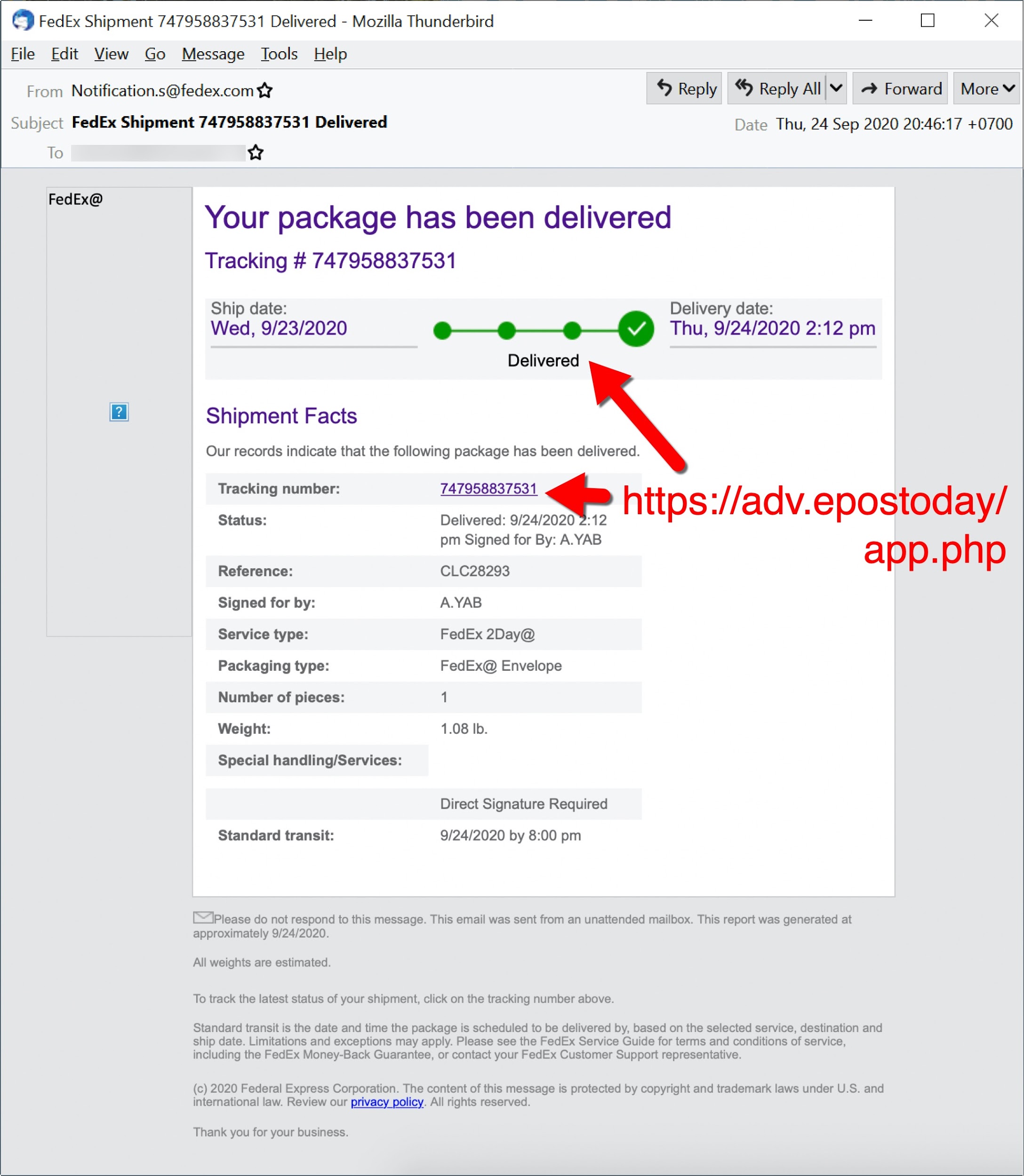

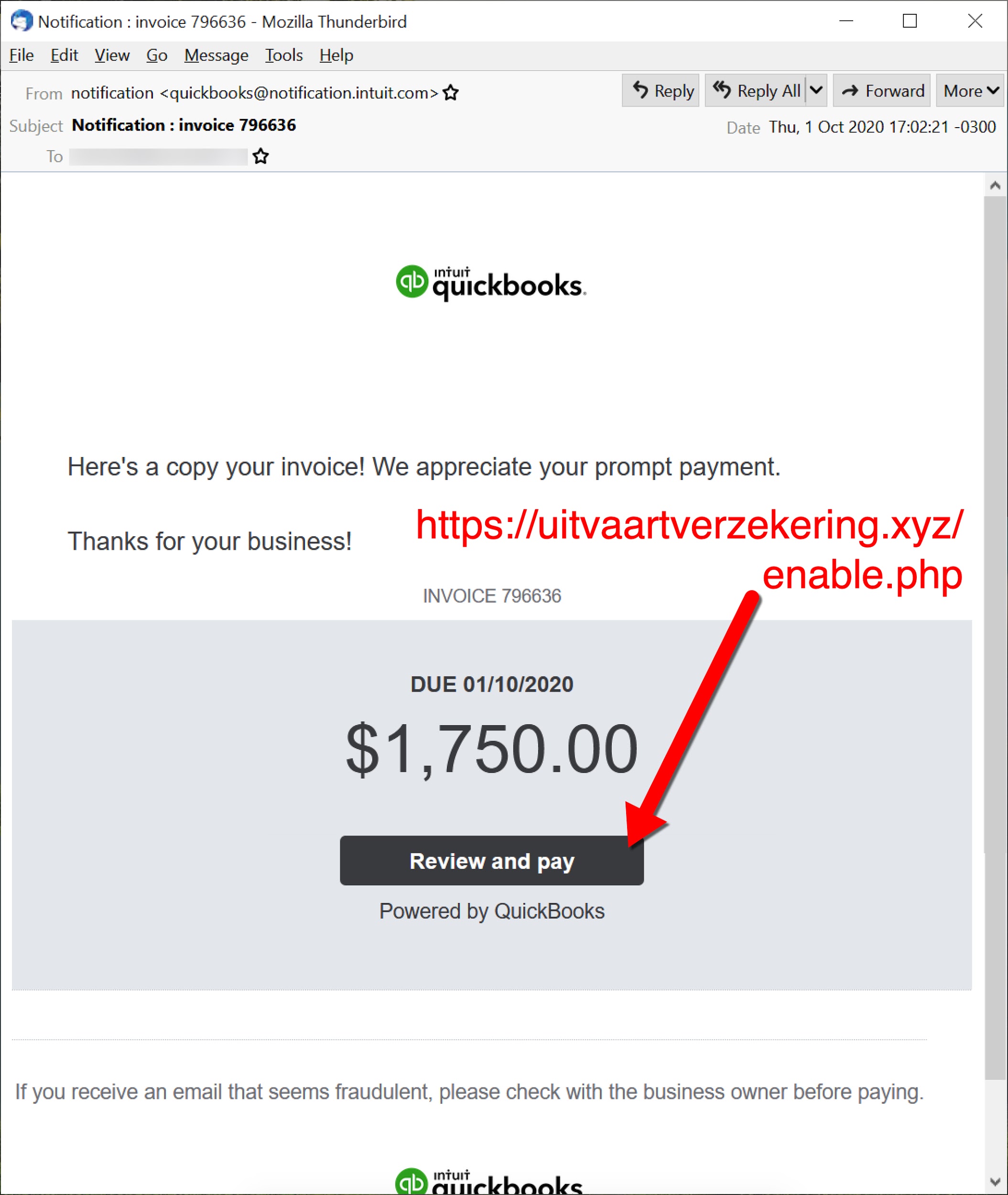

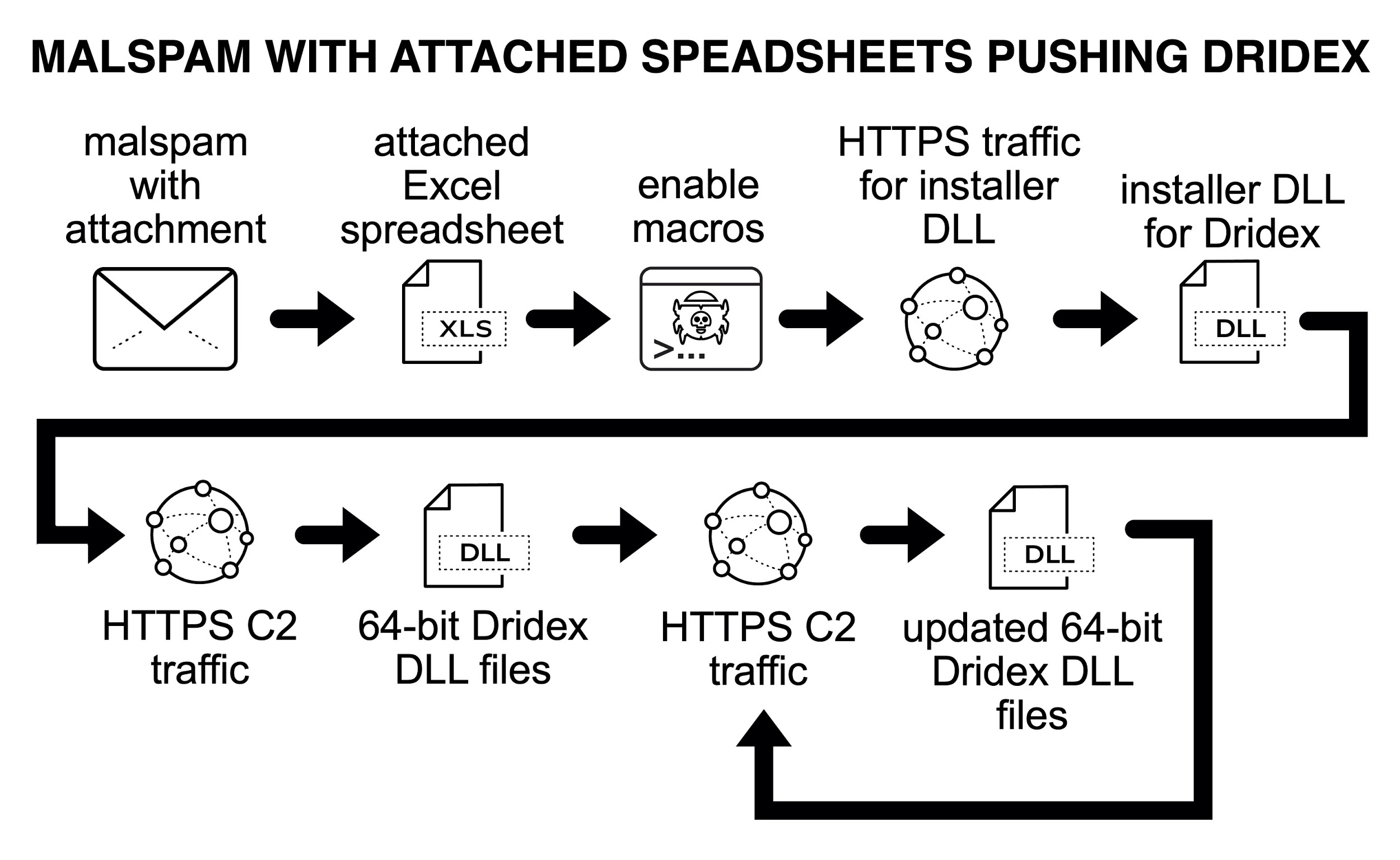

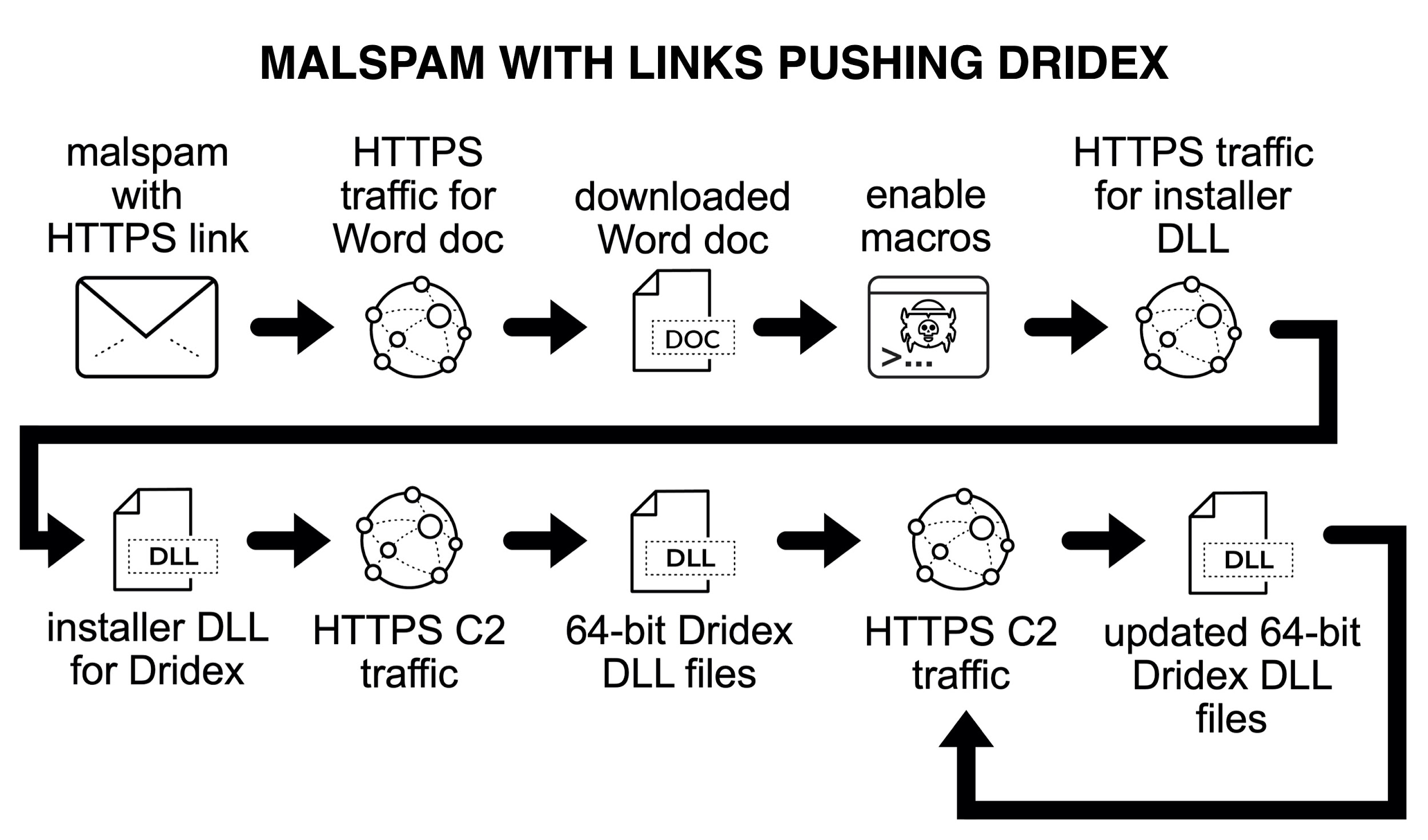

To understand Dridex network traffic, you should understand the chain of events leading to an infection. Dridex is commonly distributed through malicious spam (malspam). Waves of this malspam usually occur at least two or three times a week. Some emails delivering Dridex contain Microsoft Office documents attached, while other emails contain links to download a malicious file. Figures 1 through 4 show some recent examples.

The initial malicious file can be a Microsoft Office document with a malicious macro, or it could be a Windows executable (EXE) disguised as some sort of document. Either way, potential victims need to click their way to an infection from this initial file. The initial file retrieves a Dridex installer, although sometimes the initial file is itself a Dridex installer. The Dridex installer retrieves 64-bit Dridex DLL files over encrypted command and control (C2) network traffic. Figures 5 and 6 show what we commonly see for infection chains of recent Dridex activity.

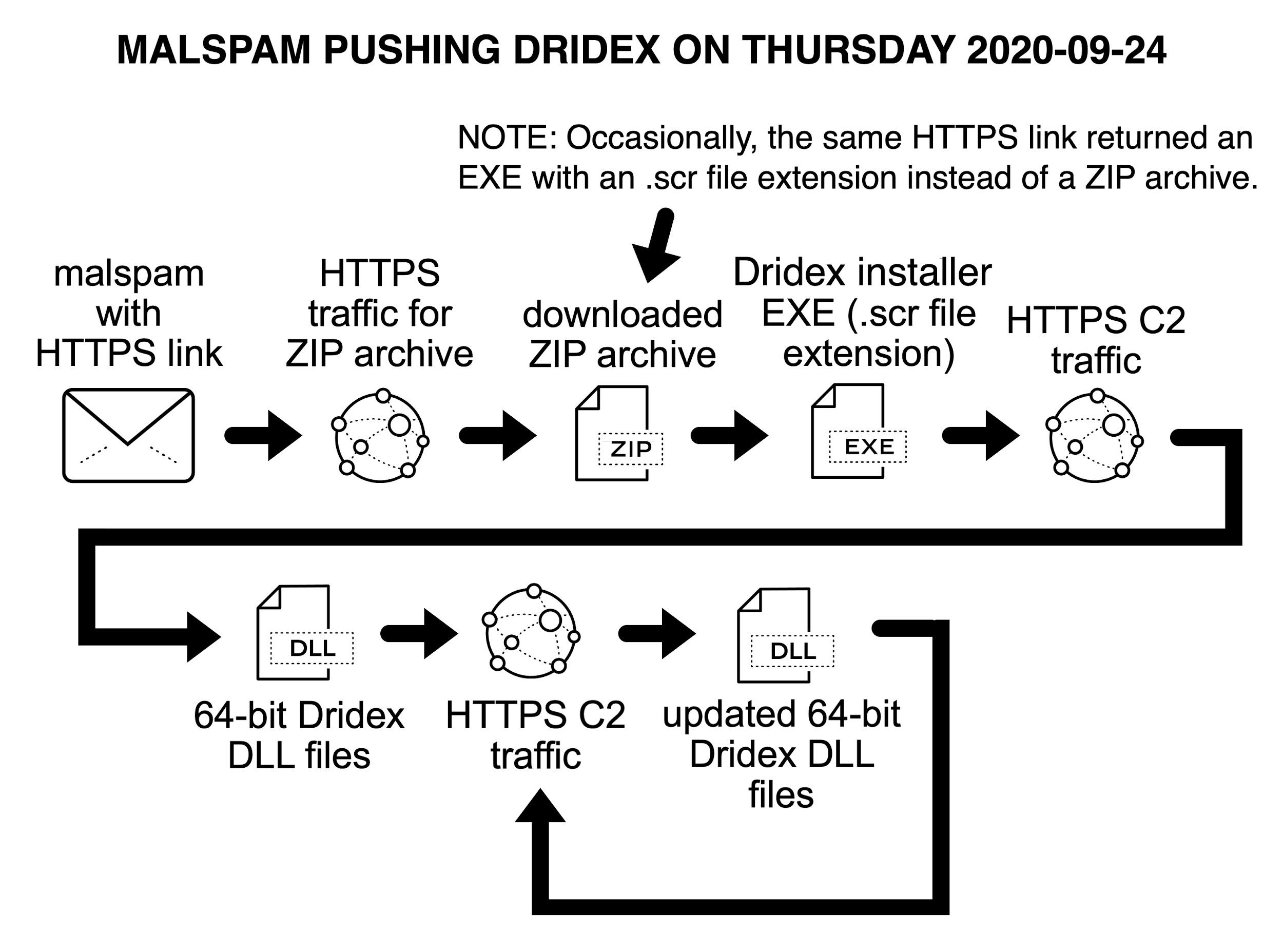

Figure 7 shows another type of Dridex infection chain from malspam, which is not as common as the Office documents used in Figures 5 and 6. On Sept. 24, 2020, links from malspam pushing Dridex didn’t return an Office document. Instead, they returned a Windows executable file. See Figure 7 for details.

As noted in Figures 5 through 7, distribution traffic is most often HTTPS, which makes the initial file or Dridex installer hard to detect because it is encrypted. Fortunately, post-infection traffic caused by Dridex C2 activity is distinctive enough to identify.

Certificates and HTTPS Traffic

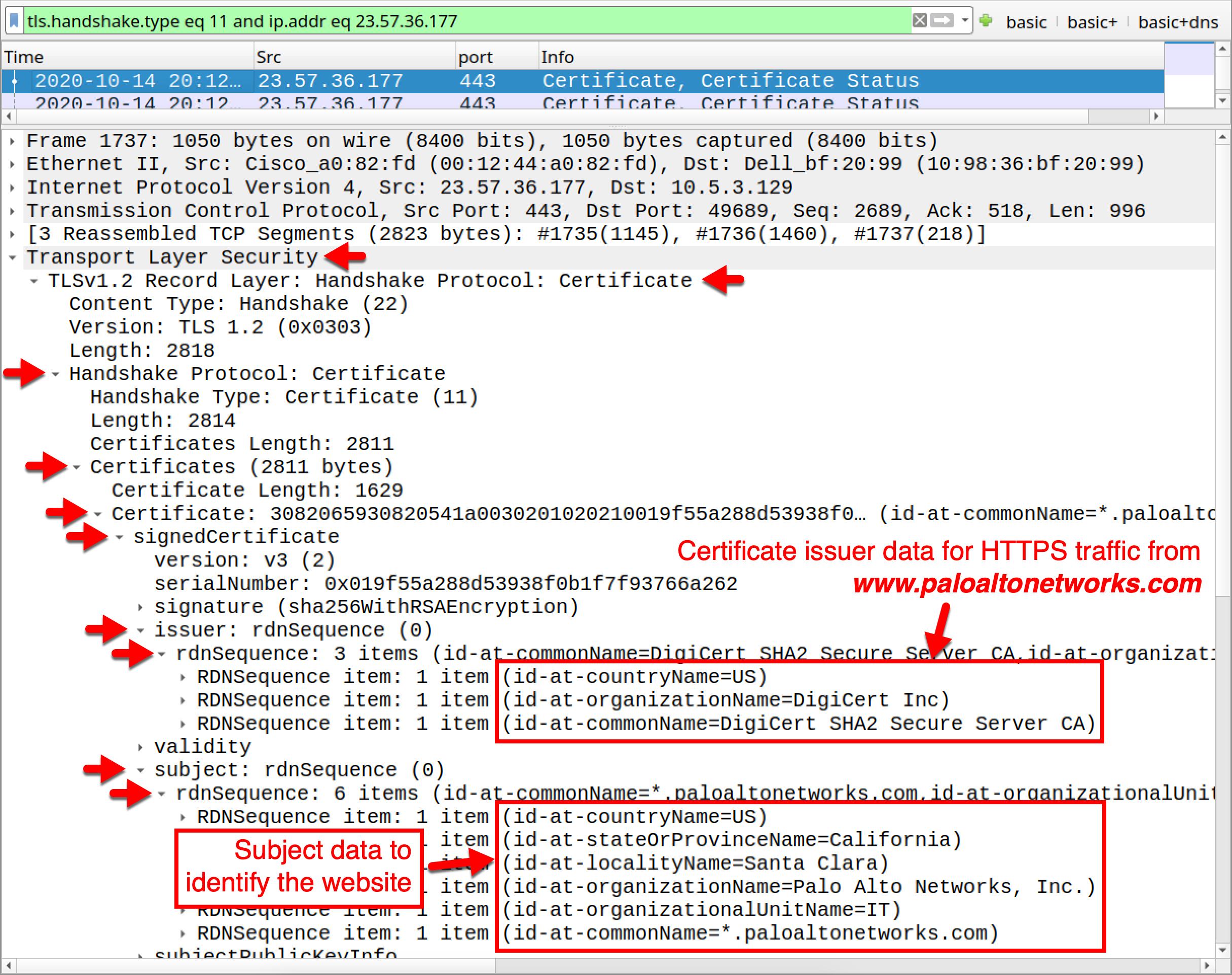

To understand Dridex infection activity, we should also understand digital certificates used for HTTPS traffic.

A digital certificate is used for SSL/TLS encryption of HTTPS traffic. When viewing a website using HTTPS, a certificate is sent by the web server to a client's web browser. Data from this digital certificate is used to establish an HTTPS connection. Certificates contain a website's public key and confirm the website's identity.

Different certificate authorities (CAs) can issue digital certificates for various websites. Certificates are sold to businesses for commercial websites, while some certificate authorities like Let’s Encrypt offer certificates for free.

Certificate information can be viewed from HTTPS traffic in Wireshark. We’ll focus on the following two sections:

- Issuer data about the CA.

- Subject data about the website.

Issuer data reveals the CA that issued the digital certificate. Subject data verifies the identity of the website. Figure 8 shows how to find certificate issuer and subject data for HTTPS traffic from www.paloaltonetworks.com.

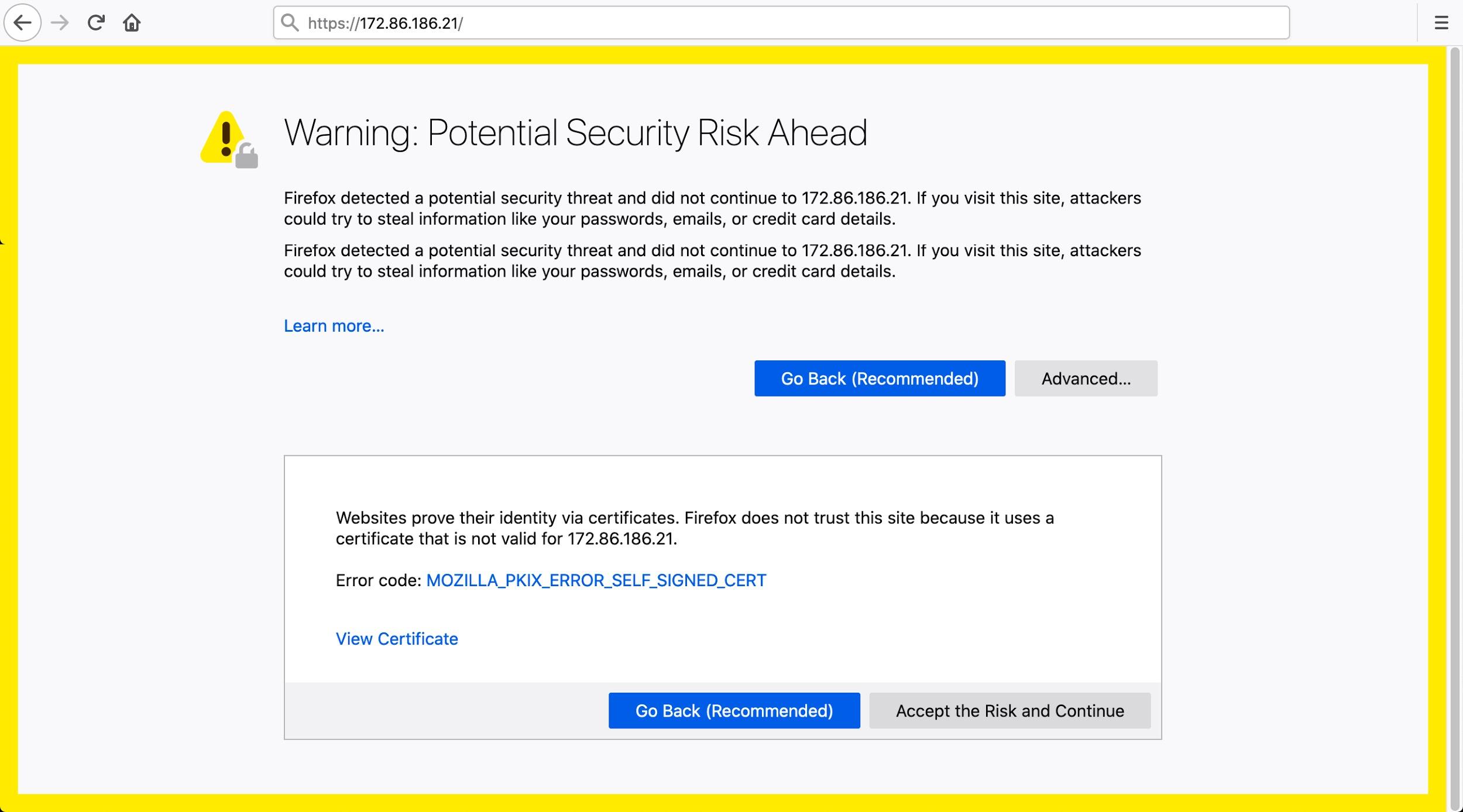

However, when setting up a web server, administrators can generate self-signed certificates. Self-signed certificates are locally generated and not issued by any certificate authority. HTTPS traffic from such servers often generates error messages when viewed in modern browsers, such as Firefox, as shown in Figure 9.

Malware developers often use self-signed certificates for their C2 servers. Why? Because self-signed certificates are quick, easy and free to create. Furthermore, HTTPS C2 traffic for malware does not involve a web browser, so the encrypted traffic works without any errors or warnings.

Generating self-signed certificate involves entering values for the following fields (some of these are often left blank):

- Country name (2 letter code).

- State or province name.

- Locality name (usually a city name).

- Organization name.

- Organizational unit name.

- Common name (for example, fully qualified host name).

- Email address.

These fields are used for subject data that identifies the website, but the same fields and values are also used for the issuer, since the certificate was generated locally on the web server itself.

Malware authors often use random, default or fake values in these fields for self-signed certificates. For example, Trickbot’s HTTPS C2 traffic often uses example.com for the Common Name field. HTTPS C2 traffic from recent IcedID malware infections has used the following values in its certificate issuer fields:

- Country name: AU

- State or province name: Some-State

- Organization name: Internet Widgits Pty Ltd

- Common name: localhost

Patterns in certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic are somewhat unique when compared to other malware families. They can be key to identifying Dridex infections.

Pcaps of Dridex Infection Activity

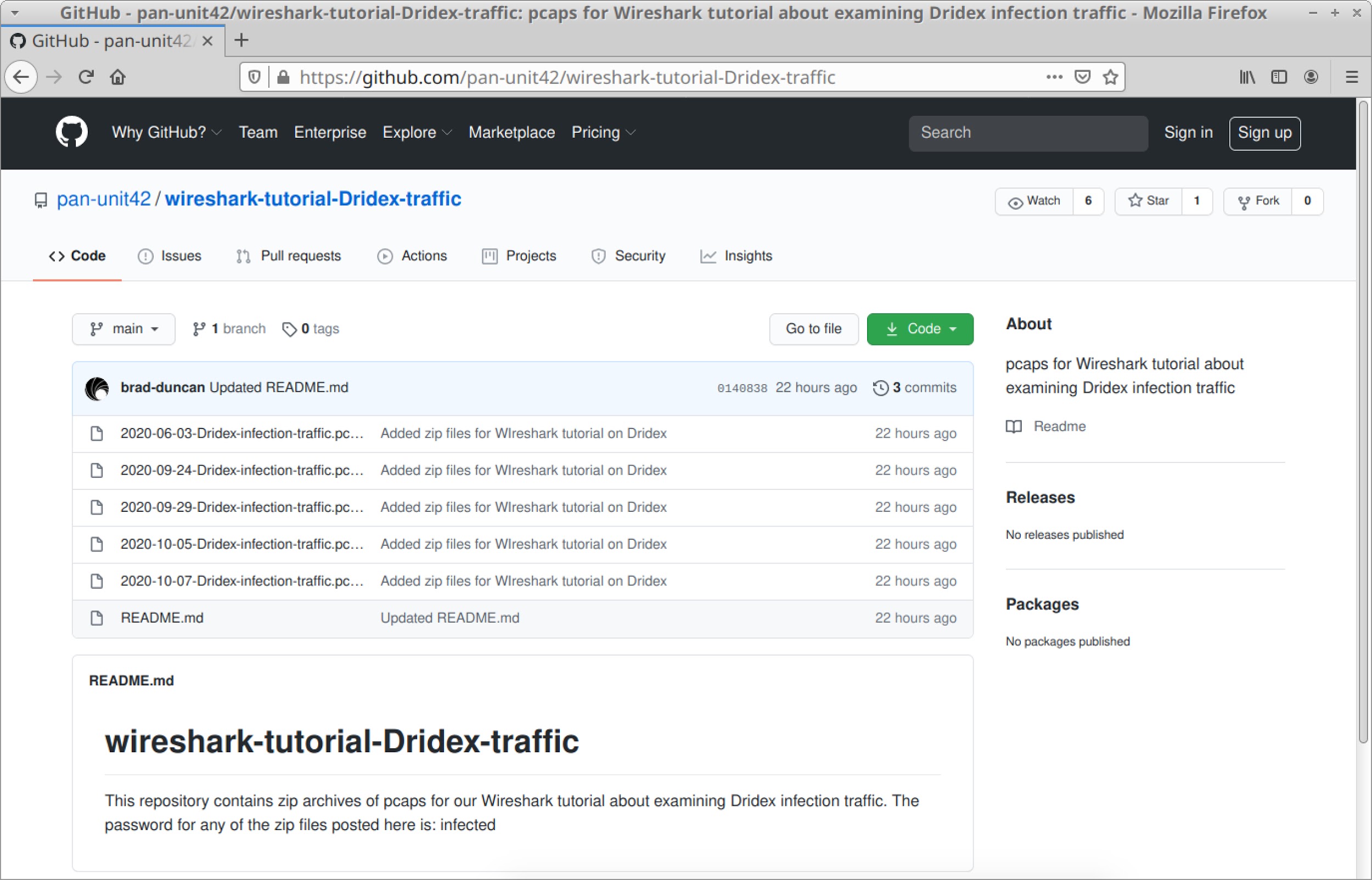

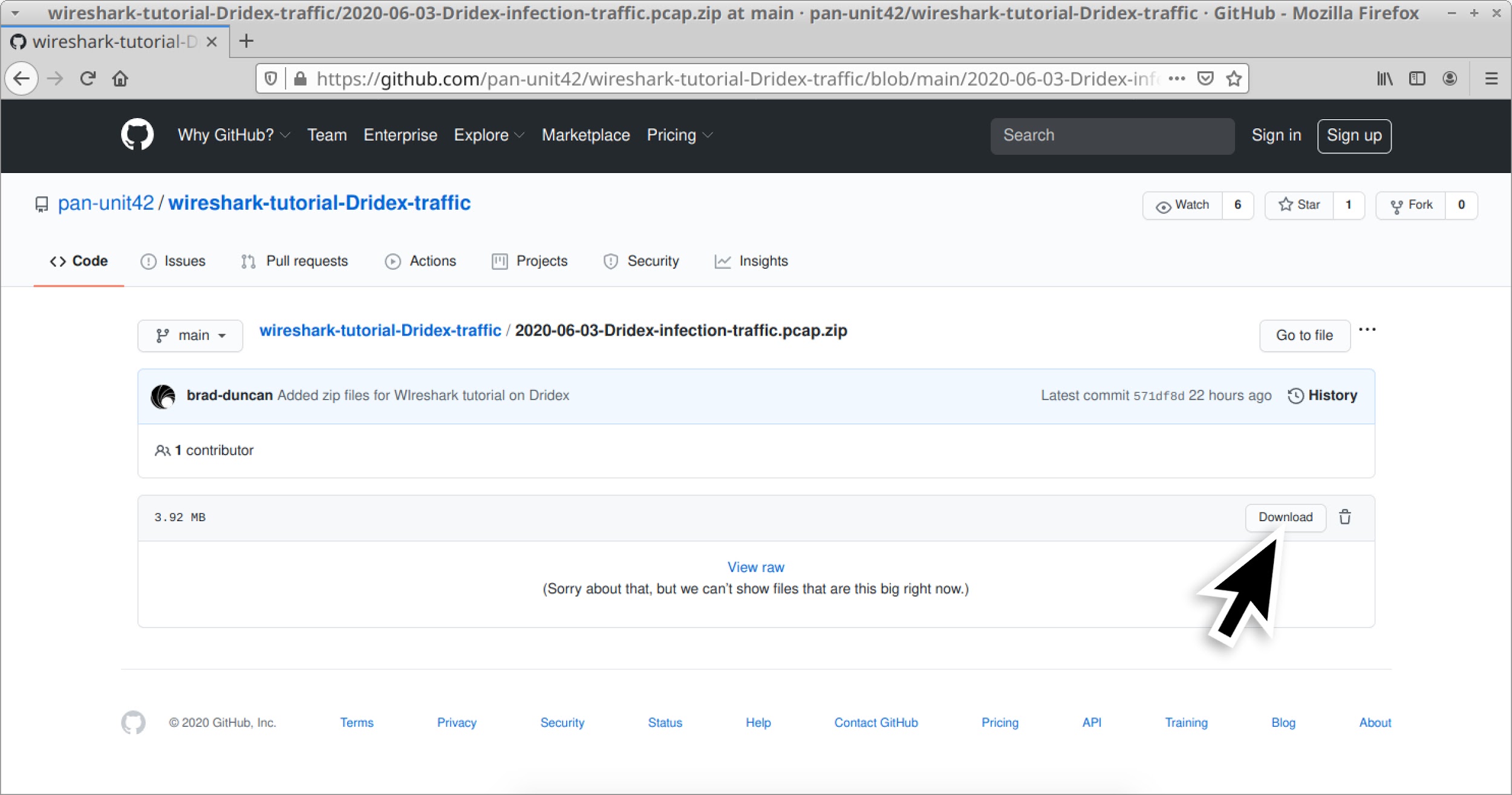

Five password-protected ZIP archives containing pcaps of recent Dridex network traffic are available at this GitHub repository. Once on the GitHub page, click on each of the ZIP archive entries, and download them as shown in Figures 10 and 11.

Use infected as the password to extract pcaps from these ZIP archives. This will result in five pcap files:

- 2020-06-03-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

- 2020-09-24-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

- 2020-09-29-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

- 2020-10-05-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

- 2020-10-07-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

Example One: 2020-06-03-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

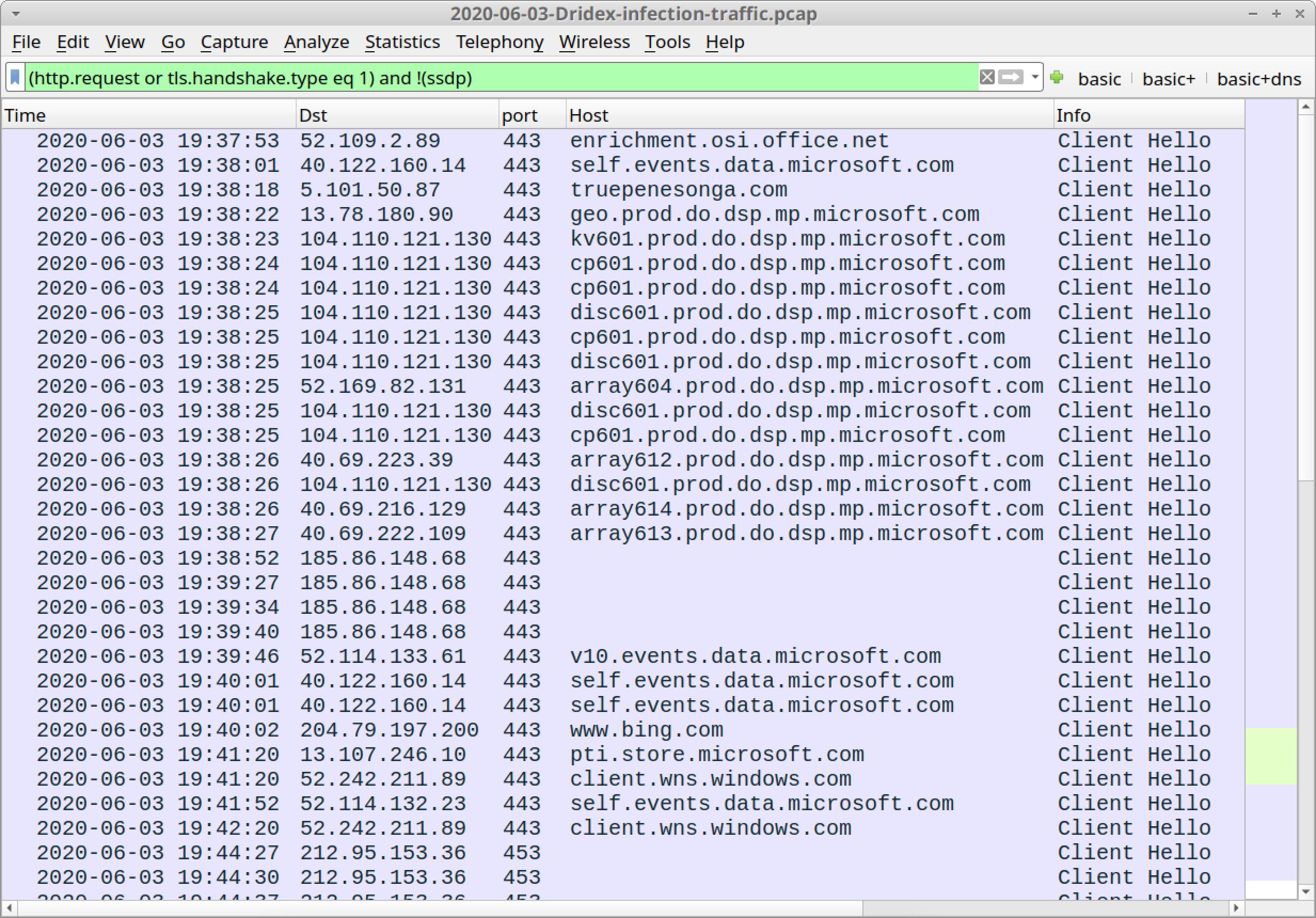

Open 2020-06-03-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap in Wireshark, and use a basic web filter as described in this previous tutorial about Wireshark filters. Our basic filter for Wireshark 3.x is:

(http.request or tls.handshake.type eq 1) and !(ssdp)

Dridex infection traffic consists of two parts:

- Initial infection activity.

- Post-infection C2 traffic.

Initial infection activity occurs when a victim downloads a malicious file from an email link. Initial infection activity also includes the malicious file loading an installer for Dridex. In some cases, you may not have an initial download because the malicious file is an attachment from an email. In other cases, you might not see a Dridex installer loaded because the initial file itself is an installer. In many cases, this activity happens over HTTPS, so we will not see any URLs, just a domain name.

Post-infection activity is HTTPS C2 traffic that occurs after the victim is infected. This will always occur during a successful Dridex infection. This C2 traffic communicates directly with an IP address, so there are no domain names associated with it. It also has unusual certificate issuer data as detailed below.

Figure 12 shows the first example opened in Wireshark using our basic web filter. The lines without a domain name are Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic.

The first pcap shown in Figure 12 shows the following traffic directly to IP addresses instead of domain names. This is most likely Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic:

- 185.86.148[.]68 over TCP port 443

- 212.95.153[.]36 over TCP port 453

Other domains seen using our basic web filter are system traffic using domains that end with well-known names like microsoft.com, office.net or windows.com. The only exception is HTTPS traffic to truepenesonga[.]com, which is near the beginning of the pcap at 19:38:18 UTC. This is likely the Dridex installer. A quick Google search indicates truepenesonga[.]com is associated with malware.

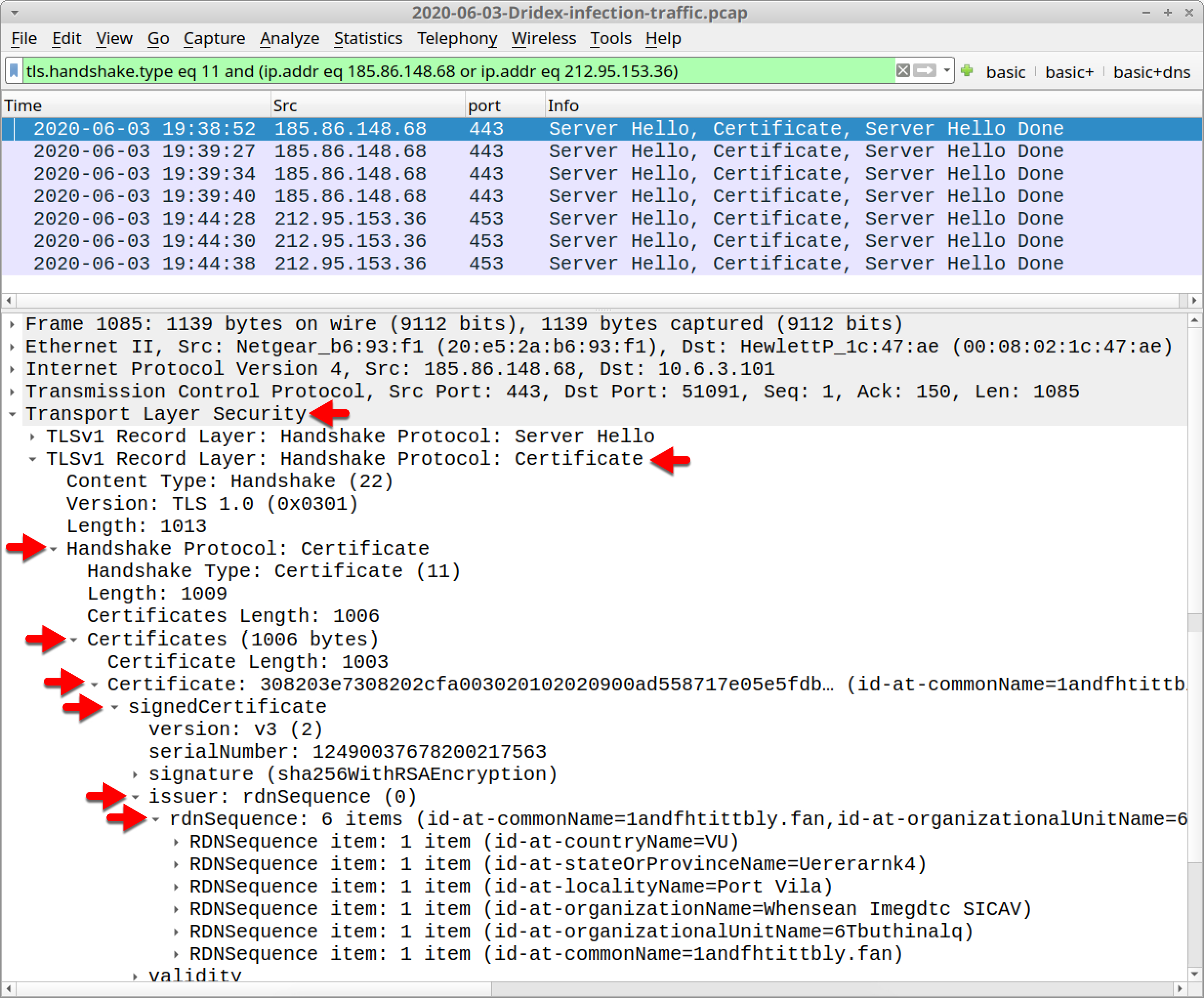

Focus on the post-infection Dridex C2 traffic. Use the following filter in Wireshark to look at the certificate issuer data for HTTPS traffic over these two IP addresses:

tls.handshake.type eq 11 and (ip.addr eq 185.86.148.68 or ip.addr eq 212.95.153.36)

After the filter has been applied, select the first frame in your Wireshark column display, then go to the frame details panel and expand the values as shown in Figure 13 until you work your way to a list of lines that start with the term RDNSequence item.

Note the RDNSequence items for HTTPS traffic to 185.86.148[.]68 and their values:

- id-at-countryName=Vu

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Uererarnk4

- id-at-localityName=Port Vila

- id-at-organizationName=Whensean Imegdtc SICAV

- id-at-organizationUnitName=6Tbuthinalq

- id-at-commonName=1andfhtittbly.fan

Dridex certificate issuer fields frequently has random strings with a number or two sometimes thrown in. However, values for the country name and city or locality often match. In the above example, Vu is the 2-letter country code for Vanuatu, and Port Vila is the capital city of Vanuatu.

Do the same thing for HTTPS traffic to 212.95.153[.]36 and you should find:

- id-at-countryName=AO

- id-at-localityName=Luanda

- id-at-organizationName=Msorest KGaA

- id-at-organizationUnitName=aghat@yongd

- id-at-commonName=arashrinwearc.Ourontizes.ly

We find the locality Luanda is the capital of Angola, which is country code AO. But the other fields appear to have random values. This type of certificate issuer data is a strong indicator of Dridex C2 traffic.

Example Two: 2020-09-24-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

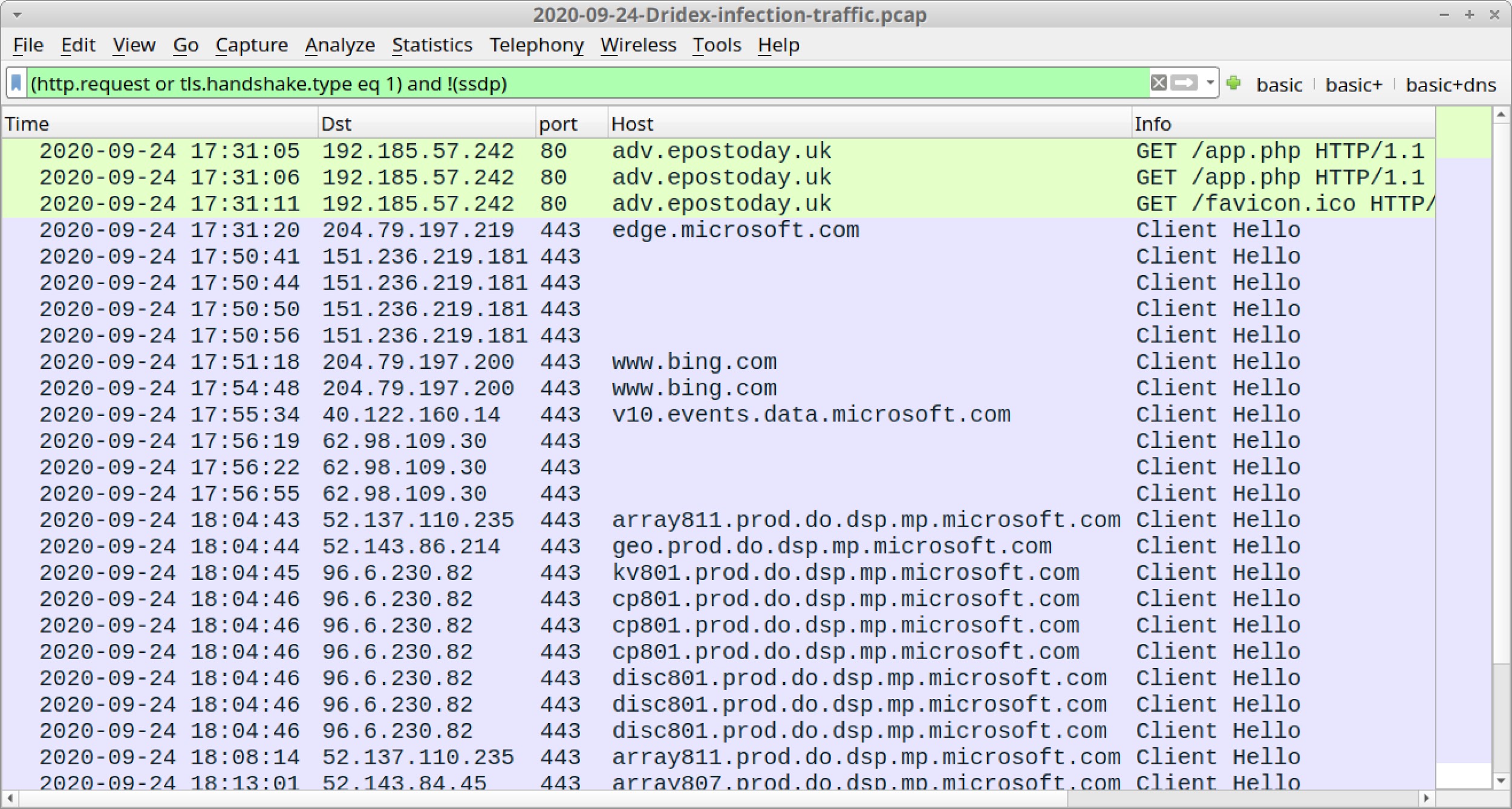

Open 2020-09-24-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 14.

Note how the first three lines are unencrypted HTTP GET requests. This is a link from an email shown earlier in Figure 3. It returned a ZIP archive for the infection chain shown in Figure 7.

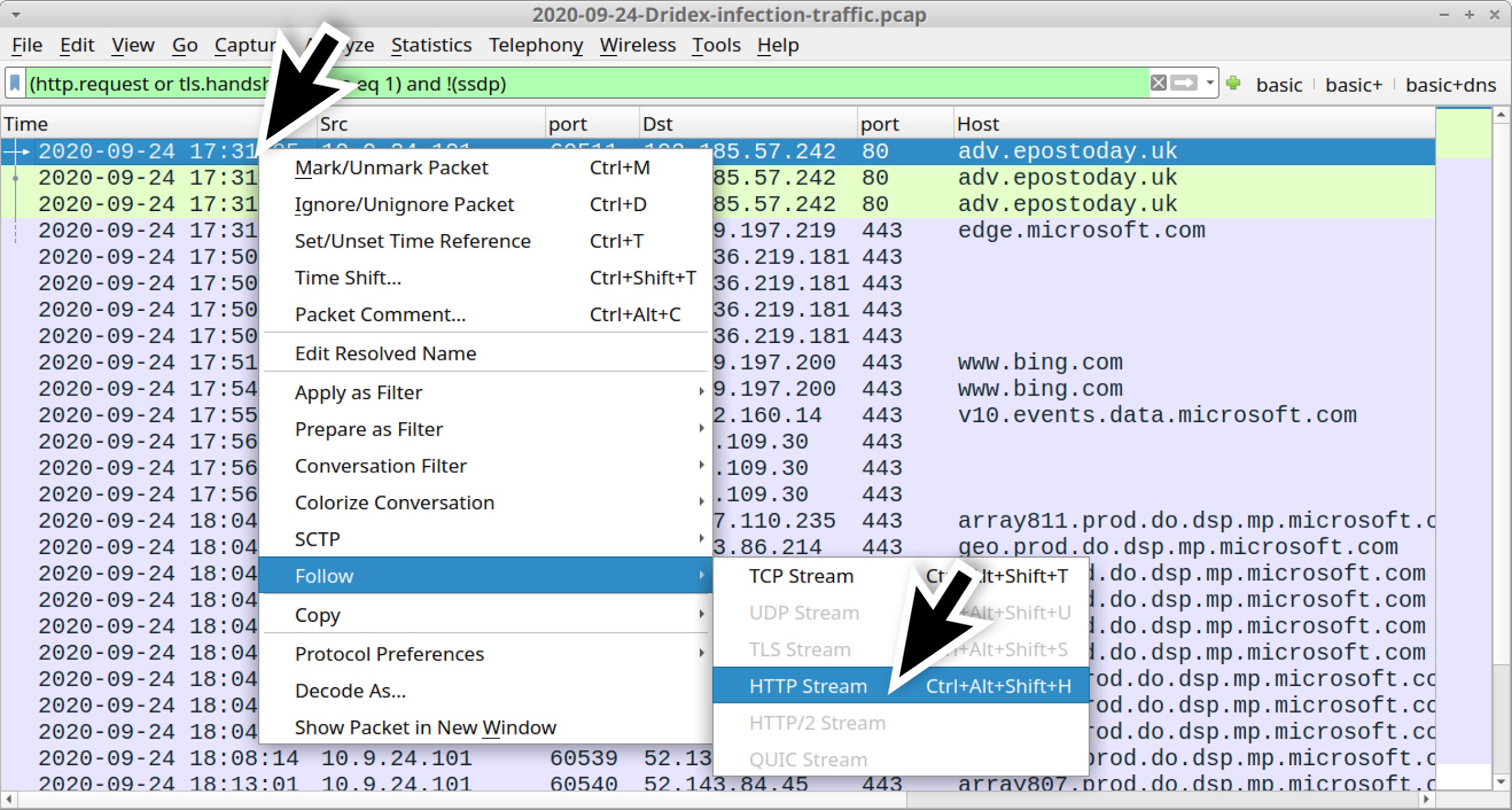

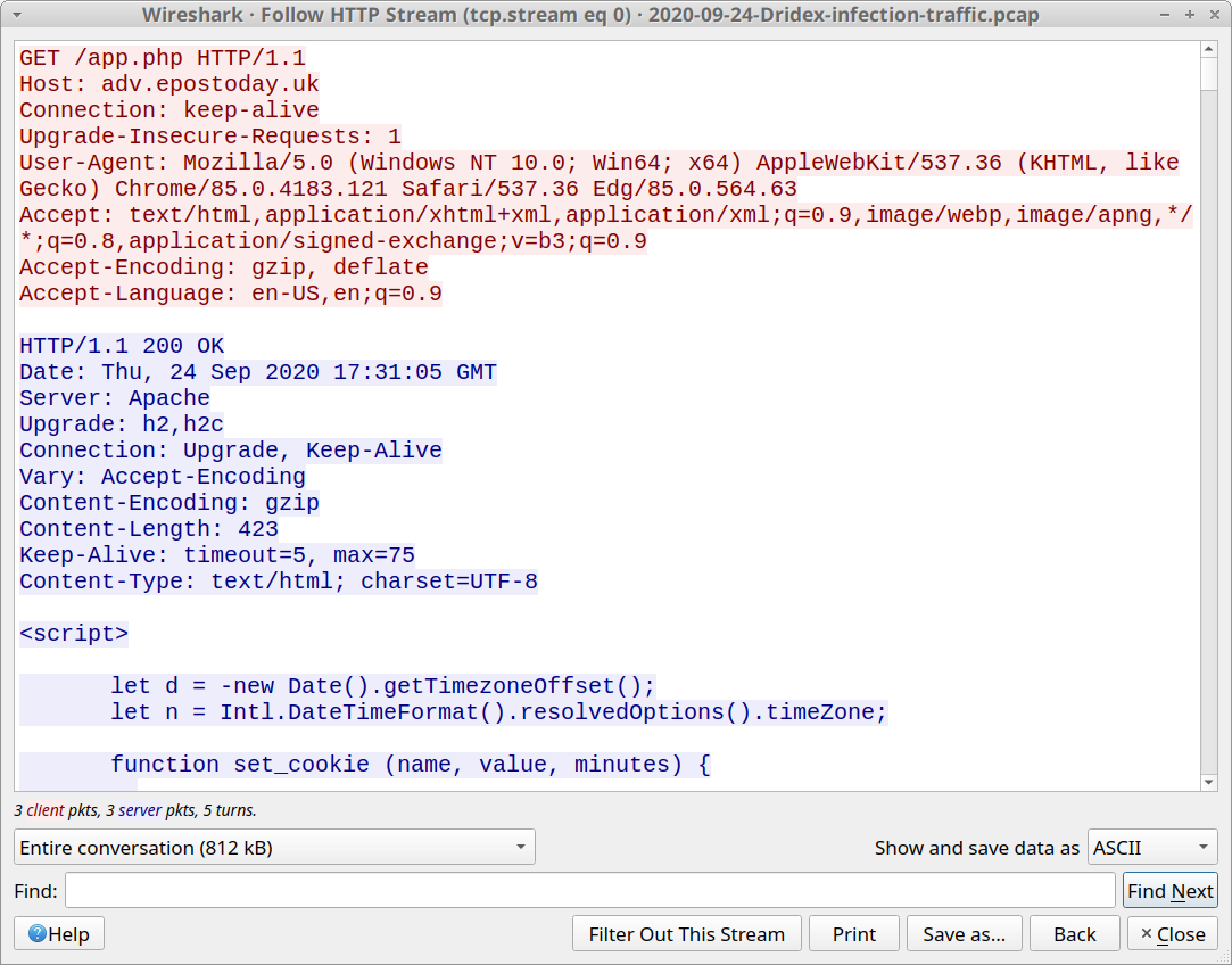

The HTTP stream (not the TCP stream) can be followed. Scroll down to see some script returned, as shown in Figures 15 and 16.

All three HTTP GET requests to adv.epostoday[.]uk are in the same TCP stream. Scroll down near the end before the last HTTP GET request for favicon.ico. You will find the end of a long string of ASCII characters that is converted to a blob and sent to the victim as Ref_Sep24-2020.zip, as shown in Figure 17.

These scripts can be exported by using the ”export HTTP objects” function, as shown in Figure 18.

Once again, focus on the post-infection Dridex C2 traffic. Use the following filter in Wireshark to look at the certificate issuer data for HTTPS traffic over the two IP addresses without domain names in the HTTPS traffic:

tls.handshake.type eq 11 and (ip.addr eq 151.236.219.181 or ip.addr eq 62.98.109.30)

After applying the filter, select the first frame and go to the frame details section. Look for a list of lines that start with the term RDNSequence item as done in our first pcap. Figure 19 shows how to get there in our second pcap for 151.236.219[.]181.

The certificate issuer data is similar to that of the first example. Check the certificate issuer data for both IP addresses and find the data listed below.

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 151.236.219[.]181:

- id-at-countryName=IL

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Anourd Thiolaved Thersile5 Fteda8

- id-at-LocalityName=Tel Aviv

- id-at-organizationName=Wemadd Hixchac GmBH

- id-at-organizationUnitName=moasn@emanc

- id-at-commonName=heardbellith.Icanwepeh.nagoya

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 62.98.109[.]30:

- id-at-countryName=SS

- id-at-LocalityName=Khartoum

- id-at-organizationName=Hedanpr S.p.a.

- id-at-commonName=psprponounst.aquarelle

The locality matches the country name in both cases, but the other fields appear to be random strings. This matches the same pattern as Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic from our first pcap.

Example Three: 2020-09-29-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

Open 2020-09-29-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 20.

Checking through the domains, there are three non-Microsoft domains using HTTPS traffic that might be tied to the initial infection activity:

- dsimportaciones[.]com

- murfreesboro.fairwayconcierge[.]com

- ryner.net[.]au

Since those are URL-specific and the contents are not shown, focus on the post-infection Dridex C2 traffic. Use the following filter in Wireshark to look at the certificate issuer data for HTTPS traffic over the two IP addresses without domain names in the HTTPS traffic:

tls.handshake.type eq 11 and (ip.addr eq 67.79.105.174 or ip.addr eq 144.202.31.138)

After applying the filter, select the first frame, go to the frame details section and look for a list of lines that start with the term RDNSequence item as done in our first two examples. Figure 21 shows how to get there in our third pcap for 67.79.105[.]174.

The certificate issuer data follows the same pattern as our first two examples. Check the issuer data for both IP addresses to find the data listed below.

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 67.79.105[.]174:

- id-at-countryName=MN

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Listth Thearere8 berponedt tithsalet

- id-at-LocalityName=Ulaanbaatar

- id-at-organizationName=Massol SE

- id-at-commonName=Atid7brere.Speso_misetr.stada

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 144.202.31[.]138:

- id-at-countryName=SS

- id-at-LocalityName=Khartoum

- id-at-organizationName=Hedanpr S.p.a.

- id-at-commonName=psprponounst.aquarelle

Of note, certificate issuer data for 144.202.31[.]138 in the third example from 2020-09-29 is the same as for 62.98.109[.]30 in the second example from 2020-09-24.

Example Four: 2020-10-05-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

Open 2020-10-05-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 22.

Checking through the domains, there is one non-Microsoft domain using HTTPS traffic that might be tied to the initial infection activity:

- vardhmanproducts[.]com

Once again, the focus will be on post-infection Dridex C2 traffic. Use the following filter in Wireshark to look at the certificate issuer data for HTTPS traffic over the two IP addresses without domain names in the HTTPS traffic:

tls.handshake.type eq 11 and (ip.addr eq 85.114.134.25 or ip.addr eq 85.211.162.44)

After applying the filter, select the first frame, go to the frame details section and work your way to a list of lines that start with the term RDNSequence item as done in the first three examples.

The certificate issuer data follows the same pattern as the first three examples. Check the issuer data for both IP addresses, and you should find the data listed below.

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 85.114.134[.]25:

- id-at-countryName=NZ

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Cepli thade0 ithentha temsorer

- id-at-LocalityName=Wellington

- id-at-organizationName=Lling Lovisq NL

- id-at-organizationalUnitName=Punddtln

- id-at-commonName=Onshthonese.vyrda-npeces.post

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 85.211.162[.]44:

- id-at-countryName=MY

- id-at-LocalityName=Kuala Lumpur

- id-at-organizationName=Ointavi Tagate Unltd.

- id-at-commonName=Ateei7thapom.statonrc.loan

Example Five: 2020-10-07-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap

Open 2020-10-07-Dridex-infection-traffic.pcap in Wireshark and use a basic web filter, as shown in Figure 23.

Checking through the domains, there is one non-Microsoft domain using HTTPS traffic that might be tied to the initial infection activity:

- newmg532.wordswideweb[.]com

Examine the post-infection Dridex C2 traffic. Use the following filter in Wireshark to look at the certificate issuer data for HTTPS traffic over the two IP addresses without domain names in the HTTPS traffic:

tls.handshake.type eq 11 and (ip.addr eq 177.87.70.3 or ip.addr eq 188.250.8.142)

After applying the filter, select the first frame, go to the frame details section and work your way to a list of lines that start with the term RDNSequence item as done in our first four examples.

The certificate issuer data follows the same pattern as our first four examples. Check the issuer data for both IP addresses and find the data listed below.

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 177.87.70[.]3:

- id-at-countryName=BS

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=Sshopedts Inccofrew

- id-at-LocalityName=Nassau

- id-at-organizationName=Mesureder S.p.a.

- id-at-commonName=avothelyop.thedai9neasysb.author

Certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic on 188.250.8[.]142:

- id-at-countryName=UA

- id-at-stateOrProvinceName=avandi0

- id-at-LocalityName=Kiev

- id-at-organizationName=Icccodiso Icloneedb Oyj

- id-at-organizationalUnitName=4Zenyfea

- id-at-commonName=rebydustat.tci

These five examples should give a good idea of what certificate issuer data for Dridex HTTPS C2 traffic looks like. These patterns differ from many other malware families, but they are somewhat similar to certificate issuer data from HTTPS C2 Qakbot network traffic.

However, with Qakbot, the stateOrProvinceName is always a two-letter value, and the LocalityName consists of random characters.

With Dridex, the stateOrProvinceName consists of random characters, and the LocalityName is the capital city of whatever country is used for the countryName.

Conclusion

This tutorial reviewed how to identify Dridex activity from a pcap with Dridex network traffic. We reviewed five recent pcaps of Dridex infections and found similarities in certificate issuer data from the post-infection C2 traffic. The certificate issuer data is key to identifying a Dridex infection, since these patterns appear unique to Dridex.

For more help with Wireshark, see our previous tutorials:

- Changing Your Column Display

- Display Filter Expressions

- Identifying Hosts and Users

- Exporting Objects from a Pcap

- Examining Trickbot Infections

- Examining Ursnif Infections

- Examining Qakbot Infections

- Decrypting HTTPS Traffic

Get updates from Unit 42

Get updates from Unit 42